review

Review: Trance

The Pitch: Games of the mind.

The Review: Danny Boyle, hero of the Olympic Games and now almost a socialist icon for apparently turning down a knighthood. You could be forgiven for forgetting he also makes films, being responsible for some of the most iconic British films of the last two decades. He’s certainly a contemporary film maker, and from his pioneering work with cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle in pushing digital films to the soundtracks laced with the likes of Underworld, Boyle’s never been afraid to push boundaries or to keep pace with the times. He could almost be accused of retreating into his comfort zone with Trance, for not only are Mantle and Underworld’s Rick Smith on board once more, but screenwriter John Hodge – responsible for Boyle’s first two films, and two of his greatest triumphs, in Shallow Grave and Trainspotting – is also back on scripting duties. But Boyle’s often been left at the mercy of his screenwriters, heavily dependent on the quality of the writing, so it’s understandable he’d want to try to replicate the success of those early collaborations.

There are clear parallels with Shallow Grave in the central trio of characters, Hodge once again exploring themes of power and control between three central characters, two male and one female. In Trance’s case, we’re first introduced to Simon (James McAvoy), who’s caught up in a robbery at the auction house where he works. When he confronts the gang leader Franck (Vincent Cassel), Franck lashes out and a blow to the head causes Simon to forget details of the robbery, crucially including where the painting’s disappeared to when Franck ends up with just the empty frame post-robbery. Running out of ideas when attempts to intimidate and torture the info out of him fail, Franck sends Simon to hypnotherapist Elizabeth (Rosario Dawson) in the hope of unlocking the secrets in Simon’s fractured mind, but Elizabeth begins to find more than any of them bargained for.

Shallow Grave was concerned with the moral implications of simple greed, and that sense of greed is also heavily prevalent in Trance. Hodge’s script (based on an original TV movie by Joe Ahearne, who also collaborated with Hodge here) is more keen than Shallow Grave was to misdirect and obfuscate, and the clean lines of Boyle and Hodge’s first team-up are replaced with something altogether more brittle and hazy. The clearest parallels are not in the roles of the three central characters – although McAvoy’s cocksure young auctioneer reminiscent of Ewan McGregor’s journalist Alex in Grave and Rosario Dawson exhibits a similar strength to Kerry Fox’s doctor Juliet – or even in the sense of identity born out of the city location (London here, Edinburgh there) but in the sense of shifting loyalties and absence of trust. The big difference lies with the former film’s ability to empathise with any of the three characters at various points, no matter whether they were charming, obnoxious or just plain deceitful, but sadly Simon, Franck and Elizabeth are all cold, heartless ciphers who make it impossible to connect with any of them.

While the characterisation is a let-down, the plot does take a number of satisfying twists and turns, but for once Boyle compounds the errors of his screenwriter rather than compensating for them by falling into a number of genre conventions of both psychological and body horror. It’s as if Boyle can’t help but put up giant neon signs, fond of both the literal neon gaudiness of his post-Olympian London and allowing that to seep into his plotting with metaphorical signposts indicating “Rug about to be pulled here” and “This isn’t what you think it is.” Sadly it leaves Trance crucially lacking in surprises most of the time and the details of the denouement are more easily pieced together. Some might find the occasional horror imagery difficult to stomach; having no such difficulties myself I was more troubled by such difficulties as the amount of screen time the no-dimensional hoods backing up Franck are given. The plot might be the only thing that makes Trance worth seeing, but once you’ve worked out where its headed you won’t need a hypnotherapist, as Trance is eminently forgettable all on its own. Better luck next time, Sir Danny.

Why see it at the cinema: Anthony Dod Mantle’s crisp cinematography remains at the forefront of the digital artform and Boyle can still compose an image, even if he has gone slightly over the top with the Dutch angles.

What about the rating: Rated 15 for strong bloody violence, gore, sex, nudity and strong language. Or, as the teenage boy inside me would call it, the Grand Slam. While everything here is typical Boyle, it’s never quite pushed as far as his early career and 15 feels right, if just a shade disappointing and commercial.

My cinema experience: Just over half full at the Cineworld in Cambridge for an Unlimited preview showing, with a nice if somewhat half-hearted intro from Danny Boyle himself. Still, it’s nice he made the effort. Tucked away in one of the smaller screens, but one apparently with decent sound and projection.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Thanks to it being an Unlimited preview showing, just trailers and the latest Kevin Bacon EE advert, it was just a minimalist thirteen minutes before the Danny Boyle intro. If only all films were like that…

The Score: 6/10

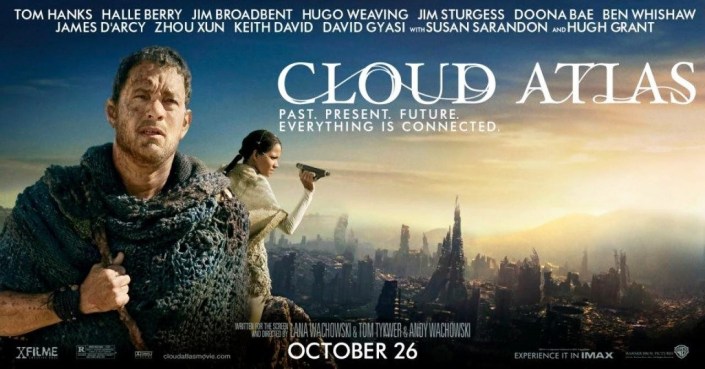

Review: Cloud Atlas

The Pitch: All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players: they have their exits and their entrances, and one man in his time plays many parts…

The Review: Calling all authors! Cinema is taking on any challenge you can throw at it, and over the past few years one book after another previously claimed to be beyond even the most artistic and ambitious directors, from the Lord Of The Rings to Life Of Pi. Since they’ve not only been adapted, but often to universal critical acclaim, the search must be on for a novel which is genuinely unfilmable. If you’d like a challenge, surely you’d take on a book that’s actually six different stories, nested one inside the other, each told with a different writing style and working in a different genre, with masses of linking themes and recurring motifs. If you really want to make sure you’re testing yourself, you’d divide the load between two contrasting sets of film makers, one known for period and contemporary works and one pair who have a reputation for unbalanced and challenged futuristic works, but you wouldn’t necessarily divide the work between them along those lines. Then for good measure you’d mix all six narrative threads together, and cast thirteen different actors to play sixty-four different parts across the six narratives… Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Cloud Atlas.

So the six narratives from David Mitchell’s original novel remain largely intact, but gone is the novel’s step by step approach of taking half of each story, then moving forward; instead the six time periods each get a set-up, then run simultaneously, frequently cutting back and forth at significant points of intersection. There’s a nominal lead in each period: Jim Sturgess is Adam Ewing in 1849, an America lawyer conducting business in the Chatham Islands who gets caught up with a slave and falls under the care of a doctor (Tom Hanks); Ben Whishaw is Robert Frobisher in 1936, a frustrated composer (who’s also bisexual) and who takes a job as an amanuensis (and no, I’d never heard of that either) to Jim Broadbent’s Vyvyan Arys to allow time to finish his own work; Halle Berry is Luisa Ray, a journalist in 1973 who investigates a nuclear reactor run by Lloyd Hooks (Hugh Grant); Jim Broadbent is Timothy Cavendish, a publisher in 2012 who gets into trouble after one of his clients (Tom Hanks) commits a notorious act and turns to his brother (Hugh Grant) for help; Doona Bae is Somni-451, a clone worker at a restaurant in 2144 who goes on the run with a rebel freedom fighter (Jim Sturgess); and Tom Hanks is Zachry, a tribesman living in The Valley at an indeterminate point in the far future who attempts to help a futuristic visitor to his valley (Halle Berry) after his family and friends are attacked by another tribe (led by Hugh Grant).

With me so far? One of the bigger achievements of Cloud Atlas is the clarity and sense of narrative purpose. It’s always clear who’s doing what, what’s going on when, which time period we’re in and despite the frequent cutting, audiences should have little difficulty keeping track of the various plot strands. To call it a roller coaster ride would be to undersell roller coasters somewhat, as the six different stories have wildly differing tones from the outset: you get period drama, conspiracy thriller, broad farce and sci-fi action, often repeatedly in random orders, but somehow the six stories – the first and last two directed by the Wachowskis, the middle three by Tom Tykwer – work together and actually serve to complement each other. There’s connective tissue at work, some subtle and some more obvious, and plenty of themes at work, but it might take more than one viewing to attempt to unpack them all. What you can’t say about Cloud Atlas is that it’s ever dull, and while some might feel at two hours and fifty minutes it’s too long (a view I don’t subscribe to), it’s hard to see where too many cuts could have been made without excising an entire narrative.

But let’s not beat about the bush: it’s bonkers. Completely, utterly nutty as a fruitcake, and the decision to cast so many actors in so many roles is often more than a little distracting as it becomes one giant game of Guess Who? Five of the main actors (Hanks, Berry, Sturgess, Grant and Hugo Weaving, more often than not a villain of sorts in each thread) appear in every segment, two of them cross-dress and all of them cross-race at some point – and Hanks’ Oirish accent has to be heard to be disbelieved, and most of the final strand is spoken in a sort of pidgin English that sounded eerily reminiscent of the jive talking sections in Airplane! – and it’s occasionally easy to get lost attempting to work out who a certain person in a scene is, rather than focussing on the plot. Directorially, the work’s been divided reasonably between the collaborators; the Jim Sturgess on a boat scenes struggle the most to stay alive, possibly as the Wachowskis don’t have as much in the way of gimmicks, while their Korean strand is the most provocative, but the two past Tykwer segments are the most satisfying dramatically. If you don’t like one story, don’t worry, there’ll be another one along in a moment, and while I’d struggle to call Cloud Atlas a great film, it’s almost always a compelling one. Surely, though, it can only be a matter of time before someone attempts the great unfilmable book, the telephone directory? You wouldn’t put it past the Wachowskis on this evidence.

Why see it at the cinema: Revel in the madness. There’s a few intentional laughs which will benefit, and a few possibly unintentional which work just as well and a couple of the narrative strands, most notably the two futuristic ones, have a decent sense of scale and spectacle that work well.

What about the rating: Rated 15 for strong language, once very strong, strong violence and sex. Given that the details on the BBFC’s extended classification range from blood spurts to a graphic description of a sex scene, there would probably have had to have been a good 2 – 3 minutes of cuts to secure a 12A, and there can be no complaints at the 15 level.

My cinema experience: Pre-booked my ticket online to collect from the machine and headed straight in for a reasonably packed Saturday afternoon showing, but in the interests of full disclosure I made a massive cock-up which caused me to miss between five and ten minutes of the film about an hour in. When parking at the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds, I pay for the car parking by text message using my number plate, a wonderful modern convenience, and one which I never gave a thought to until an hour into the film, when I remembered I had driven my wife’s car that day (she’d taken mine to work) and so I’d paid to park the wrong car.

With no small change on me for the parking machine and a complex registration process to undergo to do the text parking thing for my wife’s car, I took the only reasonable option: I ran to the expensive cashpoint in the cinema foyer, got a ten pound note, paid for the cheapest thing I could see at the concessions (turned out to be an apple Capri-Sun, causing some bizarre flashbacks to childhood), ran to the car park with a Capri-Sun in my pocket, paid for the car parking just before the attendant got to my floor and would have spotted my faux pas and then ran back to the cinema to enjoy a very sweaty child’s drink and get my breath back. A surreal experience that felt somewhat in keeping with the film, and provided a useful intermission to break up the near three-hour running time.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Of course, what you want with a film with a running time north of 170 minutes is the briefest amount of trailers and adverts, which Cineworld failed to deliver. Twenty-eight minutes of ads of varying kinds before the film, one of the longest of my year so far, meaning anyone seeing that from the start would be sat for three hours and ten minutes; not good.

The Score: 8/10

Review: Side Effects

The Pitch: You may be about to suffer severe withdrawal symptoms…

The Pitch: You may be about to suffer severe withdrawal symptoms…

The Review: If you look in the dictionary for the definition of the word eclectic, you’ll see that it was updated a couple of years ago to read simply “Steven Soderbergh’s career.” Not content to be like namesake Spielberg and to successfully straddle the multiplex and more thoughtful fare, it’s as if Soderbergh deliberately sets out to distance himself from as many elements of his previous work as possible. Even his Ocean’s sequels varied wildly in tone, style and content, with Thirteen almost feeling the odd man out for being a little reminiscent of the original. When you use a phrase like “Soderbergh’s career” it has a certain finality to it and if the rumours are to be believed then Side Effects is the last time we’ll see a new film from Steven, at least for a fair while, so that Side Effects proves to be a surprisingly efficient and taut thriller and a fitting valediction for one of the last two decade’s most distinctive cinematic voices.

That his films are so recognisable may be down to the sheer level of work he puts into their production; over the years he’s written, produced and even composed and Side Effects sees him working as editor, cinematographer and director on the same film for the sixth time in his career. It’s a refined, almost cold visual aesthetic but one that is subject to deliberate rhythms and pacing, and this might just the the most effective combination of those three skills yet. It’s a slow start as regular Soderbergh scribe Scott Z. Burns sets out the playing field, with Rooney Mara’s Emily struggling to deal with the return of husband Martin (Channing Tatum) from prison after a stretch for insider dealing. When she attempts to deal with her onset of depression in dramatic fashion, she comes under the care of psychiatrist Jonathan Banks (Jude Law) who attempts to find the right drug to help her deal with her difficulties. It’s not the first time that Emily’s needed help, and her previous counsellor Victoria (Catherine Zeta-Jones) suggests a new drug, Ablixa, might be the best option of those not already tried, but it may just be the start of Emily’s real problems…

Soderbergh’s back catalogue is written through Side Effects like a stick of rock: as well as the crisp digital photography and the economy of the script, which never wastes a word even during the deliberately paced set-up. He’s got form in the political arena, and for the opening stretch Side Effects seems to be setting itself up as a thorough examination of the cynical and profitable pharmaceutical industry that’s practically spoon fed to most of America. (There’s an interesting, and telling, line where Jude Law comments on the difference between his practice in the US and how different it would have been in the UK had he stayed.) But it’s also never that simple in a Soderbergh film and there’s enough twists and turns packed into the second half to keep even the sharpest audience on their toes. The more the film progresses, the more the narrative takes on a classic feel, and it wouldn’t have been a stretch to imagine Bernard Herrmann coming up with a similarly jittery score to Thomas Newman’s nervous stylings, or indeed the likes of Cary Grant or James Stewart taking on the Jude Law role had this been made fifty years ago.

Soderbergh’s always been an actor’s director at heart, ultimately as concerned with performance as he is with image, and most of the cast have become regular collaborators. While Zeta-Jones and Tatum are both on their third outing with the director, it’s Jude Law’s sophomore turn that anchors Side Effects, and it’s around 1000% more effective than his embarrassing Australian from Contagion. Where Contagion was chilling but sprawling and at times unfocused, Side Effects coils itself more and more tightly and it’s a showcase both Law and first-timer Rooney Mara, utterly believable as the depressive Emily. It’s undoubtedly a film of its time, with much to say about modern lives and current struggles, but it’s possibly writer Burns’ most effective script to date and it’s hard to imagine anyone except Steven Soderbergh working today being able to play it out so effectively, especially in the way that possibly sensitive themes such as depression and the financial crisis are not only handled, but then not undermined when the narrative takes one sharp turn after another. It’s maybe fitting that someone so focused on the image of his films is supposedly taking his break to work on his painting, but given that he’s still got cinematic treats like this within him, let’s all hope that it’s just a sabbatical and not the last we’ll see of him.

Why see it at the cinema: Soderbergh is a master of his art and every image and sound is lovingly crafted. The darkness of the cinema will also help focus you into the tightly wound tension that Soderbergh crafts, especially in the second half.

What about the rating: Rated 15 for strong language, sex and violence. No argument, and it’s certainly a more effective film at this rating as it’s really one pivotal scene that earns this rating, which would have lessened the overall impact had it been cut to 12A.

My cinema experience: Saturday morning at my local Cineworld in Cambridge; having pre-booked my ticket I thankfully sailed through to the cinema, to be joined by the usual crowd of single men taking in a Saturday morning film with clearly nothing better to do. Thankfully we weren’t submitted to any projection problems.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: The film started twenty-three minutes after the advertised time, which for me was a complete relief; having struggled to find a parking space I arrived in just as the BBFC title card appeared on screen.

The Score: 9/10

Review: Oz The Great And Powerful

The Pitch: We’re off to make the wizard, the wonderful wizard of Oz.

The Review: Origin stories are a curious phenomenon. It seems you can’t start a comic book franchise without first explaining how characters have obtained their superpowers, as if some justification is required for otherworldly abilities rather than just plain, old fashioned story-telling. The question will always be if these stories are worth telling: no one has yet decided to put pen to paper to attempt to explain whether the Three Little Pigs had endowment or repayment mortgages, or wondered whether The Three Bears sourced the home furnishings that so aggrieved Goldilocks from IKEA or some other home furnishing store. But Sam Raimi has seen a gap in the market: how did the man behind the curtain get behind the curtain in the first place? Is the wizard’s story as compelling as that of Dorothy, or indeed any of the other characters outlined in L. Frank Baum’s fourteen novels based in and around the land of Oz?

As with any venture which calls on well-known or beloved characters, there’s a risk of going too far to either extreme; if you don’t use the existing characters enough, then you’ll alienate the core audience, but fail to include freshness or originality and your purpose will seem false. The restriction that Raimi and Disney had to work under is that Baum’s original novel is now in the public domain, but the original Warner Brothers adaptation from 1939 isn’t, so elements introduced by that adaptation were strictly off limits. This still leaves a pretty open playing field, as long as you don’t want to be wearing ruby slippers (originally silver in the novel), but since this is the wizard’s story, not Dorothy’s, there’s less conflict than you might think. Some excised or ignored elements from the source do make an appearance here, including a land made of china cheekily renamed Chinatown – but this prequel errs on the side of the familiar rather than the fresh.

Indeed, some of the performances feel as if they’ve been lifted directly from 1939, not least James Franco’s cheesy, surprisingly lively interpretation of the titular Oz. Franco’s often gravitated to withdrawn, offbeat roles and it’s certainly the latter, if absolutely not the former in this case. His performance might be an acquired taste, but it’s just one of a number of broad turns which include the witches three (Michelle Williams, Rachel Weisz and Mila Kunis) and some motion-capture LOLs from the wizard’s sidekicks (Zach Braff and Joey King) that stop just short of pantomime. The overall feel is very much in the same vein as Tim Burton’s recent Alice In Wonderland, from the neon brightness of much of the CG backgrounds to the typical Danny Elfman score, but with Raimi, as he so often did with the Spider-Man films, just occasionally adding his own specific flourishes.

What unfolds over the slightly bloated two hour plus running time can be broadly broken down into three phases; the opening twenty minutes, shot as the original Oz was in black and white before unleashing the colour, and featuring some faces of the key players in both narratives; then the tornado lifts Oz and his balloon and it’s practically a theme park ride until Oz encounters other characters in what at first appears to be a sparsely populated land; and finally we settle into the actual story, where Oz looks to understand who he really is. If that sounds like the sort of hackneyed moral that normally underpins middle of the road animation, then it absolutely is, but the gentle humour and the simple characters actually serve to elevate it. It’s hardly revolutionary, but there’s a certain amount of charm in watching how the various elements of the original story fall into place, and while it can’t compare to the 1939 Wizard adventure (or indeed, even the dark charms and originality of the almost cult classic Eighties sequel Return To Oz, which did a better job of drawing on the source material), it’s an entertaining ride that just about justifies its existence.

Why see it at the cinema: Raimi goes big on the visuals and throws in a few trademarks, including POV shots, and there’s no shortage of spectacle or detail, all of which make this a worthwhile experience to make the trip out for.

Why see it in 3D: You’ll notice that the title of this review doesn’t have a “3D” suffix as I saw it in 2D, but I’m going to strongly recommend that you see it in 3D if you can based on what I saw. Not only does Raimi have a good go at two different styles of 3D, including the waving-stuff-in-your-face and also the layered perspective mastered so well by Ang Lee in last year’s Life Of Pi, but seemingly to compensate for the brightness issues of 3D the day-glo aspects have been ramped up, and there were a couple of scenes which cut from darkness to bright sunshine quickly which caused my corneas to attempt to retreat into the back of my head. Even now, the next day, I think there may be images of flying baboons seared onto my retinas, so if you can see this wearing sunglasses – frankly in 2D or 3D – I’d suggest it’s the better option.

What about the rating? Rated PG for mild fantasy threat. The key line is in the BBFC’s extended classification info, where it states that “a PG film should not disturb a child aged around eight or older.” I would just advise a little caution if taking children younger than that, as it’s an occasionally dark film that might trouble the very young.

My cinema experience: Saw this at the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds, where I was instantly plied with chocolate – a combination of a two for £4 offer on bags of chocolate and our Unlimited Premium discounts meant I got a large bag of Maltesers for effectively 75p – and a sparse and talkative audience thankfully seemed unfazed by the first twenty minutes being in black and white, Academy ratio. (I know at least one other Cineworld has been tweeting this out regularly to try to avoid complaints.)

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Tidy. Just three trailers and a meagre selection of public service announcements meant that it was a mere 21 minutes between advertised start time and actual film start time.

The Score: 7/10

Review: A Good Day To Die Hard

The Pitch: Hope That I Die Hard Before I Get Old. (Ah, too late.)

The Pitch: Hope That I Die Hard Before I Get Old. (Ah, too late.)

The Review: Alchemists have tried and failed for all of human history to find a way of converting base metals into gold. For all of our understanding of elements and their combinations driven by thousands of years of science, that understanding has not driven a way to be able to produce quality from just anything, and the same can be said for films. Somehow the Die Hard franchise produced what’s seen by many as the gold standard of action movies, a standard that has endured to this day and a series which has produced varying quality but never truly disappointed. Until now. I’m not going to beat about the bush, A Good Day To Die Hard is dreadful on almost every conceivable level; the only mystery is how a formula which seemed to be the alchemist’s dream, almost impossible to get wrong, has been so badly handled by Skip Woods, John Moore and Bruce Willis.

Let’s take each of the main culprits in turn. First of all, a hallmark of the Die Hard series has been their ability to handle an action scene, with previous directors John McTiernan, Renny Harlin and even Len Wiseman all knowing where to put the camera, how to frame the shots for maximum impact and how to generate pace and tension. John Moore has none of these skills and the action scenes are bland and repetitious. The crucial failing seems to be confusing John McClane with The Terminator, for while the previous four films all understood how to show a man bravely / stupidly venturing into unlikely situations, and occasionally barrelling head first into stupidity, here McClane rampages around in a manner that would make a T-1000 malfunction. Consequently any possible sense of drama or tension has evaporated before we even reach the halfway mark, and the majority of the running time is a procession of dull, repetitive stunt work – McClane gets attacked by a helicopter shooting at a building not once, but twice.

Writer Skip Woods hasn’t exactly given him a lot to work with. This fifth dying of the hard variety is unique in the sense it was written as a Die Hard film, rather than being retooled from an existing script, and on this evidence that was a worse idea than diving off a building tied to a fire hose or driving a car into a helicopter. I could reel off all of the elements that should have made the script and didn’t – and we’re talking fundamentals like a plot, decent bad guys and some form of development for the man always in the wrong place at the wrong time – but it’s just a shame someone didn’t do that for Woods before he fired up his laptop. The Die Hards have always managed to work up a reasonable amount of intrigue and get McClane to do some actual police work, but here he stumbles around blindly in search of narrative and here has less luck finding story here than he normally has finding trouble.

The Die Hards have always had a fantastic array of supporting characters, blessed with both quality and depth and helping to underpin the world-weariness and warmth in McClane’s character. Take away that quality and depth and Bruce Willis just appears bored and shouty, and if the bad guys had a nanogram of charisma between them you’d be rooting for them instead. Everyone seems to think that you throw another McClane into the mix and that’s enough, but Jai Courtney and Bruce Willis have zero family chemistry, and by the time of the ill-advised excursion to Chernobyl – where science and logic bid a sad farewell to all participants – the end can’t come quickly enough. Whatever the recipe was here, the previously golden Die Hard series has been turned to something browner and much more leaden. Something in me feels that, if I’d put my mind to it, I could have been much more insulting about AGDTDH, but if no-one involved with the film can be bothered, why should I?

Why see it at the cinema: You’d be better off blindfolding yourself, then beating yourself over the head with a piece of wood with a blunt nail in it. Not only will it be less painful, but the fact that sometimes you’ll hit yourself with the nail and sometimes you won’t adds a variety and sense of danger that A Good Day To Die Hard is sorely lacking.

What about the rating? Rated 12A for strong language and moderate action violence. The big controversy here, if you didn’t somehow hear about it being ranted extensively on Twitter and blogs the length and breadth of the country, is that the US got an R-rated version (broadly equivalent to our 15) and we got the neutered, less mother abusing 12A version. Anyone that thinks this was (a) anything other than a desperate ploy to feel a steaming pile of detritus to the masses, and (b) denying us a much higher quality 15-rated film based on extra swearing and blood sprays, is as wrong as everyone involved in the making of this sorry pile.

My cinema experience: I sat in a cinema hating myself and everyone involved in this for an hour and a half. (It was the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds.) I’d only gone to see it in an effort to truly compare the efforts of the new Arnie, Sly and Bruce movies; Arnie wins this one hands down. Two people claimed to have enjoyed themselves as I heard them talking on the way out; they desperately need higher standards, and it made me pine for the feeling I had about Die Hard 4.0 at the same cinema. At least the cinema suffered no sound or projection issues, but for a first weekend Saturday evening showing it was a desperately thin and uninvolved audience.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Thankfully the experience was only prefaced by twenty minutes of ads, trailers and the other usual guff, meaning the agony wasn’t prolonged for too long.

The Score: 2/10

Review: Hitchcock

The Pitch: Sasha Gervasi Presents. (Doesn’t have the same ring, does it?)

The Pitch: Sasha Gervasi Presents. (Doesn’t have the same ring, does it?)

The Review: Good evening. I have for you tonight a devious little entertainment, which will shock and surprise you in ways you weren’t expecting. It’s the story of a man who took delight in the more unpleasant side of life and the relationship between men and women, and how the story of a serial killer tortured him to the point of madness. It’s a tale of love, hate, commitment and betrayal, but you’ll be truly terrified by the leading man and what he’s capable of; or should I say, what he’s not capable of? You might think you’ve heard this story before, even very recently, and you probably have, but what’s more likely to keep you guessing than a story that plays out exactly as you think it will? If you know your history, especially your history of Psychos, then you may think that you know the ending, where a film becomes highly successful but also highly notorious, and with a legacy of not only most mainstream horror movies produced since, but also smaller moments which would prove pivotal. But of course, you don’t know this story at all.

Right, enough of the double talk, Hitchcock himself wouldn’t have been a fan of such obfuscation. This is a man that made a trailer for Psycho by walking round the set and all but giving away the main plot points in every location, never spoiling but teasing to the point of genius. This is a man who was extremely aware of not only his own self-image but the need for good marketing to support a good product, a combination never more completely brought together than in the marketing and production of Psycho, certainly not his best film but perhaps his most notorious (and from a man that made Notorious, that’s no mean feat). This is a man who looks nothing like Anthony Hopkins in a fat suit doing an intermittent accent, but at least they got the infamous silhouette correct; George Clooney looks about as much like the real Alma Reville as Helen Mirren does. But it’s a man who would, I’m sure, not have approved of the straightforward nature and simple moralising of his own biopic; we should maybe just be thankful that it’s not the same hatchet job that the BBC’s TV movie The Girl turned out to be just a couple of months earlier.

So what works? Taken as a drama on its own terms, and putting aside any association with its subject matter, Hitchcock is passably interesting as an effective period piece or a TV movie of the week. It might be cookie-cutter drama with simple characters, but it has a timeless quality and uses simple themes well. Some of the minor casting is also eerily effective, with James D’Arcy an uncanny double of Anthony Perkins and Scarlett Johansson actually not a million miles away from Janet Leigh, at least in comparison to the leads. The likes of Danny Huston also turn up and do what they do best in less familiar roles. And again, if you disassociate yourself from the source material, the performances of Hopkins and Mirren aren’t bad, they’re just not particularly representative of their real life counterparts in either appearance, mannerism or character from all of the available evidence.

That’s balanced out by the list of what doesn’t work, and it’s not a short list. On top of the failure of Hopkins and Mirren to inhabit their real life counterparts, its attempts to act as a primer on the making of Psycho are muddied at best, and some moments – such as when Hitch and “Bernie” Herrmann are discussing the merits of scoring the key shower scene or leaving it silent – simply don’t work in the context of the drama. Worse still, there’s a consistent device where Hitch interacts with Ed Gein, real life killer on whose exploits Psych was based, which not only undercuts matters further but implies consequences of screen violence that patently aren’t true, selling Hitchcock’s real life’s intentions painfully short. Many of the supporting characters are cyphers and plot devices, and when it’s all over it’s not particularly clear what it was trying to achieve, a feat clearly at odds with how Hitch constructed his own pointed narratives. Even the opening and closing appearances of Hitch talking to camera, in the manner of the “Alfred Hitchcock Presents…” TV Series with their famous Gounoud theme music playing into Danny Elfman’s anonymous score, are more jovial than the dry intros of the master himself in that series. It would seem the best way to learn about Psycho, and the power of cinema itself, is just to rewatch Psycho. It will certainly be, if you’re much like me, a lot more enjoyable. Until the next time, good night.

Why see it at the cinema: The real Hitch would no doubt approve of you being summoned to the cinema, it’s just a shame that what’s been served up is so utterly lacking in its own cinematic aspirations.

What about the rating? Rated 12A for moderate horror, threat and sex references. Most of the material that made Psycho a 15 rating is merely hinted at here, but it’s not one I’d be taking younger children to.

My cinema experience: A weekday afternoon at the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds, and a largely uneventful screening passed off among a small audience. Not for the first time at Bury, the curtains which wound back before the start of the main feature sounded like they could do with a good oiling. Remind me and next time I’ll bring the WD40.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Hideous. Five full length trailers, adverts and a host of PSAs (including the one from Hitchcock itself with good ol’ Hitch advising you to turn off your mobiles) meaning that the BBFC title card came up for the start of the film thirty-one minutes after the advertised start time.

The Score: 5/10

Review: Wreck-it Ralph 3D

The Pitch: Ralph’s not bad, he just spawned that way.

The Pitch: Ralph’s not bad, he just spawned that way.

The Review: Video games have evolved from a curiosity in a small black box controlling two lines and a small blob to photorealistic depictions of carnage and wanton destruction, an evolution that’s happened in barely two generations. With that evolution, a host of memorable characters have come and gone, then come again in sequels, living on in homes across the world. Once upon a time, in that first generation, the majority of those games could only be played in arcades by handing over small change for 8-bit thrills, where now the arcades are almost as forgotten as the games that we played in them, at least in this country. But they do still exist, and imagine if you will an arcade where simple but classic gameplay is enough to keep you plugged in while other lesser games get taken off to that big arcade in the sky. Would the characters in those games be fulfilled with their lot after thirty years of cycling through the same repetitive actions, or would they long to break their programming – especially the bad guys?

Wreck-It Ralph takes the world of video games and applies a similar logic to that of Toy Story, even though Ralph has been in development in some form since the days when 8-bit was still the standard, rather than retro chic. It’s a world where good and bad are cast in stone in the world we see, but when we’re not looking those collections of pixels can travel down the power cables and visit each other’s worlds. Ralph (John C. Reilly) would be happy in his own game if he got a little more recognition for his work as a wrecker, rather than being forced to spend the night on the garbage heap of bricks while Fix-It Felix and the other game characters spend their nights in comfort and Felix gets all the adulation. Despite the Bad-Anon group of bad guys attempting to tell him he’s a Bad Guy, not a bad guy, Ralph can’t shake the feeling that he’s really capable of more, and sets off to the Hero’s Duty and Sugar Rush games to try to find his purpose. In Sugar Rush he encounters outcast Vanellope (Sarah Silverman), but Ralph’s adventures might have dire consequences for both his game and the others.

Where Wreck-It Ralph struggles compared to the likes of Toy Story is in the simplicity of its conceit. On the surface it’s just “video games come to life” instead of toys, but this is a world with more boundaries and where more rules need to be created to engineer jeopardy for the characters. While the set-up is initially complicated, it’s eased by the front-loading of characters from real-life video games – you know what I mean – so that the majority of the running time is actually focused on those characters invented for the film itself. The two leads, Reilly and Silverman, are both great, continuing a long standing Disney (and Pixar) tradition of good voice casting, and they’re rounded out by a diverse supporting roster which features the likes of Jane Lynch – admittedly delivering the same sort of patter that will be familiar to fans of her Sue Sylvester from Glee, except with slightly less offensiveness – and Alan Tudyk as the king of the Sugar Rush world, seemingly channelling Uncle Albert from Mary Poppins. But a spoonful of oddness helps this medicine go down quite nicely, and the cameos never serve as too much of a distraction; if youngsters have for some reason never heard of Pac-Man or Q-Bert, they should still get the joke.

Where Wreck-It Ralph succeeds in spades is in almost every other aspect. Once you get over the slightly complex rules of the world in which we’re set, then the story works splendidly, with satisfying twists and turns in the narrative which still allow those of all ages to keep up. Ralph’s dilemmas, about his behaviour and his perception to others, are easily to relate to and there’s a good gender balance once Vanellope is thrown into the mix too. Toy Story proves another good reference point, for while I wasn’t brought to actual tears as the second and third Pixar efforts from that series managed, I was still quietly emotional by the action-packed climax and Ralph overall will satisfy both parents and children alike. There was at one point talk of a Sims-like world visit, but it was jettisoned for both narrative and logical reasons, and that care and attention to the through line and the characters will help you warm to Ralph, Felix and their friends greatly. There’s talk of using Mario for the sequel; let’s hope that it’s not game over for these characters for a while yet.

Why see it at the cinema: It’s a riot of colour and sound and the wideness of the cinema screen will allow you spot all of the minor cameos from lesser video game characters. Plenty of laughs for the whole family will also work better with a big audience.

Why see it in 3D: The 3D is just an add-on, and doesn’t really add a huge amount, but apart from the normal issues around brightness and glasses, doesn’t really detract much either. Take your pick.

What about the rating: Rated PG for mild violence. That’s a fair enough rating, given that it’s effectively excluding only the youngest of children.

My cinema experience: Saw this at the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds at an early evening screening on a Saturday; consequently it wasn’t full to bursting by any means. This enabled me to get a fairly central seat (ideal for 3D to minimise the ghosting effect), and a generally well behaved audience saw a screening with no noticeable projection issues, other than it being in 3D. The one point of note was that, after a week of being told my old Unlimited card would no longer work in their machines, I got both a ticket and my evening meal of choice (large hot dog combo and a small Ben & Jerry’s – dinner of champions) by swiping the card with no problems at all.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: A tidy twenty minutes of ads and trailers. Just right to keep kids of all ages happy.

The Score: 8/10

Review: Bullet To The Head

The Review: When you think of the name Sylvester Stallone, it invariably conjures up some of the greater, more hard-edged action movies of the last forty years. Yes, it’s been 37 years since Rocky and 31 since First Blood, and in that time Stallone has knocked out pretty much an action movie or hard-edged drama per year. No doubt buoyed on by the fact that contemporaries such as Bruce Willis and Arnold Schwarzenegger have, Governating hiatus aside, kept going at a similar rate Stallone shows no signs of stopping, and some of his more recent work, especially where he’s gotten to reflect on the passing of time, have been well received. But every action hero needs a good script and a good director to elevate their work, and most of the serviceable scripts which would have been ending up in Sly’s mailbox twenty years ago now have Jason Statham’s name and address on them; no doubt a good chunk of the reason why The Stath ended up co-lead in two Expendables movies. But surely when the likes of Walter Hill come knocking, you can breathe a little easier?

When you think of the name Walter Hill, your first instinct might be to feel reassured, until you start to try to recall the good films Hill’s actually been involved in. The Warriors was good, 48 Hours is OK, and I have a strange soft spot for Brewster’s Millions, but after that I’m really struggling. It’s Hill the director that’s under scrutiny here, for he’s taken Alessandro Camon’s screenplay (based in turn on Alexis Nolent’s graphic novel) and attempted to weave it into a suitable vehicle for Stallone. To say it feels like treading over old ground is an understatement; Hill’s long had a fascination with cops and criminals and their various possible permutations, and the combination slung uneasily together here are Sung Kang (best known for the Fast and Furious franchise) as the cop eager to catch the bad guys, and Stallone as a rent-a-hitman with whom he forms an uneasy alliance while they attempt to achieve their mutual goals.

It’s a template that’s been used a thousand times before, so you’d hope that the casting would elevate this above the rest of the genre. Stallone growls through the film with the Italian-American drawl that’s served him so well for that forty year stretch, but Sung Kang is as wet as a dolphin’s bathroom and never makes either a credible ally or competitor for Stallone. The array of bad guys is somewhat varied: Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje invests some interest as the criminal mastermind, but Christian Slater has clearly just taken a pay cheque having fallen on hard times, and why anyone is still casting Jason Momoa in anything where he’s required to talk or act is beyond me, leering through the film with a demented grin and not much else. None of them get anything of note to work from in Camon’s script, which is just join-the-dots plotting and as predictable as tossing a coin with two heads on.

So this is nothing new for either Stallone or Hill, and both have delivered much better examples earlier in their careers. Cliche gets piled on top of cliche, fights and action sequences come and go with little to excite or amuse and the banter is as weak as a baby’s fruit juice. Hill’s direction adds nothing, there’s one of the traditional opening sequences lifted from later in the plot before we flashback to find how events play out (uninspired both in its use and its overuse) and Stallone feels every one of his sixty-odd years. Simply writing about Bullet To The Head feels a chore, mainly because aside from Stallone and Akinnuoye-Agbaje it feels as if I’m putting in more effort than just about anyone else did. Bullet To The Head is as dry as a week old cream cracker and about half as interesting, and maybe it’s time both Stallone and Hill thought about checking out beachfront retirement properties.

Why see it at the cinema: If you want to avoid doing your end of year tax return for just that little bit longer or the paint you were watching has all dried, then give it a go. But there isn’t a single reason why this needs to be seen in a cinema, and hopefully a slow death on DVD awaits.

What about the rating: Rated 15 for strong bloody violence and strong language. In this case, not enough of a recommendation to see the film.

My cinema experience: With my wife on an early shift, I caught this at a Saturday morning showing, along with about two dozen other men of mixed ages at the Cineworld in Bury St. Edmunds, all with seemingly nothing better to do. Again, sound and projection were about on par with the normal Cineworld experience, so the most excitement I saw all morning was when at the ticket stand, my salesperson advised me that as it was still one of the older style Cineworld Unlimited cards, my card had likely been cancelled (it hadn’t) and then promptly sold me a ticket for the wrong showing. That’s the second time this year, at two different Cineworlds, and I’m hoping it doesn’t become a pattern.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Another 22 minutes, which seems to be about the average this year.

The Score: 4/10

Review: The Last Stand

The Pitch: He said he’d be back. It just took a few years…

The Pitch: He said he’d be back. It just took a few years…

The Review: When I started this blog nearly three years ago, it was with an intention to share and express my love of cinema in all its forms. I’ve never considered myself to be much of a writer, but have always hoped that enthusiasm and my increasing knowledge would carry me through. You, dear reader, can continue to be the judge of that, but I’ve always enjoyed a broad church of film and that’s only increased over the past five years. But some things have been missing from the cinema catalogue, thanks to my age and a large number of years when my viewing was restricted to home entertainment. One of the most significant gaps in my viewing experience has been the Austrian Oak, the ultimate action icon of the Eighties and Nineties, and if you discount his selection of cameos from the last decade, I can count two Arnie films I’ve seen in the cinema for the first time: The 6th Day and Eraser. If you had the chance to see either yourself, you have my sympathies, but like me you might just be pining for a great Arnold Schwarzenegger film to show up in cinemas.

The Governator has stopped governating, or whatever it was he was attempting to do to California for most of the last decade, and he’s decided to see out his remaining years doing exactly what he does best: make action movies. You’ll find he’s easing himself in gradually, as he’s only in around half of The Last Stand. The set-up does see a bit of Arnie, looking befuddled while Johnny Knoxville and Luis Guzman clown around in their sleepy backwater on the U.S. / Mexican border, while in the main plot Eduardo Noriega’s highly dangerous criminal gets sprung from his prison transport and slips through the fingers of FBI agent Forest Whitaker. Noriega’s making a run for the border, but it also turns out he’s an illegal but highly experienced racing driver in his spare time (but of course) who’s got a 250 mph supercar and is making a break right for Arnie’s border town, where Peter Stormare and his crew are preparing to spring Noriega over the border when he arrives. As Forest and his FBI chum(p)s repeatedly fail in their attempts to slow down a man so powerful he doesn’t even need to stop for gas when driving half way across southern America, only Arnie, that guy from Jackass and the guy who they built a statue of in Community stand in his way.

I’m not going to pretend The Last Stand is high art, and thankfully for most of its running time neither are the makers of the movie. It’s director Kim Jee-Woon’s first big English language pic, and the director of I Saw The Devil and The Good, The Bad And The Weird knows how to make an action movie. He keeps his camera interesting through everything from the initial break-out to the final showdown (including an innovative chase through a cornfield), but even he can’t wring much originality or tension out of the set-up. Forest Whitaker gets the expository role, and I can’t remember a part he had so thankless since Species – although a few others have come close – and the first hour cuts between his efforts and the incompetent sleuthing of the other hometown police, including Jaimie Alexander and Zack Gilford. It’s all scripting by rote, and starts to tip over into deeply maudlin around the hour mark, as if it needs something to kick it into high gear.

That thing is about 6′ 2″ and built like a leathery tree, and when Arnie finally gets his thing on, the whole film goes up at least two gears in both entertainment and action. The earlier sequences almost feel a cunning ploy, to soften the focus of the background elements while setting up the stakes, so that when the elderly Terminator does arrive it feels all the more impressive. Either way, when it happens, Arnie simply comes in and blows everyone away, driving, punching and blasting through everything in sight like an unstoppable Austrian train. It does acknowledge he’s getting on a bit, briefly, but then proceeds to ignore that and the last act is an orgy of satisfying movie violence and occasionally silly comedy, one where all of Arnie’s team get a reasonable look in. It’s a complete throwback to the action movies Arnold made his name with in the Eighties, and while it’s no Predator or Commando it’s an awful lot better than Eraser or The 6th Day, crucially only taking itself too seriously for one brief, Ahnuld-free stretch in the middle. If you want to just kick back and turn off your brain, you could do a lot worse.

Why see it at the cinema: Hopefully you’ll see it with an audience who all enjoyed the over-the-top elements as much as I did. The poor box office seems to be an indication that audiences would rather illegally download this kind of movie than see it in a cinema; their mistake, don’t make it if you’re a fan and get the chance.

What about the rating? Rated 15 for strong bloody violence and language. As you’d expect – or hope for – from the director of I Saw The Devil. Plenty of blood spray, but it’s more cartoon violence than anything.

My cinema experience: Picked up my ticket from the ticket machine, dodging the reasonable queues at the Sunday afternoon Cineworld in Cambridge, and settled in near the front on the left of a half-full cinema. It appears I picked the wrong half, as all of the raucous laughter and enjoyment was coming from those sat further back on the right hand side; everyone else on my side, with the exception of me, was sat in stony silence for the majority of the running time. I was this close to switching sides… No sound or projection issues.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Twenty-two minutes of promotional activity of the usual form before the film commenced. Just about reasonable.

The Score: 7/10 (probably around a 5 for the bits without Arnie and an 8 with him)

Review: McCullin

The Pitch: Photography: a window to the soul?

The Pitch: Photography: a window to the soul?

The Review: The 20th century brought us cinema, the collective experience of watching moving images and sound projected onto a large screen. Creative minds have used this innovation to dazzle and to amaze with works of improbable fiction, but also to attempt to understand and document the human condition. This particular documentary looks at another form of documentation of the world, but by the use of a single frame rather than a collection of 24 per second. Donald McCullin has been at the forefront of his art for most of the fifty years he’s been pointing his camera at not always willing subjects, and Jacqui and David Morris’s documentary attempts to get to the heart both of what made his work so compelling, but also what drove someone to want to take such images, and to make a career out of it.

The film consists predominantly of interviews with McCullin himself, including an extensive face-to-face interview where McCullin recounts his live story, interspersed with other clips of him being interviewed, including a Seventies interview on Michael Parkinson’s chat show. This recounting of his life story starts with his upbringing in and around east London where he first trained his camera on the other inhabitants, from the destitute to the more unsavoury. This soon got him work with the Observer newspaper, before eventually moving to the Sunday Times where he established his reputation as a supreme photojournalist. In the space of an eighteen year career, he covered many of the world’s major conflicts, from Cyprus to the Congo and Biafra, and from Vietnam to Northern Ireland, and his images sought to uncover the true nature and effects of those conflicts.

Interspersed with the interviews are a selection of McCullin’s images from each period, and what immediately becomes clear is McCullin’s gift for being able to find the perfect moment within each shot. While we only ever see the choicest images from the reels of film taken, without his innate sense of composition and his flair for drama, he’d never be in a position to capture the powerful images shared with us on screen. McCullin looks at both sides of conflict, trying to understand what motivates men to keep fighting – although more interested in the effect than the cause, as witnessed by the image of the shell-shocked soldier seen in the photo above – but he also captured devastating images of suffering, often of children caught up unknowingly in these conflicts. His candour is refreshing but also allows for some alarming insights into how far he’s been willing to go in the name of his art, getting caught up with mercenaries and being shot at regularly enough for the occasional bullet to have found both him and his camera.

If you’ve ever wondered how those taking such images manage to remain passive in the face of such suffering, then the documentary also makes it clear how this worked for Donald McCullin; it didn’t, and often a moving picture would have seen him interceding on behalf of his unfortunate subjects. Some of the images captured are by their very nature brutal, but thanks to McCullin’s need for compassion from the viewer they never feel exploitative, and taken as a whole they form a remarkable body of work of one man keen to expose the true horrors of this world and in some small way hope that the next generation sees this and tries not to repeat the mistakes. Two tiny quibbles: many of the conflicts (such as the Biafran secession from Nigeria in the late Sixties) are explained by means of black and white title cards which barely leave enough time to digest their contents, but this can be forgiven if you overlook them completely and focus on the content of the interviews and the selected photographs. As with any documentary, or indeed photograph, we are forced to accept an element of the truth portrayed to us, and certain occasional facts (such as the reasons why McCullin didn’t travel to the Falklands) may have other interpretations. This also results in a portrayal of McCullin almost as seen through his own eyes, but when they work as well as Donald McCullin’s do, that can be no bad thing.

Why see it at the cinema: Compelling black and white photography, blown up to the size of a cinema screen, is just one reason to catch this in a cinema if you get the chance.

What about the rating? Rated 15 for strong images of injury and real death. There are some image of death I wouldn’t say were out of place in a horror movie, but the black and white photography softens the blow somewhat. But that rating is spot on in my book.

My cinema experience: Arrived at the Cambridge Arts Picturehouse cinema exactly on the advertised start time, which normally allows me to grab my ticket while the adverts are still playing. I’d reckoned without the immense queues for Les Mis, which had caused all three performances to sell out for Saturday. Thankfully you can pick up tickets at the bar, so I took the chance to grab a hot chocolate and my ticket together. The weight of numbers was even causing the coffee machine to groan under the strain, but it just about gurgled me out enough hot milk for a hot chocolate. Screening was half full, pretty impressive for a Saturday lunchtime doc screening, although that may have had to do with the limited number of screening opportunities during the week. Apart from one pair of noisy latecomers, a very civilised audience.

The Corridor Of Uncertainty: Around 15 minutes. Thanks to the queues I arrived around the time of the BBFC title card, so missed the trailers this time round.

The Score: 9/10