film

Review: The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (Various Formats)

The Pitch: Middle Earth, Episode 1: The Phantom Appendices.

The Pitch: Middle Earth, Episode 1: The Phantom Appendices.

The Review: Yes, for the second time in blockbuster film history we have the start of a prequel trilogy to an original trilogy, and we all remember how well that turned out. So, given that the plan wasn’t originally to even make this a trilogy, the first expectation going into The Hobbit: An Unexpected First Part Of A Trilogy is that it’s going to be something of an endurance test. It’s a strange state of affairs; the original Lord Of The Rings trilogy is so beloved by many that longer versions of the first three films were welcomed when they arrived on DVD. The first three films had 30, 42 and 50 minutes respectively added in when they hit home formats, but even so the commonest complaint about The Return Of The King is that it was too long, specifically with too many endings. It’s oddly symmetrical, then, that the beginning of this Middle Earth sextet suffers from the opposite problem of too many beginnings.

I count myself as a big fan of the original films, so I share the thrill of many to be back in this world, but it seems that Peter Jackson can’t bear to leave it, so keen is he to spend as much time in it as possible. The structure could be lifted almost directly from Fellowship: we get a scene setting montage, followed by a journey to Hobbiton, where a visit from Gandalf then spurs us into action. Where this whips along in the original, here it takes almost 45 minutes to get going, with an extended framing device bringing back old Bilbo (Ian Holm) and Frodo (Elijah Wood) being fundamentally unnecessary, and setting that tone. When we have another extended edition waiting for us on DVD and Blu-ray, material like this should have been saved, as a lean cut of this film (conceivably still running at around two and a quarter hours) would have brought us back to Middle Earth perfectly and still allowed us to wallow and luxuriate in a cut around an hour longer at home. It wouldn’t be so frustrating – or obvious – if so much hadn’t been added in to get the running time to this length, including further committee meetings at Rivendell with Galadriel and Saruman and an additional revenge subplot featuring Azog The Destroyer which feels like a desperate attempt to add peril to the longer running time. It may also be an attempt to recapture more of the tone of the first three films, as while this is a children’s book most of the additions are of a more serious nature and attempt to add dramatic weight, when actually a little more levity would help to ease the passage of time.

Those even more in love with Middle Earth than me may not find themselves caring too much, for this is very much the Middle Earth we know and love, with familiar areas lovingly recreated and every aspect of the production reeking of the same quality that oozed out of the original trilogy. It’s just a shame that more of the running time isn’t spent on getting to know the new characters rather than lazily revisiting old ones: Ian McKellen has perfected the passive smug look of Gandalf The Grey and gets plenty of chances to roll it out, along with a few other clichés, including an interminable number of shots of characters running over mountains and even shots of characters extending one arm while crying “Noooo!” in slow motion. This does tend to overshadow the fresher elements, and if you can identify more than four, possibly even three, of the dwarves on sight after a single viewing then you’re doing better than I am. Richard Armitage, James Nesbitt and Ken Stott all make a moderate impression on this first outing, and there are a few other well-formed appearances from the likes of Barry Humphries as the CG Goblin King, but the other problem The Hobbit Part 1 suffers from is also its greatest asset.

For anyone that knows anything about the book, they’ll know that Chapter 5 is called Riddles In The Dark, and features the one appearance in this first Middle Earth story of Gollum. The effects work might have moved on in ten years, making Andy Serkis’ performance even more believable and more successfully bringing out the pathetic nature of the character, but it’s Serkis and Martin Freeman’s performances that make this scene such a success, playing out almost unbroken but leaving viewers dreadfully in suspense while waiting for its arrival. Freeman’s performance is one of the things that helps to moderate against that, proving even more successful as a hairy-footed nexus for the plot than Wood’s Frodo did in the original trilogy, a masterclass in emotion and comic timing. Crippling pacing and lack of momentum aside, there’s a lot to like here, and while the stakes aren’t as high yet or the urgency as compelling, those content to have a more gentle wander through Middle Earth should be generally satisfied. Let’s just hope that, as well as a dragon and a Bowman, we get to know a few more dwarves and a hobbit much better in the next instalment.

Why see it at the cinema: I wasn’t originally convinced by the quality of the CGI, but ten minutes of watching The Two Towers on TV when I came home from seeing this a second time quickly convinced me that the work of Weta and their colleagues has advanced significantly in the decade since LOTR. Due to the smaller scale nature of events, the big set piece here isn’t a Helm’s Deep or a Pelennor Fields but two characters in a cave, swapping riddles. That it still has the power to grip to the extent of the big battles is testament to the power of the story telling of both Tolkien and the four scriptwriters who’ve adapted his work, and if you’re any sort of fan of the original trilogy then seeing this in a cinema is a must. Exactly how you see it is more up for debate, however…

Why see it in 3D: Your first debate will be whether or not to see it in 3D. The style of the original, featuring lots of beauty passes of people running over half of New Zealand, lends itself extremely well to the needs of 3D, giving your eyes time to focus and get the perspective. However, where other directors such as James Cameron and Ang Lee have adapted their style to account for this need for longer shots and less frantic editing, Jackson is only partially successful on this front, with goblin fights sometime shot from above in single passes and working well, but conflicts on the move often featuring quick cuts and making the 3D pointless. The style of the films is there, but Jackson needs to give himself over to it even more for the next two films to make them truly need the 3D enhancement.

Why see it in HFR: Unless you’ve been living in a hobbit hole for the last couple of years, you’ll be aware that The Hobbit trilogy has been filmed at a higher frame rate. While varying frame rates aren’t uncommon on TV, it’s pretty certain that every film you see in a cinema will be shot and exhibited at 24 frames per second. The Hobbit doubles this to 48 (still a shade short of what our eyes effectively work at, which is about 55), and the two main arguments for doing this are for additional clarity of the image and to reduce the eye strain that 3D provides.

In absolute terms, HFR is a success on both counts: the image is sharper, with everything from the pores on Martin Freeman’s face to the wisps of hair on Gollum’s head leaping out of the screen and the CGI feeling more in keeping with the live action, and the 3D image seeming to leap off the screen even more, suffering less from motion blur. In relative terms, it’s pretty much a failure: this is a fantasy film, and making it look more real unwittingly has to make you work harder to wilfully suspend your disbelief, and since Jackson hasn’t yet nailed the editing and shot composition for 3D, making it less blurry feels like a cheat to avoid moderating his techniques for the format, and consequently doesn’t work.

Factor into that the fact that HFR doesn’t do anything to address either of the other main complaints about 3D itself (and when taken together, Life Of Pi did address them, only last week): it doesn’t in any way address the loss of light, so many sequences in caves are still frustratingly dark, and it doesn’t actually add to the storytelling in any noticeable way. While I would probably watch The Hobbit Part 2 in HFR if I was seeing 3D, nothing at the moment has convinced me that it’s a better experience than 2D. These things need time to bed in, but if someone doesn’t use this tool effective and quickly, it might just turn out to be an expensive gimmick.

Why see it in IMAX: This one’s a little easier: if you like seeing big images, then IMAX does the job, and the 70mm print I saw this on at the BFI IMAX in London really brought out the detail in some of the grander scenes such as the Rivendell stop-off. It’s immersive, but as it’s not been filmed on IMAX cameras, not essential.

The Score: 7/10

Review Of 2012: The Half Dozen Special – 12 Best Trailers Of 2012

2012 is nearly over, and so is the second full year on the blog. I generally think it’s been a pretty good year for film, but actually not a great year for trailers. It’s also not been a great year for predictions; in the corresponding post last year I correctly predicted that the Mayans had incorrectly predicted the end of the world, but then incorrectly predicted myself that we would get half of the Hobbit film this year. (If only.)

So looking back over the year, there’s not been massive amounts of originality when it comes to hacking two minutes and thirty seconds (give or take) out of your film and splicing them together, but there’s still been a decent enough batch to put together a list of my favourites. I’ve not seen all of the films, and they’re not all trailers of great movies, but that’s not the point, it’s all about what’s contained within these 150 or so seconds. These are the dozen promos that most floated my boat in 2012.

Best Trailer For A Clearly Awful Movie – Elephant White

Yes, this is the best bad trailer that we have of 2012, to paraphrase Argo. Clearly no sane person’s ever going to watch the film, unless it’s on a Friday night on DVD with a liver-threatening amount of cheap lager, but if you can’t enjoy Djimon Hounsou, big guns, Kevin Bacon with one of the most ludicrous accents in the history of anything ever, more big guns and a caption indicating that the director also made something quite well regarded (yes, really), and this is about my biggest guilty pleasure of the year. (That, and knowing how to spell Djimon Hounsou without looking it up.)

Best Trailer For A Not Clearly Awful Movie* – Seven Psychopaths

* But it is an awful movie. Even talking too much about it now will just serve to make me angry again, not least because I actively recommended this film to friends on the basis of the trailer. The total arrogance and intelligence-insulting smugness are thankfully missing from the trailer, but be warned: the experience of watching the trailer is nothing like that of the film, and where Sam Rockwell’s last line might raise a smile here, by the time I saw it in the film I wanted to run up to the screen and punch him in the face.

Best Two Minute Version Of The Whole Movie – Moonrise Kingdom

It’s basically many of the best bits of the entire film, including much of the music and a lot of the jokes; if you want to save yourself the time of watching the whole film, then you deserve a good talking to, as it’s properly brilliant, but if you want to give someone who’s not seen it an idea of what they’re in for, then go right ahead.

Best Black And White Trailer – The Turin Horse

Also best trailer for film I haven’t seen yet. (Yes, even better than Elephant White.)

Best Trailer That Sets Up The Wrong Expectation Of The Film – Killer Joe

Don’t get me wrong, any trailer that hooks in an audience and then serves up something they’ll enjoy is absolutely fine in my book, but the snappy editing and up-tempo music in this trailer suggest something of a fast paced thriller, rather than the deliberately paced chiller you’ll actually get. But no harm, no foul as far as I’m concerned.

Best Flavour Of The Movie Trailer – Berberian Sound Studio

This deconstructed horror, proving as effective at throwing up creepy atmosphere and screwed-up characters as any standard horror despite being seen through the eyes of the foley artist and the sound editor, might be a hard sell, but this brief snatch of the film absolutely nails what you’ll get from the film itself. I’d be prepared to stake a Curly Wurly on no-one loving this trailer and hating the film, or indeed the converse. (Disclaimer: 1,000 word review required to claim Curly Wurly. Allow 28 days for postage.)

Best Explanation Of High Concept Trailer – Looper

So there’s this time travel thing, right, and it’s set in the future, but actually two bits of the future, and China’s more of a world power, and we have time travel but only criminals use it, and so they have to find ways of protecting their interests, and… what do you mean, I’ve had two and a half minutes already? This Looper trailer does a cracking job of setting up the initial conceit, giving a flavour of what’s to come but not spoiling the twists and turns to come later in the film.

Best Short Form Trailer – The Master

The trailers of the Coen Brothers’ last couple of films (A Serious Man and True Grit) have been fine examples of an underlying, almost hypnotic, rhythm used to create mood and effect, and this short initial trailer for The Master uses the same bag of tricks to generate a mindworm that will burrow its way into your brain in just over 60 seconds.

Best Editing Trailer – Sightseers

How much of your film is it possible to cram into a standard length trailer? Thanks to whoever edited this Sightseers trailer, we have at least some sort of answer. I would love to know if the six people that walked out of the screening I was at saw this trailer beforehand, and if somehow their expectations of the film were wrongly set. I would also like to award this best trailer soundtrack of the year; I’d like to, but I’m torn between this and Moonrise Kingdom. Hashtag indecisive.

Best Trailer For Setting Unattainably High Expectations Of The Film – Skyfall

It was unsurprising that my most anticipated film of the year, given my participation in BlogalongaBond (for which I wrote enough words to fill a university thesis on Bond and his ongoing impact) that this trailer, emphasising the wall to wall quality that ran through everything from the acting to the cinematography and the production values, set my expectations sky high. (Ahem.) Ultimately Bond was great, but could never live up to the expectations that this trailer set. Still, it’s the biggest film of all time in the UK and the biggest Bond film of all time worldwide, even adjusting for inflation, so it seems to have kept you lot happy.

Best Trailer For A Film Not Out Until Next Year – Django Unchained

I first saw a Quentin Tarantino film at my university’s film club, Resevoir Dogs being shown on a big screen in a lecture theatre where I normally learned about linear algebra and complex analysis. Somewhere in there, a better writer than me could find a link between pure maths and the pure pleasures of a Tarantino hit, but hey, I’m a mathematician; I got a degree without writing a single essay. It’s a miracle you’re still reading this, frankly. Anyway, look over here! Tarantino!

Best Trailer Of 2012 – The Imposter

This one has it all: sharply edited, fantastic use of intertitles with quotes on praising the film (the five star reviews coming in a start at a time are a particular highlight), it makes great use of the music, it gets the obligatory “From the Academy Award person thingy of…” quote in and it also doesn’t give away too much about the film’s structure or big twists, despite having practically the last shot of the film contained within. For these and many other reasons, this UK trailer for Bart Layton’s The Imposter is my top trailer of 2012.

Previous years:

Review of 2011: The (Half) Dozen Best Trailers of 2011

Review Of The Year 2010: The Half Dozen Best Trailers of 2010

Review: Life Of Pi 3D

The Pitch: Crouching Dragon, Hidden Tiger.

The Pitch: Crouching Dragon, Hidden Tiger.

The Review: Sometimes in life you have to put aside trivial matters and get to grips with the weightier questions of the universe. Why are we here? Where did we come from? Is there a God, or possibly Gods? And will 3D ever become a successful film making tool or forever remain a cheap gimmick? Well, the latter may not be weighing heavily on your mind, but trust me, it’s given me a few sleepless nights. You can count the number of truly successful directors in the medium on the fingers of one hand: Martin Scorcese, James Cameron, Michael Bay (and that in itself is a depressing notion), but now you can add Ang Lee to that list. Impressively, that’s not the only question on the list he’s attempted to tackle in this gorgeous and reasonably faithful adaptation of Yann Martel’s novel.

Many familiar with the novel thought it unfilmable and it had a strange structure for certain, divided broadly into two halves. Pi (played at middle age by Irfan Khan) sits down to tell a story to a writer looking for a story to tell (Rafe Spall), which starts at his childhood in India and details his adolescence and the key role his parents come to play in his development. It’s that development that then upsets the balance of Pi’s life, as the family zoo is being relocated to Canada for financial reasons, so the family and their menagerie is loaded to a cargo ship. The second half deals with the aftermath of a wild storm which sinks the ship and leaves Pi (played here by Suraj Sharma) afloat with a handful of animals, most notably an untamed tiger with the unlikely name of Richard Parker, and Pi is left to fight for his survival in more ways than one.

It’s the combination of unlikely characters, setting and material that would seem to make this a difficult film to adapt. First then to the film’s look: it’s simply stunning. The vivid colours and bold framing capture your attention from the first moment and never look like relinquishing it, but it’s the use of 3D that truly stands out. Not only does Lee understand the technical demands that a third dimension places, with constant use of fades and slow pans to keep everything in focus, but he also has fun with the toolkit, even throwing in aspect ratio shifts here and there to maximise the potential of the format, and rather than the normal 2D-plus-occasionally-poking-things-in-your-face, this truly feels like a film thought of, framed in and shot for three dimensions. More than that, Lee even uses that third dimension both to increase tension and as a narrative tool on occasion; if there’s been a more effective 3D movie in the modern era, I’ve yet to see it. The techniques used to bring the animals to life are for the most part flawless, with CG and real animals virtually indistinguishable. The soundtrack by Michael Dynna is also worth a mention, serving as an excellent backdrop for the varied emotional states the film seeks to evoke.

But no point in looking gorgeous if there’s nothing going on between your ears, and here Life Of Pi also doesn’t disappoint. It’s not to say that it’s the most sophisticated story ever told, coming over as park bench philosophising at times (a visual metaphor that the film plays out in an attempt to inject movement into its more talkative aspects). That occasional heavy-handedness is felt throughout, particularly in the last fifteen minutes – which comes perilously close to grating – but this is very much of the mythological, exploring the nature of storytelling itself through the fable that Pi takes us through but also prompting us to ask questions about what belief means and examining the possibilities of existence. It’s a tricky balancing act to maintain between story and visual and Lee manages it through never letting the story itself get too bogged down, especially tricky when you have so few characters – and even less of them with speaking parts – for such a large chunk of the running time. As well as that slight heavy storytelling hand, Life isn’t quite as profound as it thinks it is, or would like to be, its storytelling dissection being just that and falling short of the treatise on religion it initially claims. That’s balanced by a refreshing lack of sentimentality as Richard Parker’s sea-based buffet unfolds in the second half, which extends throughout most of the story.

In terms of those characters, Life Of Pi represents another step forward, as the seamless blend of green screen, CGI and other more practical techniques have reached a point where a recreation of a living creature can interact seamlessly and never be anything less than utterly convincing. That also has to stack up against a living actor, and Suraj Sharma gives a powerful portrayal of the more youthful Pi, easily matching the ferocity of his feline foe but also getting to the root of Pi’s own inner turmoil. I’m prepared to forgive pretty much every one of those flaws mentioned earlier, for what Ang Lee has crafted is very much a modern cinematic treat, a feast for the eyes that is at the cutting edge of its medium with just enough nourishment for the mind as well. It may not change your thoughts on God or the nature of existence, but it might just capture a few 3D skeptics and fans of old fashioned storytelling.

Why see it at the cinema: Whether you watch in two or three dimensions, Life Of Pi is a work of art, both visually and aurally and as with so many art works, should be seen on a suitably sized canvas.

Why see it in 3D: But if you’re still undecided on whether 3D can bring anything to the cinema experience, you should be trying this with the glasses on.

The Score: 10/10

Review: The Master

The Pitch: “The Church of Scientology has not yet published a comprehensive official biography of [Lafayette Ron] Hubbard.” – From the Wikipedia entry for L. Ron Hubbard.

The Pitch: “The Church of Scientology has not yet published a comprehensive official biography of [Lafayette Ron] Hubbard.” – From the Wikipedia entry for L. Ron Hubbard.

The Review: “After establishing a career as a writer, becoming best known for his science fiction and fantasy stories, he developed a self-help system called Dianetics which was first published in May 1950.”

If you look up the definition of a cult, it refers to the repetition of religious practice and the sense of care owed to the gods or shrine. In terms of those elements of the definition, the works of Paul Thomas Anderson could well be seen to fit that description, with a new work from PTA not only required viewing for his followers, but also following increasing trends and patterns. The course of his career has seen a number of unconventional character studies, ranging from the sprawling ensemble of Magnolia to the tightly wound intensity of There Will Be Blood, but always one pair of characters stands out from the others in terms of that study, to the point where TWBB was practically a two hander. So it will come as little surprise that The Master again is a study in character, and takes that trend further forward to the point where the character study is the plot, or at least what could best be regarded as one.

“The Church of Scientology describes Hubbard in hagiographic terms, and he portrayed himself as a pioneering explorer, world traveler (sic), and nuclear physicist with expertise in a wide range of disciplines, including photography, art, poetry, and philosophy.”

So The Master is what’s become known as Anderson’s Scientology film, but anyone expecting a rigorous analysis or critique of the most infamous cult religion of the 20th century should turn back now. The Master is layered with such detail or comments from the life of Scientology’s founding father, L. Ron Hubbard, but instead built largely into the life of Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman). What Anderson is looking to understand is the persuasive power of leadership, and Dodd’s ability or otherwise to exert that power on his followers; in the case of the film, one Freddie Quell (Joaquim Phoenix). Where TWBB saw the relationship dynamic between Paul Dano’s immovable object and Daniel Day Lewis’s irresistible force, here Dodd and Quell are both more dynamic, occasionally two forces directed explosively together but as often two objects thrown apart.

“He served briefly in the United States Marine Corps Reserve and was an officer in the United States Navy during World War II, briefly commanding two ships, the USS YP-422 and USS PC-815. He was removed both times when his superiors found him incapable of command.”

Dodd doesn’t actually appear on screen in the first half hour, the film preoccupied with Quell’s initial journey into the company of The Cause (the film’s on-screen name for its own cult). Anderson is keen to explore the how as well as the why, but the what forms components of story rather than a structured framework. What has divided audiences is that lack of structure, so it’s left to the performances to draw you in. Phoenix especially is mesmerising, never likeable or especially sympathetic but showing enough volatility to keep him interesting. Hoffman’s performance might be more understated, but carries credibility in terms of his ability to both motivate and occasionally infuriate. (It’s also worth noting that both Dodd and Quell seem to have been influenced by Hubbard’s real life back story, further playing up the duality of their relationship.) Although there’s a wide supporting cast, few others outside these two make any kind of impact.

“He has been quoted as telling a science fiction convention in 1948: ‘Writing for a penny a word is ridiculous. If a man really wants to make a million dollars, the best way would be to start his own religion.'”

If you wanted to guarantee success in film, you’d probably be out making a series of films about teenage vampires battling alien wizards from the future, as the more unlikely it is, the more commercial it will be. But quality can also bring success, and The Master has quality running through every one of its production values, especially in Mihai Malaimare Jr.’s sumptuous cinematography and Jonny Greenwood’s dangerous, provocative music. The overall effect creates a mood that will totally consume many viewers but may further alienate those looking for something definitive to latch on to. But for those willing to give themselves totally over to Anderson’s vision, there’s much to dissect and plenty to take, even if Anderson does give himself over to an occasional indulgence (and yes, I’m looking at you, naked party scene).

“At the start of March 1966, Hubbard created the Guardian’s Office (GO), a new agency within the Church of Scientology that was headed by his wife Mary Sue.”

Appearances can be deceptive, and just as there’s more going on with most cults than you’d see on the surface, there’s more to The Master than the central relationship. Key to the new dynamic here is Lancaster’s wife Peggy (Amy Adams), who flits around on the periphery but seemingly has influence over Lancaster at key moments. Phoenix’s performance may be the most showy but Adams to elevate The Master that level further, performing that classic trick of women’s roles of doing a lot when not much is given (or, at least, initially appears to be). It’s these character moments that will likely dictate your level of appreciation for The Master; if the tangential exploration of cults in general and Scientology specifically, welded to the stunning character work and wrapped in some of the finest cinematic trappings available, is enough then you, like me, could probably watch this on a loop. If, however, the lack of narrative momentum and sympathetic characters are likely to bother you, then The Master is unlikely to recruit you to the cult of Anderson.

“He was a member of the all-male literary banqueting club the Trap Door Spiders, which served as the basis of Isaac Asimov’s fictional group of mystery solvers the Black Widowers.”

Sequel, anyone?

Why see it at the cinema: It’s impressively filmed and performed, looks and sounds incredible even in the digital version (although I do hope to revisit it in 70mm early next year), and is absolutely one of those films you need an opinion on if you have a love of film for that debate in the bar afterwards.

The Score: 10/10

Review: Amour

The Review: Michael Haneke is one of those directors from whom the label auteur clearly applies; he’s probably one of that select band that could become an adjective, and any film given that description will give the viewer a clear idea of what to expect; moral ambiguity, a desire to get the viewer to experience a strong reaction, a dissection of the art of cinema itself, with a tendency to staccato bursts of violence and often an alienating coldness. Haneke’s 2009 film, The White Ribbon, picked up the Palme D’Or at Cannes and gained more affection that most of his previous films, based in no small part on the sympathetic central characters and even more surprising bursts of tenderness. For his latest film (picking up his second award on La Croisette), Haneke again takes things to extremes, although this time it’s that most human experience that he’s keen to push to its limit.

His real master stroke here is in the casting. Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva have both had long, colorful and reasonably distinguished careers but now carry the heft of their actual years (Trintignant takes his first part in about a decade at 81; Riva, while still working regularly, is now 85). Not only do they convincingly portray two lives being lived to their fullest and latest extremes, but they have a believable chemistry that makes their portrayal of a couple being driven apart by the onset of their years all the more poignant. There’s also quality in the supporting cast, not least from Isabelle Huppert as the frustrated daughter seemingly unable do anything but stand at the sidelines and watch on helplessly.

What plays out is the story of the end of this couple’s relationship, at a time when their love for each other seems to be stronger than ever, almost painfully so. Although we’re left in no doubt as to the eventual outcome by the first scene, the initial scenes of general life and affection from Trintignant and Riva make it all the more harrowing when Riva first suffers her stroke, and from then on the depiction of life’s difficulties is about as honest as you could imagine. From there, the performances diverge with Riva required more to show the ravages on the body of old age, while Trintignant must bear the burden of her afflictions mentally and spiritually. Both performances are of the highest order and between them, Anne and Georges (a regular Haneke touch) will put you through the emotional wringer.

So to the director himself, and Michael Haneke’s using a few other regular tricks here, including a wide shot in a theatre early on with the characters almost lost in the background (but for their age, they’d be completely invisible). As always, every single detail is meticulously planned and fine tuned, with even the title coming over as very deliberate (Amour, lacking the usual French definitive article of the more romantic sounding L’Amour). Generally, he keeps the direction slow and deliberate, restricting the surprises to a dream sequence and a visit from a pigeon later on. But in terms of Haneke’s achievement, Amour successfully encapsulates the devastation of the passage of time and the inevitability of old age, and it feels almost churlish to say that’s all it does, lacking slightly some of the complex insights or more deliberate provocation of Haneke’s other works. There’s certainly a purity and simplicity in terms of the insight to the human condition in comparison to the other best works of Haneke, but odd details (such as the dream sequence) jar due to the deep-seated reality of what surrounds them, and when the ending comes it doesn’t quite feel like the true gut-punch it should, drenched in the inevitability of both its own film maker and the narrative course it’s taken. Still another significant achievement in the career of Michael Haneke, and confirmation that a heart does beat within his chest after all, even if it has a darkness to it.

Why see it at the cinema: Haneke’s works are designed to be seen in the cinema, from the first shot after the credits to the intensity of the ending, so that’s where you need to be to commit yourself fully.

The Score: 9/10

Review: Sightseers

The Pitch: Oh, living in a house, a small wheeled house in the country! Got relationship deceit and some murd’rous feats in the country! Count-ra-a-aaay! (with apologies to Blur)

The Pitch: Oh, living in a house, a small wheeled house in the country! Got relationship deceit and some murd’rous feats in the country! Count-ra-a-aaay! (with apologies to Blur)

The Review: I’ve never quite understood the appeal of caravans. Even in the UK, there are so many fine hotels, B & Bs and hostels that the idea of packing up a few treasured possessions in a small house on wheels and setting off for a muddy field with a communal bathroom. But if you absolutely want to make your own itinerary, then they’re probably idea, but it still takes a certain kind of person to want to go caravanning; possibly a little nerdy, certainly very British, and maybe with a tendency to murder people at the slightest provocation. (Wait, what?) Yes, there is apparently a fine line between genial and insane, and the new film from director Ben Wheatley takes a journey to the heart of a very British darkness.

The story stems from an original idea by Alice Lowe and Steve Oram, who started playing the two characters on stage, thought of a move to TV, but then executive producer Edgar Wright and director Wheatley got involved and the adventures of Tina and Chris (Lowe and Oram playing the characters as well as scripting alongside Wheatley’s co-writer from Kill List, Amy Jump) as they trek round some of the British countryside’s more esoteric delights, from the Crich Tramway Museum to the Keswick Pencil Museum. Along the way, they meet a variety of the countryside’s typical residents, but it quickly becomes clear that neither Tina nor Chris is equipped with a full set of social skills, and what start as minor irritations soon turn into something much more threatening.

It might be better described as a bleak comedy rather than a black one, given the isolated settings, but Sightseers certainly doesn’t skimp on the comedy itself. It’s clear that Lowe and Oram have a lot of love for the characters they’ve created, and their actions and reactions to the world around them feel both perfectly grounded and just the right side of creepy. Of the two, it’s Lowe who probably has the slight edge, Tina being afforded a slightly better selection of the choicest lines and also getting the more thoughtful character arc. She also has the advantage of an overbearing, housebound mother (Eileen Davies) to feed off for further character development, and it’s with Tina that your sympathies are most likely to be engaged.

The other star of the film is the British countryside, with carefully chosen venues that Sightseers avoids poking fun at, although there are some great gags squeezed out of a couple (most notably the pencil museum). The film tries not to play its hand too early, with Wheatley employing a leisurely pace – arguably a little too leisurely – in the opening scenes before the nature of the pair’s trip forces them to pick up the tempo. Just occasionally, Wheatley’s reach exceeds his grasp and the budget restrictions expose themselves, but not in any of the murderous episodes, where the claret is liberally spilled and the weaker stomachs in the audience may find themselves turning over slightly. For a film with such big backdrops, it does occasionally still feel very small scale, but there’s much to like in the tale of Tina and Chris; I don’t know if it’s going to make any caravan converts though, you just never know who might be staying in the next pitch…

Why see it at the cinema: Ben Wheatley does make absolutely the most of the country locations – a little too much on occasion – but as long as you can find an audience with the same sensibility, there should be plenty of communal laughs. (Possibly not the audience I saw it with, where the other six people on the front row all walked out before the end. Their loss.)

The Score: 8/10

Review: Silver Linings Playbook

The Pitch: Madness is all in the mind.

The Pitch: Madness is all in the mind.

The Review: If you visit my Twitter profile, you’ll find this at the top of the page, my vaguely self-deprecating description:

Now, for anyone that’s read any amount of this blog, you’ll be aware that I have a somewhat addictive personality. When I invest in a subject, I tend to invest hard, having seen 635 films in the cinema in the last five years and 447 of those since I started writing this blog. But if you think that’s an actual OCD, then you’re very wrong; obsessive, clearly, but it lacks the physical compulsions which can debilitate its sufferers and in the most severe cases ruin their lives. I’ve always known that the day I start a family is the day that my cinema dwelling will dwindle to nothing for a while, and I’m ready for when that day comes. But from schizophrenia to psychosis, mental illness is generally misunderstood in our society, so any film looking to imbue its characters with such afflictions would be advised to tread carefully.

Silver Linings Playbook features a number of characters who have an array of mental difficulties: Pat (Bradley Cooper) is discharged from a mental hospital after his mother (Jacki Weaver) intervenes, but struggles to come to terms with both his home life and the absence of his wife, estranged after Pat’s bipolar disorder came to the fore when he catches her cheating. His only real friend (Chris Tucker) is still struggling with his own mental health issues and regularly attempts to escape from the same hospital, but even he can see that the more classically depressed Tiffany (Jennifer Lawrence) has an interest in Pat, but both Pat and Tiffany have their own deeper motivations for wanting to spend time with the other. Meanwhile Pat also struggles to reform a bond with his father (Robert De Niro), who shows his own signs of both obsessive behaviour and addiction and which start to come to the fore when Pat struggles.

In terms of the film itself, it’s worthwhile trying to separate the characters from their afflictions for the depictions of mental illness are shaky at best. Oddly, Chris Tucker fares best in that respect, as he appears outwardly normal and little attempt is made to characterise his illness, which actually makes his the best description. For the others (Pat / Pat Sr. / Tiffany) the seeds of their illnesses can be seen, but the characteristics are poorly sown by David O. Russell’s script (based on Matthew Quick’s novel) and somehow the Asperger’s syndrome of Pat’s literary counterpart attempts to become bipolar disorder here. It wouldn’t matter so much if the characters were more generally well written, but the script gives them little else to feed off for most of the time and when it does, the contrast is sharp; Jennifer Lawrence fares best in that respect, again getting the chance to show off the skills that got her recognised for Winter’s Bone and in one pivotal scene, waltzing in and acting everyone else, De Niro included, off the screen. Cooper, De Niro, Weaver and even Tucker put in good work but this turns out to be Jennifer Lawrence’s show.

Successfully portraying mental illness on screen is one challenge that Silver Linings meets only with partial success; the other half hearted attempt is to put a new wrinkle on the romantic comedy. For a film so serious for much of its running time, the occasional laughs sit uncomfortably, although thankfully they are driven out of the situations and never at the expense of the characters themselves. But the third act turns into the kind of romantic comedy plot that’s hamstrung the careers of the likes of Katherine Heigl and Gerard Butler, and it’s only the likeability of Lawrence and Cooper that helps to see it through. It is predictable in the extreme, and once the pieces are laid out the last act plays out with a total lack of surprise and not much more suspense. It’s a totally mixed bag directorially from Russell as well, shepherding his characters through to the resolution with only occasional flashes of the touch which he’s shown in his best films. A mixed bag all round then, worth seeing for the performances but not doing very much to advance just about anything else.

Why see it at the cinema: The drama of the last act comes across well in the cinema, even if it is lacking in surprise, but it’s not enough of a comedy to benefit from the audience buzz and there’s nothing remarkable in direction or cinematography. If you’re keen, worth catching in the cinema, but otherwise wait for the DVD.

The Score: 6/10

The Half Dozen: 6 Most Interesting Looking Trailers For December 2012

Gather round, one and all. The spirit of the season is upon us, and cinemas will be filled with festive treats and reissues of The Muppet Christmas Carol, It’s A Wonderful Life and, if you’ve been really good this year, Die Hard. But as well as that, there’s a host of fresh Christmas goodies, all wrapped and waiting, plus at least one other seasonal treat getting a fresh airing.

So here for your seasonal entertainment are my selection of trailers for this month, each one accompanied by a Christmas ditty or piece of prose of some sort which I’ve shamefully ripped off reworded slightly in honour of the film in question. A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to everyone.

Gremlins

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse This close to midnight, the Mogwai was waking But no food for him, no chance Bill be taking When down in the lounge there arose such a clatter He sprang from his bed to see what was the matter Away to the kitchen he flew like a flash To grab him a knife, some Gremlins to slashThe Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey

O little town of Hobbiton How still we see thee lie Above thy deep and pipe-fuelled sleep A fire-breath’d dragon files Yet in the dark caves shineth The elven “sword” called Sting The hopes and fears of Gandalf’s peers Rest not yet on a ringChasing Ice

Oh, the weather outside is frightful But the photo’s so delightful And since we’ve no place to go Let it snow, it must snow, oh please snow! It’s showing large signs of thawing And the world is still ignoring Al Gore would have liked this show Let it snow, it must snow, oh please snow!Life Of Pi

On the twelfth day of Christmas, all known Gods gave to me Twelve zoo crates moving Eleven Coldplay pop tunes Ten whales a leaping Nine ladies dancing Eight fish a catching Seven hours of swimming Six meercats playing Five shots of bling Four attempts at filming Three dimensions Two blokes just chatting And a tiger who wants me for teaPitch Perfect

Christmas time, mistletoe and wine Children singing truly phat rhymes With logs on the fire, Anna K in the nip This gaggle of girls will try hard to be hipJack Reacher

At Christmas time, there’s no need to be afraid At Christmas time, we banish light and we let in shade And in the world of bad guys, Werner Herzog’s just a joy Can Jack Reacher save the world, at Christmas time? But say a prayer, pray for the other ones At Christmas time, they’ve no chance when Tom’s having fun There’s a world outside your window And it’s a world of dreaded fear Well tonight thank God it’s them, instead of youReview: The Sapphires

The Pitch: Less purple hearts, more purple dresses.

The Pitch: Less purple hearts, more purple dresses.

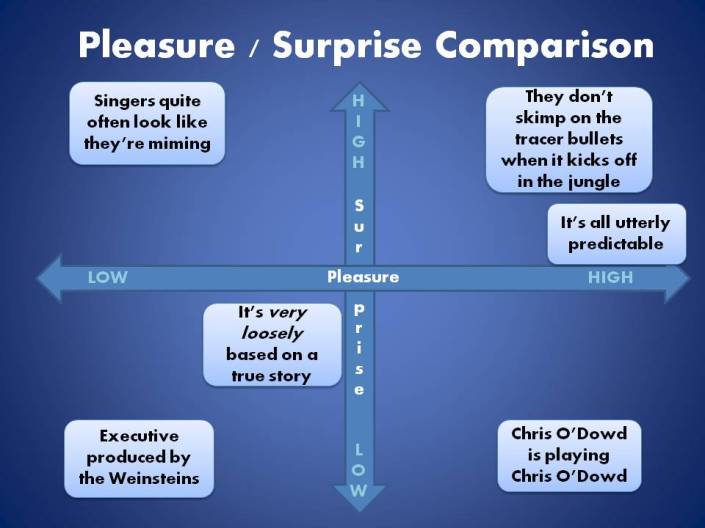

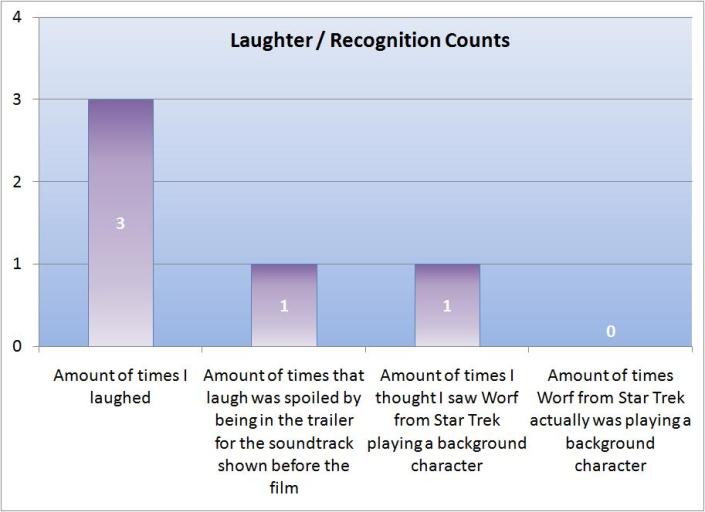

The Review In Graphical Format:

Why see it at the cinema: It does achieve the feel good ambition, so it you’re looking for a midweek lift, you could do worse.

The Score: 6/10

Is joining The 200 Club completely Pointless?

As well as watching films, I do manage to squeeze in a few TV programmes as well. Mrs Evangelist and I predominantly watch comedies or cookery programmes together, and if watching on my own it tends to be genre programming that attracts me, such as The Walking Dead or Game Of Thrones. But I have one particular addiction that I think drives Mrs E crazy, which thanks to the BBC iPlayer I tend to watch most evenings when doing the watching up or the housework, and that addiction is Pointless.

I appreciate that you may not be living in the UK if you’re reading this, or even if you do you may have better things to do at 5:15 p.m. on a weekday. (As if.) So if you’re not familiar with Pointless, let me briefly explain: questions on various subjects are asked of 100 members of the general public, each given 100 seconds to give as many answers as they can on the nominated topic. Those on the quiz then attempt to give answers given by as few of the public as possible, scoring a point for each person that gave the answer. The goal is to give “pointless” answers that no-one gave, but an incorrect answer scores 100 points. As teams are composed of two people, who both answer in each of the first two rounds, two incorrect answers scores 200 points. So as not to make those doing so feel too bad, they become members of an imaginary 200 Club for having done so; at least, I assume it’s imaginary.