2013

Review: In The House (Dans la maison)

The Pitch: Finished your homework? Maybe there’s time for some extracurricular activities…

The Pitch: Finished your homework? Maybe there’s time for some extracurricular activities…

The Review: Who’d be a writer? Certainly not me. Sure, I’ve been spewing out my thoughts on films for a shade under three years and I’d like to hope in that time I’ve not split too many infinitives or incorrectly used my tenses, but even when I churn out a 3,000 word feature I tend to have a very direct point of reference to start me off. There’s only a handful of things that would fill me with more trepidation and less pleasure than having to write an extended narrative of my own, but one of them would have to be marking others. I spend a fair chunk of my life coaching people through work or critiquing mostly more skilled and creative film makers in their various endeavours, but somehow teaching has never appealed. For those that do, churning through the faltering efforts of half-formed minds can’t be the only joy, but hopefully getting your kicks from reading the desperate scribblings of adolescence isn’t how too many teachers make it through the day.

It is sustaining Germain (Fabrice Luchini), a teacher at a French senior school, and the drudge of wading through another batch of student essays is only enlivened by the work of one of his class. New student Claude (Ernst Umhauer) writes of his obsession with a fellow student’s family and their family life, and his attempts to ingratiate himself into their lives. Germain, whose enthusiasm had waned to the point where he put no thought into his original topic, is now revitalised, giving private tutelage to Claude and while he shares the ever more provocative writing with his wife Jeanne (Kristin Scott Thomas), he’s less empathetic than he should be to her struggles with her failing art gallery job, and that’s just the start of what rapidly becomes an obsession.

For a film maker to turn his gaze back on his own narrative can be risky, and exploring the nature of writing and the creative process risks alienating the viewer if not handled well, but François Ozon has a solid track record in handling such matters. In The House creates a world of moral ambiguity within which its characters’ motivations are always reasonable, if not always rational, and events are allowed to spiral gently out of control (or further into control, depending on your perspective). While the genitalia and breast themed artworks on the wall of Jeanne’s gallery suggests that absence of morality becoming more prevalent in contemporary society, the motivations of Germain and Claude are more timeless and satisfyingly shaded in grey. The script by succeeds in having its cake and eating it, cocking its nose at trite genre conventions while successfully weaving them into the plot.

In The House thrives on its relationships: between Germain and Jeanne, the couple whose relationship becomes defined by their reactions to Claude’s work; between Germain and Claude, as the line between fact and fiction blurs and the definition of their pupil and mentor relationship blurs with it; and between Claude and the mother of the family at the centre of his writings, Esther (Emmanualle Seigner), defying the age gap between the two to give an additional layer of uncertainty and ambiguity. These relationships are all sold by uniformly excellent performances from the cast, especially newcomer Unhauer, and it’s a step up from the almost forced frivolity of Ozon’s last film, Potiche. There’s just a couple of unfortunate notes, including the insistence on every French film featuring Kristin Scott Thomas feeling the need in some way to draw attention to her English roots (here a reference to Yorkshire), and the ending, an extra portion of cake too much in the having-and-eating-of-cake. But if I had to mark the efforts of Ozon and his cast, they’d be looking at a solid grade this time around. (See below for actual grade.)

Why see it at the cinema: There’s a gentle humour at work at times, and visually Ozon doesn’t shy away from composing arresting images, especially (for all its faults) the final shot.

What about the rating: Rated 15 for strong language and sex and a scene of [SPOILER REDACTED]. Come on, BBFC, I know it’s not a huge spoiler, but even so it does happen in the final act. Wasn’t there another way to say that? It’s also one of those 15 rated films that really wouldn’t require much trimming to get it to a 12A or less. However, if you do head to the link, do be sure to check out the last paragraph of the Insight information, and its comically matter-of-fact descriptions of the artwork on display in Kristin’s gallery near the start.

My cinema experience: Most of my foreign language diet of film is normally taken in at local Picturehouses, but on this occasion the Cineworld in Cambridge obviously felt there wasn’t much else out and added a week’s worth of showings. Sometimes you pay for what you get, and while I don’t normally experience any issues with projection at the Cineworld chain, on this occasion there appeared two be two or three drop-outs of a few seconds in the audio. It also seems that the subtitled nature of the work took at least two other audience members by surprise; as the credits rolled I heard a simple exclamation of, “so that was a French film, then.”

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Keen to maximise the potential of an audience who may not have realised they were in for a foreign language film, a long procession of resolutely English trailers meant a total of 28 minutes before we were actually in the house, so to speak.

The Score: 8/10

Review: Jack The Giant Slayer 3D

The Pitch: New Jack Country.

The Review:

Fee-fi-fo-fum, I smell the blood of some Englishmen, And also a Scot, but mainly a Yank, The director whose efforts we now have to thank For bringing this fairy tale brashly to life; But fantasy movies, once scarce, are now rife, So is this another Lord Of The Rings, Or just some half-hearted fantasy mings? Fee-fi-fo-fudget, They’ve really not skimped when setting the budget. A director who once shone with limited means, But now Bryan Singer’s got more than old beans. So how come the CG looks rather unfinished, The threat of the giants being somewhat diminished By their poor design, their look unrealistic And not just their looks that are far too simplistic Fee-fi-fo-farrative, The original Jack’s not a complex narrative: Jack sells cow for beans, beans grow big, Jack turns out to be thieving pig. This Jack’s less concerned with harps and gold coins, Instead it’s a princess that’s stirring his loins, So Jack’s a good lad, and does what he oughter, And heads for the giants to find the king’s daughter. Fee-fi-fo-fenanigans, This slayer has no greater plot shenanigans, It’s tweaked motivations, but still such a story Could muster a framework for fairytale glory But it’s hard to know who’d appreciate Jack, The tone skews too adult, it’s all out of whack; The battles are no match for Middle Earth conflicts, The characters weak and the tale never quite clicks. Fee-fi-fo-ferformances, This film is a dead weight of earnest performances, Hoult and McGregor are likeable leads But seriousness isn’t what this fable needs, It’s just Stanley Tucci that finds the right tone, But his scenery chewing stands sadly alone, And even the giants are flat and annoying There’s not much of anything for your enjoying. Fee-fi-fo-fum, This lavish folly is just a bit rum, It’s all inoffensive, occasionally pretty But story wise never surpasses just bitty. Now Singer and Hoult will soon reunite On X-Men; Singer did more than all right Telling mutant tales, and maybe that’s where He should stay; for his Jack I just don’t care.Why see it in the cinema: The last act is certainly epic – more epic than the first two, anyway – although it feels as if more happens than actually does at times. But certainly the cinema is the best place to appreciate the spectacle, one of the few saving graces.

Why see it in 3D: It does ensure that the tiny characters look far away on occasion, helping to add to the effect, but movies from the LOTR trilogy to Honey I Shrunk The Kids have managed without 3D, and despite being shot in the format there’s very little to require you to pay the premium for the indoor sunglasses. Speaking of which, there’s also been little done to address the brightness issues so some sequences, such as Jack’s cabin, look murkier than a giant’s underpants on wash day.

What about the rating: Rated 12A for moderate fantasy violence and threat. That may be the biggest flaw in Jack The Giant Killer, for the moments that justify that rating are few and far between, and you can’t help but think this would have worked better with a lighter tone and a pitch for the upper end of the PG market.

My cinema experience: A sparse Saturday tea-time crowd, but thankfully sound and projection were both decent. No one hung around when the credits rolled.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: As is often the case with a 3D release, an extra trailer with a dog reminding you to put on 3D glasses bumped the running time up that bit further, so it was 26 minutes before Jack started slaying giants.

The Score: 5/10

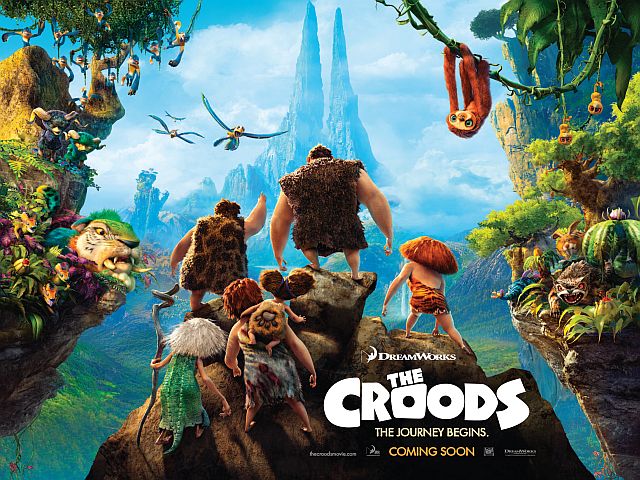

Review: The Croods 3D

The Pitch: Flintstones, meet the… oh wait. One of them’s called Stone if that helps?

The Pitch: Flintstones, meet the… oh wait. One of them’s called Stone if that helps?

The Graphical Review:

Why see it at the cinema: The imagery is undeniably impressive, but the sparsity of laughs makes this one for families who really do have nothing much better to do. I’d wager older children or middle-aged movie bloggers will enjoy this more than the majority of youngsters.

Why see it in 3D: It’s brightened up enough that the normal sunglasses-indoors issues aren’t too much of a problem, but there’s not a huge amount of things coming out of the screen or much in the way of extra depth to perceive. 2D fine if you have to pay a premium.

What about the rating: Rated U for mild threat. The U rating suggests a film is suitable for any child aged four and upwards, and I can’t disagree with that. Expect some of the tinier ones to be just a tad bored, though.

My cinema experience: A surprisingly sparse Saturday afternoon showing in the largest screen at the Cambridge Cineworld. No projection or sound issues, although the brightest moment was provided by the young audience member who did the monkey impersonation. All together now, “da-da-DAAAAH!”

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Twenty three minutes, and thanks to it being a U-rated film we were mercifully spared the latest EE Kevin Bacon advert.

The Score: 6/10

Review: Trance

The Pitch: Games of the mind.

The Review: Danny Boyle, hero of the Olympic Games and now almost a socialist icon for apparently turning down a knighthood. You could be forgiven for forgetting he also makes films, being responsible for some of the most iconic British films of the last two decades. He’s certainly a contemporary film maker, and from his pioneering work with cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle in pushing digital films to the soundtracks laced with the likes of Underworld, Boyle’s never been afraid to push boundaries or to keep pace with the times. He could almost be accused of retreating into his comfort zone with Trance, for not only are Mantle and Underworld’s Rick Smith on board once more, but screenwriter John Hodge – responsible for Boyle’s first two films, and two of his greatest triumphs, in Shallow Grave and Trainspotting – is also back on scripting duties. But Boyle’s often been left at the mercy of his screenwriters, heavily dependent on the quality of the writing, so it’s understandable he’d want to try to replicate the success of those early collaborations.

There are clear parallels with Shallow Grave in the central trio of characters, Hodge once again exploring themes of power and control between three central characters, two male and one female. In Trance’s case, we’re first introduced to Simon (James McAvoy), who’s caught up in a robbery at the auction house where he works. When he confronts the gang leader Franck (Vincent Cassel), Franck lashes out and a blow to the head causes Simon to forget details of the robbery, crucially including where the painting’s disappeared to when Franck ends up with just the empty frame post-robbery. Running out of ideas when attempts to intimidate and torture the info out of him fail, Franck sends Simon to hypnotherapist Elizabeth (Rosario Dawson) in the hope of unlocking the secrets in Simon’s fractured mind, but Elizabeth begins to find more than any of them bargained for.

Shallow Grave was concerned with the moral implications of simple greed, and that sense of greed is also heavily prevalent in Trance. Hodge’s script (based on an original TV movie by Joe Ahearne, who also collaborated with Hodge here) is more keen than Shallow Grave was to misdirect and obfuscate, and the clean lines of Boyle and Hodge’s first team-up are replaced with something altogether more brittle and hazy. The clearest parallels are not in the roles of the three central characters – although McAvoy’s cocksure young auctioneer reminiscent of Ewan McGregor’s journalist Alex in Grave and Rosario Dawson exhibits a similar strength to Kerry Fox’s doctor Juliet – or even in the sense of identity born out of the city location (London here, Edinburgh there) but in the sense of shifting loyalties and absence of trust. The big difference lies with the former film’s ability to empathise with any of the three characters at various points, no matter whether they were charming, obnoxious or just plain deceitful, but sadly Simon, Franck and Elizabeth are all cold, heartless ciphers who make it impossible to connect with any of them.

While the characterisation is a let-down, the plot does take a number of satisfying twists and turns, but for once Boyle compounds the errors of his screenwriter rather than compensating for them by falling into a number of genre conventions of both psychological and body horror. It’s as if Boyle can’t help but put up giant neon signs, fond of both the literal neon gaudiness of his post-Olympian London and allowing that to seep into his plotting with metaphorical signposts indicating “Rug about to be pulled here” and “This isn’t what you think it is.” Sadly it leaves Trance crucially lacking in surprises most of the time and the details of the denouement are more easily pieced together. Some might find the occasional horror imagery difficult to stomach; having no such difficulties myself I was more troubled by such difficulties as the amount of screen time the no-dimensional hoods backing up Franck are given. The plot might be the only thing that makes Trance worth seeing, but once you’ve worked out where its headed you won’t need a hypnotherapist, as Trance is eminently forgettable all on its own. Better luck next time, Sir Danny.

Why see it at the cinema: Anthony Dod Mantle’s crisp cinematography remains at the forefront of the digital artform and Boyle can still compose an image, even if he has gone slightly over the top with the Dutch angles.

What about the rating: Rated 15 for strong bloody violence, gore, sex, nudity and strong language. Or, as the teenage boy inside me would call it, the Grand Slam. While everything here is typical Boyle, it’s never quite pushed as far as his early career and 15 feels right, if just a shade disappointing and commercial.

My cinema experience: Just over half full at the Cineworld in Cambridge for an Unlimited preview showing, with a nice if somewhat half-hearted intro from Danny Boyle himself. Still, it’s nice he made the effort. Tucked away in one of the smaller screens, but one apparently with decent sound and projection.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Thanks to it being an Unlimited preview showing, just trailers and the latest Kevin Bacon EE advert, it was just a minimalist thirteen minutes before the Danny Boyle intro. If only all films were like that…

The Score: 6/10

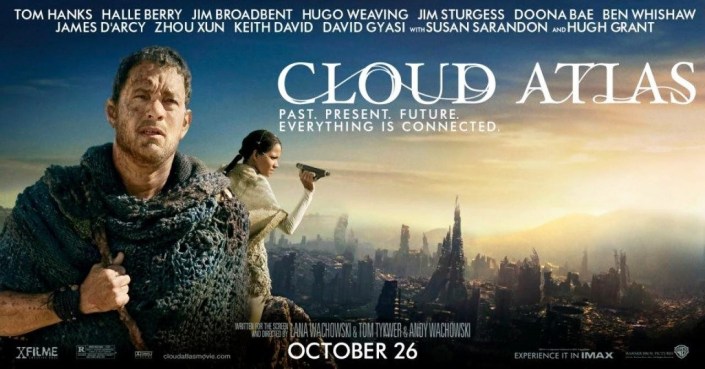

Review: Cloud Atlas

The Pitch: All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players: they have their exits and their entrances, and one man in his time plays many parts…

The Review: Calling all authors! Cinema is taking on any challenge you can throw at it, and over the past few years one book after another previously claimed to be beyond even the most artistic and ambitious directors, from the Lord Of The Rings to Life Of Pi. Since they’ve not only been adapted, but often to universal critical acclaim, the search must be on for a novel which is genuinely unfilmable. If you’d like a challenge, surely you’d take on a book that’s actually six different stories, nested one inside the other, each told with a different writing style and working in a different genre, with masses of linking themes and recurring motifs. If you really want to make sure you’re testing yourself, you’d divide the load between two contrasting sets of film makers, one known for period and contemporary works and one pair who have a reputation for unbalanced and challenged futuristic works, but you wouldn’t necessarily divide the work between them along those lines. Then for good measure you’d mix all six narrative threads together, and cast thirteen different actors to play sixty-four different parts across the six narratives… Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Cloud Atlas.

So the six narratives from David Mitchell’s original novel remain largely intact, but gone is the novel’s step by step approach of taking half of each story, then moving forward; instead the six time periods each get a set-up, then run simultaneously, frequently cutting back and forth at significant points of intersection. There’s a nominal lead in each period: Jim Sturgess is Adam Ewing in 1849, an America lawyer conducting business in the Chatham Islands who gets caught up with a slave and falls under the care of a doctor (Tom Hanks); Ben Whishaw is Robert Frobisher in 1936, a frustrated composer (who’s also bisexual) and who takes a job as an amanuensis (and no, I’d never heard of that either) to Jim Broadbent’s Vyvyan Arys to allow time to finish his own work; Halle Berry is Luisa Ray, a journalist in 1973 who investigates a nuclear reactor run by Lloyd Hooks (Hugh Grant); Jim Broadbent is Timothy Cavendish, a publisher in 2012 who gets into trouble after one of his clients (Tom Hanks) commits a notorious act and turns to his brother (Hugh Grant) for help; Doona Bae is Somni-451, a clone worker at a restaurant in 2144 who goes on the run with a rebel freedom fighter (Jim Sturgess); and Tom Hanks is Zachry, a tribesman living in The Valley at an indeterminate point in the far future who attempts to help a futuristic visitor to his valley (Halle Berry) after his family and friends are attacked by another tribe (led by Hugh Grant).

With me so far? One of the bigger achievements of Cloud Atlas is the clarity and sense of narrative purpose. It’s always clear who’s doing what, what’s going on when, which time period we’re in and despite the frequent cutting, audiences should have little difficulty keeping track of the various plot strands. To call it a roller coaster ride would be to undersell roller coasters somewhat, as the six different stories have wildly differing tones from the outset: you get period drama, conspiracy thriller, broad farce and sci-fi action, often repeatedly in random orders, but somehow the six stories – the first and last two directed by the Wachowskis, the middle three by Tom Tykwer – work together and actually serve to complement each other. There’s connective tissue at work, some subtle and some more obvious, and plenty of themes at work, but it might take more than one viewing to attempt to unpack them all. What you can’t say about Cloud Atlas is that it’s ever dull, and while some might feel at two hours and fifty minutes it’s too long (a view I don’t subscribe to), it’s hard to see where too many cuts could have been made without excising an entire narrative.

But let’s not beat about the bush: it’s bonkers. Completely, utterly nutty as a fruitcake, and the decision to cast so many actors in so many roles is often more than a little distracting as it becomes one giant game of Guess Who? Five of the main actors (Hanks, Berry, Sturgess, Grant and Hugo Weaving, more often than not a villain of sorts in each thread) appear in every segment, two of them cross-dress and all of them cross-race at some point – and Hanks’ Oirish accent has to be heard to be disbelieved, and most of the final strand is spoken in a sort of pidgin English that sounded eerily reminiscent of the jive talking sections in Airplane! – and it’s occasionally easy to get lost attempting to work out who a certain person in a scene is, rather than focussing on the plot. Directorially, the work’s been divided reasonably between the collaborators; the Jim Sturgess on a boat scenes struggle the most to stay alive, possibly as the Wachowskis don’t have as much in the way of gimmicks, while their Korean strand is the most provocative, but the two past Tykwer segments are the most satisfying dramatically. If you don’t like one story, don’t worry, there’ll be another one along in a moment, and while I’d struggle to call Cloud Atlas a great film, it’s almost always a compelling one. Surely, though, it can only be a matter of time before someone attempts the great unfilmable book, the telephone directory? You wouldn’t put it past the Wachowskis on this evidence.

Why see it at the cinema: Revel in the madness. There’s a few intentional laughs which will benefit, and a few possibly unintentional which work just as well and a couple of the narrative strands, most notably the two futuristic ones, have a decent sense of scale and spectacle that work well.

What about the rating: Rated 15 for strong language, once very strong, strong violence and sex. Given that the details on the BBFC’s extended classification range from blood spurts to a graphic description of a sex scene, there would probably have had to have been a good 2 – 3 minutes of cuts to secure a 12A, and there can be no complaints at the 15 level.

My cinema experience: Pre-booked my ticket online to collect from the machine and headed straight in for a reasonably packed Saturday afternoon showing, but in the interests of full disclosure I made a massive cock-up which caused me to miss between five and ten minutes of the film about an hour in. When parking at the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds, I pay for the car parking by text message using my number plate, a wonderful modern convenience, and one which I never gave a thought to until an hour into the film, when I remembered I had driven my wife’s car that day (she’d taken mine to work) and so I’d paid to park the wrong car.

With no small change on me for the parking machine and a complex registration process to undergo to do the text parking thing for my wife’s car, I took the only reasonable option: I ran to the expensive cashpoint in the cinema foyer, got a ten pound note, paid for the cheapest thing I could see at the concessions (turned out to be an apple Capri-Sun, causing some bizarre flashbacks to childhood), ran to the car park with a Capri-Sun in my pocket, paid for the car parking just before the attendant got to my floor and would have spotted my faux pas and then ran back to the cinema to enjoy a very sweaty child’s drink and get my breath back. A surreal experience that felt somewhat in keeping with the film, and provided a useful intermission to break up the near three-hour running time.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Of course, what you want with a film with a running time north of 170 minutes is the briefest amount of trailers and adverts, which Cineworld failed to deliver. Twenty-eight minutes of ads of varying kinds before the film, one of the longest of my year so far, meaning anyone seeing that from the start would be sat for three hours and ten minutes; not good.

The Score: 8/10

Review: Side Effects

The Pitch: You may be about to suffer severe withdrawal symptoms…

The Pitch: You may be about to suffer severe withdrawal symptoms…

The Review: If you look in the dictionary for the definition of the word eclectic, you’ll see that it was updated a couple of years ago to read simply “Steven Soderbergh’s career.” Not content to be like namesake Spielberg and to successfully straddle the multiplex and more thoughtful fare, it’s as if Soderbergh deliberately sets out to distance himself from as many elements of his previous work as possible. Even his Ocean’s sequels varied wildly in tone, style and content, with Thirteen almost feeling the odd man out for being a little reminiscent of the original. When you use a phrase like “Soderbergh’s career” it has a certain finality to it and if the rumours are to be believed then Side Effects is the last time we’ll see a new film from Steven, at least for a fair while, so that Side Effects proves to be a surprisingly efficient and taut thriller and a fitting valediction for one of the last two decade’s most distinctive cinematic voices.

That his films are so recognisable may be down to the sheer level of work he puts into their production; over the years he’s written, produced and even composed and Side Effects sees him working as editor, cinematographer and director on the same film for the sixth time in his career. It’s a refined, almost cold visual aesthetic but one that is subject to deliberate rhythms and pacing, and this might just the the most effective combination of those three skills yet. It’s a slow start as regular Soderbergh scribe Scott Z. Burns sets out the playing field, with Rooney Mara’s Emily struggling to deal with the return of husband Martin (Channing Tatum) from prison after a stretch for insider dealing. When she attempts to deal with her onset of depression in dramatic fashion, she comes under the care of psychiatrist Jonathan Banks (Jude Law) who attempts to find the right drug to help her deal with her difficulties. It’s not the first time that Emily’s needed help, and her previous counsellor Victoria (Catherine Zeta-Jones) suggests a new drug, Ablixa, might be the best option of those not already tried, but it may just be the start of Emily’s real problems…

Soderbergh’s back catalogue is written through Side Effects like a stick of rock: as well as the crisp digital photography and the economy of the script, which never wastes a word even during the deliberately paced set-up. He’s got form in the political arena, and for the opening stretch Side Effects seems to be setting itself up as a thorough examination of the cynical and profitable pharmaceutical industry that’s practically spoon fed to most of America. (There’s an interesting, and telling, line where Jude Law comments on the difference between his practice in the US and how different it would have been in the UK had he stayed.) But it’s also never that simple in a Soderbergh film and there’s enough twists and turns packed into the second half to keep even the sharpest audience on their toes. The more the film progresses, the more the narrative takes on a classic feel, and it wouldn’t have been a stretch to imagine Bernard Herrmann coming up with a similarly jittery score to Thomas Newman’s nervous stylings, or indeed the likes of Cary Grant or James Stewart taking on the Jude Law role had this been made fifty years ago.

Soderbergh’s always been an actor’s director at heart, ultimately as concerned with performance as he is with image, and most of the cast have become regular collaborators. While Zeta-Jones and Tatum are both on their third outing with the director, it’s Jude Law’s sophomore turn that anchors Side Effects, and it’s around 1000% more effective than his embarrassing Australian from Contagion. Where Contagion was chilling but sprawling and at times unfocused, Side Effects coils itself more and more tightly and it’s a showcase both Law and first-timer Rooney Mara, utterly believable as the depressive Emily. It’s undoubtedly a film of its time, with much to say about modern lives and current struggles, but it’s possibly writer Burns’ most effective script to date and it’s hard to imagine anyone except Steven Soderbergh working today being able to play it out so effectively, especially in the way that possibly sensitive themes such as depression and the financial crisis are not only handled, but then not undermined when the narrative takes one sharp turn after another. It’s maybe fitting that someone so focused on the image of his films is supposedly taking his break to work on his painting, but given that he’s still got cinematic treats like this within him, let’s all hope that it’s just a sabbatical and not the last we’ll see of him.

Why see it at the cinema: Soderbergh is a master of his art and every image and sound is lovingly crafted. The darkness of the cinema will also help focus you into the tightly wound tension that Soderbergh crafts, especially in the second half.

What about the rating: Rated 15 for strong language, sex and violence. No argument, and it’s certainly a more effective film at this rating as it’s really one pivotal scene that earns this rating, which would have lessened the overall impact had it been cut to 12A.

My cinema experience: Saturday morning at my local Cineworld in Cambridge; having pre-booked my ticket I thankfully sailed through to the cinema, to be joined by the usual crowd of single men taking in a Saturday morning film with clearly nothing better to do. Thankfully we weren’t submitted to any projection problems.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: The film started twenty-three minutes after the advertised time, which for me was a complete relief; having struggled to find a parking space I arrived in just as the BBFC title card appeared on screen.

The Score: 9/10

Review: Oz The Great And Powerful

The Pitch: We’re off to make the wizard, the wonderful wizard of Oz.

The Review: Origin stories are a curious phenomenon. It seems you can’t start a comic book franchise without first explaining how characters have obtained their superpowers, as if some justification is required for otherworldly abilities rather than just plain, old fashioned story-telling. The question will always be if these stories are worth telling: no one has yet decided to put pen to paper to attempt to explain whether the Three Little Pigs had endowment or repayment mortgages, or wondered whether The Three Bears sourced the home furnishings that so aggrieved Goldilocks from IKEA or some other home furnishing store. But Sam Raimi has seen a gap in the market: how did the man behind the curtain get behind the curtain in the first place? Is the wizard’s story as compelling as that of Dorothy, or indeed any of the other characters outlined in L. Frank Baum’s fourteen novels based in and around the land of Oz?

As with any venture which calls on well-known or beloved characters, there’s a risk of going too far to either extreme; if you don’t use the existing characters enough, then you’ll alienate the core audience, but fail to include freshness or originality and your purpose will seem false. The restriction that Raimi and Disney had to work under is that Baum’s original novel is now in the public domain, but the original Warner Brothers adaptation from 1939 isn’t, so elements introduced by that adaptation were strictly off limits. This still leaves a pretty open playing field, as long as you don’t want to be wearing ruby slippers (originally silver in the novel), but since this is the wizard’s story, not Dorothy’s, there’s less conflict than you might think. Some excised or ignored elements from the source do make an appearance here, including a land made of china cheekily renamed Chinatown – but this prequel errs on the side of the familiar rather than the fresh.

Indeed, some of the performances feel as if they’ve been lifted directly from 1939, not least James Franco’s cheesy, surprisingly lively interpretation of the titular Oz. Franco’s often gravitated to withdrawn, offbeat roles and it’s certainly the latter, if absolutely not the former in this case. His performance might be an acquired taste, but it’s just one of a number of broad turns which include the witches three (Michelle Williams, Rachel Weisz and Mila Kunis) and some motion-capture LOLs from the wizard’s sidekicks (Zach Braff and Joey King) that stop just short of pantomime. The overall feel is very much in the same vein as Tim Burton’s recent Alice In Wonderland, from the neon brightness of much of the CG backgrounds to the typical Danny Elfman score, but with Raimi, as he so often did with the Spider-Man films, just occasionally adding his own specific flourishes.

What unfolds over the slightly bloated two hour plus running time can be broadly broken down into three phases; the opening twenty minutes, shot as the original Oz was in black and white before unleashing the colour, and featuring some faces of the key players in both narratives; then the tornado lifts Oz and his balloon and it’s practically a theme park ride until Oz encounters other characters in what at first appears to be a sparsely populated land; and finally we settle into the actual story, where Oz looks to understand who he really is. If that sounds like the sort of hackneyed moral that normally underpins middle of the road animation, then it absolutely is, but the gentle humour and the simple characters actually serve to elevate it. It’s hardly revolutionary, but there’s a certain amount of charm in watching how the various elements of the original story fall into place, and while it can’t compare to the 1939 Wizard adventure (or indeed, even the dark charms and originality of the almost cult classic Eighties sequel Return To Oz, which did a better job of drawing on the source material), it’s an entertaining ride that just about justifies its existence.

Why see it at the cinema: Raimi goes big on the visuals and throws in a few trademarks, including POV shots, and there’s no shortage of spectacle or detail, all of which make this a worthwhile experience to make the trip out for.

Why see it in 3D: You’ll notice that the title of this review doesn’t have a “3D” suffix as I saw it in 2D, but I’m going to strongly recommend that you see it in 3D if you can based on what I saw. Not only does Raimi have a good go at two different styles of 3D, including the waving-stuff-in-your-face and also the layered perspective mastered so well by Ang Lee in last year’s Life Of Pi, but seemingly to compensate for the brightness issues of 3D the day-glo aspects have been ramped up, and there were a couple of scenes which cut from darkness to bright sunshine quickly which caused my corneas to attempt to retreat into the back of my head. Even now, the next day, I think there may be images of flying baboons seared onto my retinas, so if you can see this wearing sunglasses – frankly in 2D or 3D – I’d suggest it’s the better option.

What about the rating? Rated PG for mild fantasy threat. The key line is in the BBFC’s extended classification info, where it states that “a PG film should not disturb a child aged around eight or older.” I would just advise a little caution if taking children younger than that, as it’s an occasionally dark film that might trouble the very young.

My cinema experience: Saw this at the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds, where I was instantly plied with chocolate – a combination of a two for £4 offer on bags of chocolate and our Unlimited Premium discounts meant I got a large bag of Maltesers for effectively 75p – and a sparse and talkative audience thankfully seemed unfazed by the first twenty minutes being in black and white, Academy ratio. (I know at least one other Cineworld has been tweeting this out regularly to try to avoid complaints.)

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Tidy. Just three trailers and a meagre selection of public service announcements meant that it was a mere 21 minutes between advertised start time and actual film start time.

The Score: 7/10

The Half Dozen: 6 Most Interesting Looking Trailers For March 2013

Ever the seasons shift, and spring is almost upon us. But the movie seasons shift even further; already, summer blockbusters have advanced to the middle of April, Tom Cruise’s expensive looking Oblivion (which sounds like a metaphor for his career now I read it back) arriving two weeks before Robert Downey Jr. gets out the red and gold suit again and gets fanboys around the world just a little excited. But come next year, awards season may not have concluded by the end of February, with every weekend taken up with Superbowls and Winter Olympics that there’s talk of the Oscars shifting later into March, the normal lull that occurs around this time of year may by 2014 be swallowed up completely between frippery and giant explosions.

So what will happen to March next year? Sure, it’ll still be on the calendar, and short of some sudden recalculation by boffins it’ll still be made up of 31 days, but the films that find respite from the need to garner awards or giant box office will have nowhere else left to go. You might be wondering what kind of film that is, but given that less than two dozen films normally sweep the fields at awards time – even in a well spread year like 2013’s various shindigs – and once the blockbusters start you’ll barely be able to find more than two or three different films showing at your local sixteen screen multiplex, so these periods of breathing space are vital for something more nourishing but less bombastic to find screening time.

As to what kind of films find their screen time in this season, it seems to be the case this year that it’s the kind of film that normally finds a home at the opposite end of the year in the normal follow-on from blockbuster season: festival season. This first became apparent when I was performing my normal trawl through the listings at the likes of Rotten Tomatoes, IMDb and Launching Films to see what’s due out this month, and I realised I’d seen a decent number of films already that were due out in March. Long time readers will know that there is only one rule of The Half Dozen – that I never include trailers for films I’ve already seen – so it seemed a sensible time to read this rule the last rites.

Yes, here are six trailers for films, all of which I’ve already seen. (I’m such a rebel.)

Stoker

Okay, you got me, to start proceedings off I was one short, so this the first film I’ve seen this month. Leaping straight into my top five of the year is the first English language film from Park Chan-wook, one of Korea’s foremost directors and best known internationally for his Oldboy and various films with the word Vengeance in the title. Not much vengeance on the go here, but there is some subtle horror, mood aplenty and more literary allusions than you can shake a stick at, and it all hangs together beautifully.

Sleep Tight

I will confess, despite this appearing on all of the aforementioned lists I can’t actually find a single cinema playing this, so I hope you have more luck as this is well worth seeking out; I caught it in the Late Night Frights at last year’s Cambridge Film Festival. Spanish actor Luis Tosar is one of those familar faces that you just can’t quite place, so he’s perfect casting for this creepy thriller from director Jaume Balaguero ([REC], [REC] 2, disappointingly not yet [STOP] or [FF]) where Tosar’s concierge tries to understand the secrets of his apartment building tenants, while keeping a fair few of his own.

Robot & Frank

Now this film will have a particular place in my heart for years to come, for it’s the first film I ever saw at the London Film Festival and consequently the first time I ever got to walk along an actual red carpet, along with the rest of the audience. I always get a buzz from being in Leicester Square, cinematic Mecca for mainstream obsessives like myself and nexus of the LFF, and at the Odeon West End I was utterly besotted with this unlikely relationship tale of a man and a giant walking, talking iPhone and their even more unlikely adventures. I decided to shift it to this year’s run-down, where if it doesn’t make my top 10 of the year by year end it will have been an extremely good year for film.

Maniac

Saw this one at the end of a very long day at FrightFest 2012 at the Empire Leicester Square last August. What turned out to be a very mixed day – and probably the weakest of the festival in hindsight – started with me heading into London for 10 a.m. to catch a documentary on Eurocrime and finished six films and eleven hours later with this remake of a dirty Eighties movie, re-imagined as a first person slasher with Elijah Wood in the title role. Wood is creepily effective, the perspective is used ingeniously and it’s not afraid to go to some very dark places. As did I when I rolled out at 1:30 a.m. for the nightbus, getting back to my car at 3 a.m.

John Dies At The End

Another London Film Festival showing, this one at the almost brand spanking new Hackney Picturehouse. My previous memory of director Don Coscarelli’s work was watching Bubba Ho-Tep on a tiny monitor on the first class video screen (thanks to the upgrade Mrs Evangelist had blagged us) on the way back from my honeymoon, and I wasn’t overly impressed then; thankfully John Dies At The End is more of a rip-roaring, off the wall journey into insanity adapted from Jason Pargin’s novel, and while it’s not lived hugely long in my memory it was most entertaining in the moment. And does John die at the end? That would be telling.

Finding Nemo 3D

Finally one that we’ve probably all seen, and if you haven’t then stop right now, head to LoveFlix or NetFilm or one of those new-fangled jobbies and soak in one of the films I fear will come to be known as Pixar’s Golden Period, before the likes of Cars 2 and Brave descended and it wasn’t the case that every single film that Pixar produced is outstanding.

Hang on a minute – did I just tell y0u to go and rent a film that’s coming back to cinemas?! I must be losing my mind. What a clownfish.

Review: A Good Day To Die Hard

The Pitch: Hope That I Die Hard Before I Get Old. (Ah, too late.)

The Pitch: Hope That I Die Hard Before I Get Old. (Ah, too late.)

The Review: Alchemists have tried and failed for all of human history to find a way of converting base metals into gold. For all of our understanding of elements and their combinations driven by thousands of years of science, that understanding has not driven a way to be able to produce quality from just anything, and the same can be said for films. Somehow the Die Hard franchise produced what’s seen by many as the gold standard of action movies, a standard that has endured to this day and a series which has produced varying quality but never truly disappointed. Until now. I’m not going to beat about the bush, A Good Day To Die Hard is dreadful on almost every conceivable level; the only mystery is how a formula which seemed to be the alchemist’s dream, almost impossible to get wrong, has been so badly handled by Skip Woods, John Moore and Bruce Willis.

Let’s take each of the main culprits in turn. First of all, a hallmark of the Die Hard series has been their ability to handle an action scene, with previous directors John McTiernan, Renny Harlin and even Len Wiseman all knowing where to put the camera, how to frame the shots for maximum impact and how to generate pace and tension. John Moore has none of these skills and the action scenes are bland and repetitious. The crucial failing seems to be confusing John McClane with The Terminator, for while the previous four films all understood how to show a man bravely / stupidly venturing into unlikely situations, and occasionally barrelling head first into stupidity, here McClane rampages around in a manner that would make a T-1000 malfunction. Consequently any possible sense of drama or tension has evaporated before we even reach the halfway mark, and the majority of the running time is a procession of dull, repetitive stunt work – McClane gets attacked by a helicopter shooting at a building not once, but twice.

Writer Skip Woods hasn’t exactly given him a lot to work with. This fifth dying of the hard variety is unique in the sense it was written as a Die Hard film, rather than being retooled from an existing script, and on this evidence that was a worse idea than diving off a building tied to a fire hose or driving a car into a helicopter. I could reel off all of the elements that should have made the script and didn’t – and we’re talking fundamentals like a plot, decent bad guys and some form of development for the man always in the wrong place at the wrong time – but it’s just a shame someone didn’t do that for Woods before he fired up his laptop. The Die Hards have always managed to work up a reasonable amount of intrigue and get McClane to do some actual police work, but here he stumbles around blindly in search of narrative and here has less luck finding story here than he normally has finding trouble.

The Die Hards have always had a fantastic array of supporting characters, blessed with both quality and depth and helping to underpin the world-weariness and warmth in McClane’s character. Take away that quality and depth and Bruce Willis just appears bored and shouty, and if the bad guys had a nanogram of charisma between them you’d be rooting for them instead. Everyone seems to think that you throw another McClane into the mix and that’s enough, but Jai Courtney and Bruce Willis have zero family chemistry, and by the time of the ill-advised excursion to Chernobyl – where science and logic bid a sad farewell to all participants – the end can’t come quickly enough. Whatever the recipe was here, the previously golden Die Hard series has been turned to something browner and much more leaden. Something in me feels that, if I’d put my mind to it, I could have been much more insulting about AGDTDH, but if no-one involved with the film can be bothered, why should I?

Why see it at the cinema: You’d be better off blindfolding yourself, then beating yourself over the head with a piece of wood with a blunt nail in it. Not only will it be less painful, but the fact that sometimes you’ll hit yourself with the nail and sometimes you won’t adds a variety and sense of danger that A Good Day To Die Hard is sorely lacking.

What about the rating? Rated 12A for strong language and moderate action violence. The big controversy here, if you didn’t somehow hear about it being ranted extensively on Twitter and blogs the length and breadth of the country, is that the US got an R-rated version (broadly equivalent to our 15) and we got the neutered, less mother abusing 12A version. Anyone that thinks this was (a) anything other than a desperate ploy to feel a steaming pile of detritus to the masses, and (b) denying us a much higher quality 15-rated film based on extra swearing and blood sprays, is as wrong as everyone involved in the making of this sorry pile.

My cinema experience: I sat in a cinema hating myself and everyone involved in this for an hour and a half. (It was the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds.) I’d only gone to see it in an effort to truly compare the efforts of the new Arnie, Sly and Bruce movies; Arnie wins this one hands down. Two people claimed to have enjoyed themselves as I heard them talking on the way out; they desperately need higher standards, and it made me pine for the feeling I had about Die Hard 4.0 at the same cinema. At least the cinema suffered no sound or projection issues, but for a first weekend Saturday evening showing it was a desperately thin and uninvolved audience.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Thankfully the experience was only prefaced by twenty minutes of ads, trailers and the other usual guff, meaning the agony wasn’t prolonged for too long.

The Score: 2/10

Review: Hitchcock

The Pitch: Sasha Gervasi Presents. (Doesn’t have the same ring, does it?)

The Pitch: Sasha Gervasi Presents. (Doesn’t have the same ring, does it?)

The Review: Good evening. I have for you tonight a devious little entertainment, which will shock and surprise you in ways you weren’t expecting. It’s the story of a man who took delight in the more unpleasant side of life and the relationship between men and women, and how the story of a serial killer tortured him to the point of madness. It’s a tale of love, hate, commitment and betrayal, but you’ll be truly terrified by the leading man and what he’s capable of; or should I say, what he’s not capable of? You might think you’ve heard this story before, even very recently, and you probably have, but what’s more likely to keep you guessing than a story that plays out exactly as you think it will? If you know your history, especially your history of Psychos, then you may think that you know the ending, where a film becomes highly successful but also highly notorious, and with a legacy of not only most mainstream horror movies produced since, but also smaller moments which would prove pivotal. But of course, you don’t know this story at all.

Right, enough of the double talk, Hitchcock himself wouldn’t have been a fan of such obfuscation. This is a man that made a trailer for Psycho by walking round the set and all but giving away the main plot points in every location, never spoiling but teasing to the point of genius. This is a man who was extremely aware of not only his own self-image but the need for good marketing to support a good product, a combination never more completely brought together than in the marketing and production of Psycho, certainly not his best film but perhaps his most notorious (and from a man that made Notorious, that’s no mean feat). This is a man who looks nothing like Anthony Hopkins in a fat suit doing an intermittent accent, but at least they got the infamous silhouette correct; George Clooney looks about as much like the real Alma Reville as Helen Mirren does. But it’s a man who would, I’m sure, not have approved of the straightforward nature and simple moralising of his own biopic; we should maybe just be thankful that it’s not the same hatchet job that the BBC’s TV movie The Girl turned out to be just a couple of months earlier.

So what works? Taken as a drama on its own terms, and putting aside any association with its subject matter, Hitchcock is passably interesting as an effective period piece or a TV movie of the week. It might be cookie-cutter drama with simple characters, but it has a timeless quality and uses simple themes well. Some of the minor casting is also eerily effective, with James D’Arcy an uncanny double of Anthony Perkins and Scarlett Johansson actually not a million miles away from Janet Leigh, at least in comparison to the leads. The likes of Danny Huston also turn up and do what they do best in less familiar roles. And again, if you disassociate yourself from the source material, the performances of Hopkins and Mirren aren’t bad, they’re just not particularly representative of their real life counterparts in either appearance, mannerism or character from all of the available evidence.

That’s balanced out by the list of what doesn’t work, and it’s not a short list. On top of the failure of Hopkins and Mirren to inhabit their real life counterparts, its attempts to act as a primer on the making of Psycho are muddied at best, and some moments – such as when Hitch and “Bernie” Herrmann are discussing the merits of scoring the key shower scene or leaving it silent – simply don’t work in the context of the drama. Worse still, there’s a consistent device where Hitch interacts with Ed Gein, real life killer on whose exploits Psych was based, which not only undercuts matters further but implies consequences of screen violence that patently aren’t true, selling Hitchcock’s real life’s intentions painfully short. Many of the supporting characters are cyphers and plot devices, and when it’s all over it’s not particularly clear what it was trying to achieve, a feat clearly at odds with how Hitch constructed his own pointed narratives. Even the opening and closing appearances of Hitch talking to camera, in the manner of the “Alfred Hitchcock Presents…” TV Series with their famous Gounoud theme music playing into Danny Elfman’s anonymous score, are more jovial than the dry intros of the master himself in that series. It would seem the best way to learn about Psycho, and the power of cinema itself, is just to rewatch Psycho. It will certainly be, if you’re much like me, a lot more enjoyable. Until the next time, good night.

Why see it at the cinema: The real Hitch would no doubt approve of you being summoned to the cinema, it’s just a shame that what’s been served up is so utterly lacking in its own cinematic aspirations.

What about the rating? Rated 12A for moderate horror, threat and sex references. Most of the material that made Psycho a 15 rating is merely hinted at here, but it’s not one I’d be taking younger children to.

My cinema experience: A weekday afternoon at the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds, and a largely uneventful screening passed off among a small audience. Not for the first time at Bury, the curtains which wound back before the start of the main feature sounded like they could do with a good oiling. Remind me and next time I’ll bring the WD40.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Hideous. Five full length trailers, adverts and a host of PSAs (including the one from Hitchcock itself with good ol’ Hitch advising you to turn off your mobiles) meaning that the BBFC title card came up for the start of the film thirty-one minutes after the advertised start time.

The Score: 5/10