2013

Cambridge Film Festival 2013 Day 3: Hannah Arendt, Muscle Shoals

Day 3 arrived, and as usual in the film festival it’s the one day each year when commitments of my other hobby leave me unavailable. But for a humble church chorister as myself, the chance to sing in King’s College Chapel each year is too good to turn down.

The difficulty of this is that it means almost a whole day when I can’t see films. With an impeccable lack of timing, the film that won the audience award screened in this slot in 2012. Last year, because I’m clearly insane, I went to Bums On Seats for the first time, then to a film, then to sing at King’s, then back to the cinema for more films, and still managed to miss the festival’s best. I was Bumming again this year, venting my Hawking frustrations again (which you can hear here) but sadly there was no suitable gap before the evening to get a film in.

So after singing until I was hoarse, my first film of the day was Hannah Arendt. I have a passing interest in philosophy, so Hannah Arendt’s name is one of those I’ve heard of but couldn’t necessarily place. Arendt was a chain-smoking free thinker who saw her theories taking precedence over the feelings of friends and colleagues. This might not have been so provocative had Arendt’s theories not centred around the motivations of the Nazi. Arendt was herself a Jew who’d escaped a French detention camp, but she’d also had an affair before her marriage with a Nazi-sympathising professor and some couldn’t see past that when reviewing her work.

There’s a disconnect at play, in that emotions and passions are suggested to be running high by Hannah’s actions, but that’s barely alluded to on screen. The footage from Adolf Eichmann’s trial shows great anger, but that level of emotion never translates into any of the film’s contemporary characters. Hannah Arendt builds to a simultaneously thoughtful and stirring climax, but it’s a shame about some of what precedes it.

I also reviewed the film for Take One in more detail here.

Muscle Shoals

There’s been some superb music documentaries in the past few years, but the best understand the balance between the music and the story behind it. Muscle Shoals has a phenomenal musical heritage to call on, and the talking heads make a line-up that would make Glastonbury blush, from Alicia Keys to The Rolling Stones and Wilson Pickett to Aretha Franklin. The music is unquestionably the highlight, and what Muscle Shoals does well is to not only give insight into the characters behind the music, such as Rick Hall, but into the process and composition of the sound. It tells the story of how both Rick Hall’s Fame Studios and its rival Muscle Shoals Sounds came into being, and in the process left its distinctive sound written through decades of music like letters in a musical stick of rock.

The only area where Muscle Shoals falls down slightly is in an attempt to be a comprehensive and exhaustive history of the musical period, following a fairly strict chronology. By the time we’re into Lynnyrd Skynnyrd the fascination may be waning somewhat, and trimming 10-15 minutes may have helped. It’s a documentary that looks almost good as it sounds, the digital cinematography showing off both the countryside and the crags in Keith Richards’ face to equal effect, but it’s at it’s best when it’s exploring the characters behind the music.

Cambridge Film Festival 2013 Day 2: Mushrooming, Particle Fever, The Crash Reel

As I mentioned in my coverage of Day 1, after three years of being solely a paying punter taking in the festival has escalated somewhat and I am now involved in a whole range of media coverage. Day 2 saw me take the first steps on two particular journeys as part of that coverage.

The other thing that Day 1 had brought was some unexpected recognition of my behind the scenes support, as part of a cast of dozens that help to make the festival what it is. While my contribution was fairly minimal compared to some of those that work full time for much of the year to bring these eleven days of cinematic heaven to the public each year, everyone is equally rewarded when it comes to thanking those involved, and a giant caption displayed before each film lists the names of those involved. The past year of my involvement in film activity in and around Cambridge means that a significant proportion of these names are now people I know and talk to regularly, and it’s had the effect of making the festival that much more interactive, and even more enjoyable for a fledgling film geek like myself.

In fact, I was so thrilled to see my name in lights that I hadn’t noticed something about it:

That’s my name, at the top of the third column. It took me two films to notice that my name was spelled wrong. But hey, there’s no wrong letters, just a slight absence of all of the rights ones, and I’m a firm believer in that it’s the thought that counts.

So my first involvement of the day was to introduce the film Mushrooming, then to host the Q & A afterwards. Actor Raivo E. Tamm had been brought over by the Estonian embassy especially for the film’s two screenings, and I headed down to introduce him and the film, having seen a screener of it already. Arriving at the microphone, I got right into the line of the projector and promptly blinded myself, causing me to give a rather panicked introduction. Raivo stayed in for the duration of the film, allowing me to pop out and continue to prep for my questions later. Q & A sessions can sometimes be difficult to judge, as you never know quite how many questions are going to come up. In the end I asked two or three lead in questions, and then left the rest to an audience seemingly keen to know more about the actual practice of Mushrooming.

The film itself played after a whole Estonian season last year (including Raivo as Disgruntled Tennis Player in The Temptation Of St. Tony) and Raivo backed up the fact that Estonian cinema appears to be attempting to be a little less deep and ponderous. Mushrooming starts out quite dry, but gradually blends its genres until a simple trip into the woods for a politician and his wife escalates into a stand-off in a cabin with a redneck and a rock star. It’s played generally very straight, and consequently it might not be for everyone, but you must be doing something right if you can be simultaneously over the top and understated. (And Raivo’s the best thing in it, even if I had to concentrate extraordinarily hard at all times not to call him Ravio.)

It feels odd watching a physics documentary in Cambridge. Twenty years ago I was turned down here for a place reading mathematics after I had two interviews. The physics one went so badly I couldn’t remember Newton’s three laws, so I felt slightly uncomfortable sitting in an audience potentially filled with some fine academic minds. I needn’t have worried; Particle Fever gets the balance just right between the human stories of the CERN project at the Large Hadron Collider and giving a sense of the magnitude of the potential consequences of the discoveries being made for the very future of science itself. The editing by science buff and not-bad-editor-either Walter Murch helps to condense the four year story into a digestible narrative with clear direction, but it’s the graphics from design firm D12 (also responsible for Quantum Of Solace’s opening credits, fact fans) that help to make the science digestible. Mark Levinson’s project is clearly one of passion and is far more likely to inspire people to an interest in physics than day 1’s Hawking documentary.

This was also my first review for Take One, Cambridge’s independent film magazine which runs along side the festival. The full review can be found here.

We have become so inured to the sight of extreme sportsmen at events such as the X-Games pulling off their tricks that the element of spectacle can be somewhat diminished, driving the sportsmen themselves to attempt even greater stunts for our gratification. We’re also so accustomed to seeing the stunts not quite come off that when champion snowboarder Kevin Pearce comes a cropper at the start of this documentary, just six weeks before the Olympics, we’d naturally expect him to dust himself off and for this to be a story of triumph over adversity. But The Crash Reel is something very different, and so much more powerful for it.

Kevin suffers a traumatic brain injury (TBI), and Lucy Walker’s documentary charts his path to attempted recovery, alongside the strain it’s put on his close-knit family and especially two of his brothers, one of whom suffers from Down’s Syndrome. The Crash Reel is both a gripping human drama and a damning indictment of the nature of extreme sports. Walker has struck documentary gold with her subjects and makes the most of what she’s been given, and has assembled a documentary that will traumatise and appal you in the best ways possible, but if there’s any justice in the world should be a catalyst for change in these fledgling sports. Just occasionally the onscreen graphics feel a little overdone as Walker attempts to keep on top of her characters, but other than that it’s hard to find a flaw, and hopefully this will find a wider market than just snowboarding geeks; I for one felt physically affected by it.

Cambridge Film Festival 2013 Day 1: Just Before Losing Everything, Life Distorted shorts, Hawking, Prince Avalanche

This is my fourth Cambridge Film Festival, which I first encouraged myself to explore after starting this blog in 2010, and this year by the morning of the first day I had a palpable sense of excitement for what was coming up. Partly that’s my involvement, which this year is reaching new levels: as well as a daily diary here, I’m also contributing a number of interviews to Take One, the Cambridge publication that runs alongside the festival, and hosting two Q & A sessions. For me it’s a thrill to be involved, but also serves to further the reason for setting up this blog originally, to attempt to get word out about the finest films showing anywhere and to encourage people to see them, and my evangelising will reach new heights over the next eleven days.

The first day is always a slightly strange experience as it’s really a half day, with films typically starting late afternoon before the gala opening. I’ve had good experiences with the opening films, as in 2010 (Winter’s Bone) and 2011 (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy), the first film I saw each year was also my favourite come the end of the festival. (Last year was the opposite experience, with my favourite two films being the last I saw.)

But this year also marked a personal milestone, in that on day one I finally managed to get to a short film programme. I’ve taken in Tridentfest for the last two years, but for externally submitted films I’ve had tickets and then had to return them for various reasons. So it was a joy to finally be able to take in a selection of shorts, and I’m hoping I’ll get more chances throughout the festival.

Here’s my breakdown of the good, the strange and the desperately unfortunate that made up day 1.

This French short, running to around 25 minutes, is showing in conjunction with a number of other shorts programmes over the course of the festival. It’s difficult to get too much into plot without giving the game away, but there’s a number of sharp and sudden escalations in the plot and the viewer is left to piece together what’s happened from pieces of conversation and visual clues. By effectively stripping out any exposition and allowing the plot to drive the narrative, Just Before Losing Everything builds and maintains tension almost out of nowhere, while running parallel social commentary, and it perfectly fit the running time. It comes highly recommended if you get another chance during the course of the festival.

Life Distorted

What followed was the first of the festival’s half a dozen or so short film programmes that will run during the course of the festival, in this case seven films which each had a somewhat skewed outlook on life. Personal highlights included Our Name Is Michael Morgan, a tale of competition between two eerily similar salesmen, and Emmeline, the tale of a girl who has to overcome an unusual affliction to find happiness. Director Tim Hewitt was also in attendance for his adaptation of a Graham Greene short story A Little Place Off The Edgeware Road, and the thread also included the voiceover difficulties of A Big Deal, the a satnav with jealousy issues in Bird In A Box, the short and slightly macabre animation Menu and the tale of extreme recluse author Izzy Blue in Hermit. Overall there wasn’t a significantly weak link, and with two or three charming and provoking shorts this was a well composed programme. A slight sound issue on the first film thankfully didn’t cause too many problems.

The main event of day 1 was the gala screening of the documentary Hawking with Q & A, which had not only taken over all three screens at the Cambridge Arts Picturehouse but was also being beamed live to cinemas around the country. Demand was certainly high, and five minutes before the scheduled start time I was in a queue that stretched virtually throughout the entire length of the cinema, from the screens doors through the bars and almost to the street.

The documentary they were all served up is a curious beast. Although directed by Stephen Finnegan and Ben Bowie, it’s been co-written by them and Hawking himself. Hawking takes his opportunity to summarise his career achievements, from theories on the Big Bang to his partunification of various fields, but that’s all it is: a fairly thin biography that serves to eulogise its subject without ever getting below the surface. In that sense it achieves its initial aim, as Hawking wrote The Brief History Of Time not only to bring science to the masses, but to encourage the wider questioning of the fundamental aspects of the universe. Consequently, a documentary that doesn’t question anything feels violenty at odds with its subject and his philosophy, and for a pseudo-scientist such as myself it comes over as an exeperiment based on a fundamentally flawed terms of reference.

This was then followed by a question and answer session that can charitably be best described as excruciating. A set of unfortunate circumstances, including Professor Hawking’s seeming movement to the wrong part of the cinema leaving him stuck when it came to his time to answer pre-recorded questions, a failure of his pre-recorded questions to answer, a set of odd questions from a bemused audience who seemingly hadn’t been briefed that they couldn’t answer Hawking any direct questions and Krishnan Guru-Murthy’s insistence on (probably unintentionally) doing his best to draw the audience’s attention to the flaws at any given point, the whole experience was the equivalent of a slow-motion car crash, enlivened only by video messages from Sheldon and Amy from The Big Bang Theory (geekgasm), Richard Branson (space advert) and Morgan Freeman (bizarre non-sequitur). To cap it off, when fellow scientist Kip Thorne was asked where Hawking sits in the scientific pantheon, he gave a very honest answer that still felt somewhat uncomplimentary in an evening desgined to celebrate the world’s most famous scientist. I don’t believe anyone at the cinema or the festival itself to have been too responsible for what happened, and it would be unfortunate if it reflected badly on them.

David Gordon Green’s directorial career has followed a somewhat unusual trajectory, from the inide credibility of George Washington and All The Real Girls to the mainstream excess of Pineapple Express and Your Highness. Pineapple Express represents a meeting of minds of the two David Gordon Greens: Paul Rudd and Emile Hirsch are two highway workers wandering through a wilderness painting lines on the road and putting up posts, while they gently bicker and attempt to resolve the issues with their respective love lives (not least the fact that Rudd is dating Hirsch’s sister and has only taken him on this journey out of a feeling of loyalty). Their relationship is fractious, slightly daft and often laugh-out-loud funny, and if that was all there was to Prince Avalanche it might not be enough. But the wilderness they’re tracking through is one devastated by wildfire and their encounters with some of the other residents of the wilderness add a resonance and a sweetly melancholic tone. It’s also lovely to see a great performance from Lance LeGault, remembered by anyone my age and sensibility as Colonel Decker from The A-Team in what turned out to be one of his last roles; the film is dedicated to his memory. It’s a fine achievement by Green, bittersweet and roughly honest with itself and beautifully shot in the washed out residue of the American wild.

Coming soon: day 2, with my reviews of Mushrooming, Particle Fever and The Crash Reel.

Review: White House Down

The Pitch: Die Hard In The White House.

The Pitch: Die Hard In The White House.

The Review Die Hard Tick List (contains mild, non-specific spoilers):

Why see it at the cinema: If you like big, loud, dumb fun and haven’t seen the White House get blown up enough this year, go for it. Olympus Has Fallen was a strange entity, a serious White House take over movie with a cartoonish Gerard Butler at its centre. Here, Jamie Foxx’s least convincing President ever and James Wood’s shock-haired Secret Service head just make the whole film cartoonish, making the wanton carnage and loss of life at the start sit even more uncomfortably.

What about the rating: Rated 12A for frequent moderate violence and threat, and one use of strong language. Bog standard 12A action movie, which if you take children under 12 to already, you won’t have any increased issues here.

My cinema experience: Proof if any were needed (and it almost certainly wasn’t needed) that you can actually tell the difference between genuine, laughing at the joke laughter and incredulous, “did they really just do that” laughter. There was a small amount of the former and a considerable amount of the latter at the screening I saw at Cambridge Cineworld; both added to the experience, although the sheer amount of audience incredulity may have caused me to knock a mark off. My only grumble was the return of the Corridor Of Uncertainty, that period between the advertised time and when you actually get the film. Cineworld have been pretty good lately, but 27 minutes for a two hour ten action movie felt a bit much.

The Score: 5/10

Previous Die Hard Tick List review:

Review: About Time

The Review: There’s two ways you can travel in time in movies: the bold, brash way to arrive in style, like a modified Delorean (Back To The Future), a massive ball of electrical energy (The Terminator) or an electrified phone booth (Bill and Ted), or there’s the British way, typically through a small dark portal (Time Bandits) or by going to the toilet (FAQ About Time Travel). Richard Curtis’ new time travel film takes this to a new low of British restraint, where Bill Nighy announces to his son Tim (Domnhall Gleason) that men in the family have the ability to travel in time, by standing in a dark place, clenching their fists and concentrating. Now admittedly time travel movies are rarely about the mechanics of time travel itself and more about the implications, but there’s undoubtedly something very British about a method of time travel that could only be more understated and stereotypically British if it involved sighing forlornly while drinking a cup of tea. But time travel movies are two a penny, so the key is to deliver something new with it, and when the likes of Duncan Jones gave us the highly original Source Code two years ago, that’s no easy task. Two years ago… Oh, let’s not start that again. In fact, let’s start again.

[hides in cupboard and clenches fists]

Richard Curtis is the writer of the finest British comedy of the last thirty years. It’s called Blackadder, and I still regard career misanthrope and wrangler of cunning plans Edmund Blackadder as some sort twisted role model. Richard Curtis has also written a story involving time travel that successfully tackled serious issues in a thought provoking manner but still managed to be charming and fluffy, with an awkward leading man who might just be an archetypal British eccentric. It’s called Vincent And The Doctor, an episode of Doctor Who from 2010 that showcased how Curtis can push the boundaries of his own writing if he puts his mind to it. Richard Curtis even co-wrote two episodes of Blackadder that featured some form of time travel (Christmas Carol and Back And Forth), so quite why or how he’s managed to come up with a time travel film that doesn’t do a single original thing with the concept, or feature any significant laughs, is bemusing to say the least. Actually, About Time is more of a comedy drama than a straight-up comedy… Balls, gone wrong again. Do over!

[hides in cupboard and clenches fists]

Anyone reading this blog for any length of time will be aware that I often start my reviews with some form of personal insight as a prelude to my thoughts on the film. With a film such as About Time, that proves somewhat tricky, as the core relationship in the film isn’t actually Tim’s slightly creepy, stalkerish pursuit of Mary (Rachel McAdams), but instead his relationship with his father. Gleason and Nighy don’t exactly have a strong family resemblance – maybe Tim gets more from his mother, Lindsay Duncan, but surely the genetics of that would impact on the time travel? – but as someone whose father divorced his mother at the age of seven and effectively disappeared out of my life (me, not him, obviously), films built on strong father / son relationships are always likely to strike a raw nerve. If I was examining familial relations with time travel, I might not be pulling a McFly and inadvertently wooing my own mother, but I’d love to get more insight into my own father and his particular motivations, but that doesn’t interest Richard Curtis either. Not sure where I’m going with this. Bugger. One more try.

[hides in cupboard and clenches fists]

So I’ve now got one paragraph left to tell you about Richard Curtis’ film About Time, starring Domnhall Gleason, Rachel McAdams and Bill Nighy. Gleason is one of those British actors who has managed to do brilliant work on the periphery of some quality films in the past few years (Dredd, Never Let Me Go, True Grit, Anna Karenina and even a couple of Harry Potters) but comes into his own here, producing a warmer and more likeable Curtis lead than even Hugh Grant ever managed, but with that same bumbling awkwardness that’s quintessentially Curtis. In fact, almost every trope and plot point of About Time is very Curtisian, that British middle-class state that exists in Curtis’s films and almost nowhere else. What this has done is to have matured slightly, both in world view and in the quality of the production, feeling less staged and noticeably warmed by the presence of its three leads. It feels like a Richard Curtis film that’s trying not to look like a Richard Curtis film, but paradoxically ends up being about as clear an example of the genre as film Curtis has made. It’s a warm comfort blanket of a film, and if you’ve overdosed already on the saccharine output of Mr Curtis over the years then this won’t win you over, but if you’re looking to be cinematically cuddled rather than challenged then this has arrived in the nick of time.

Why see it at the cinema: It’s Curtis’ best looking film to date in respect of both cinematography and the charmingly cute appeal of his cast. Yes, even Bill Nighy.

What about the rating: Rated 12A for infrequent strong language and moderate sex references. Slight issue here. We’re averaging around one “f***” every twenty-five minutes, pushing the boundaries of what’s acceptable to accompanied children under 12. Said children will also get repeated shots of Rachel McAdams in her bra and knickers and an extended, enthusiastic sex scene. I would be uncomfortable taking younger children to see this, because I’m a middle class prude who’s not as liberal as he’d like to be, but I personally would have put this at 15.

My cinema experience: Seen at a Cineworld Unlimited preview evening in Bury St. Edmunds, and after a showing of 2 Guns the previous week was full, I was surprised to see About Time with spaces in the audience. (Maybe it was too early for word of mouth to have built.) Lots of generally middle-class tittering but no huge laughs for the audience, who were also spared any projection or sound issues.

The Score: 7/10

Review: Rush

The Review: Formula One. Outside of America and its Indycar obsession, it’s still regarded as the pinnacle of four wheel vehicular competition, commanding global audiences of around half a billion people a year and generating enough sponsorship and investment to make your eyes water. What it’s often lacking in is drama, especially as Sebastian Vettel’s dominance this season has left his rivals trailing in his wake. To someone like me who’s not a passionate fan, it feels a sport that’s become more about the machines than the men, and somehow the sense of drama that should exist when six of the last ten competitions haven’t been settled until the final race has been lost (and especially when in five of those six, the final winning margin was four points or less). Watching the 2011 documentary Senna now feels like a lost era with its fierce competitive rivalry between Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost the stuff of half-forgotten legend. For those that can cast their minds back a few years further, they may remember a similarly close battle from 1976 between English playboy James Hunt and his Austrian rival Niki Lauda.

Chris Hemsworth portrays James Hunt with all the swagger of a man who’s made a career playing an over-confident demigod, but that in itself may be a just and true analogy for the perception racing drivers have of themselves. We see Hunt battered and bruised initially, not from racing injuries but from the attentions of a jealous husband, and Hunt even manages to get his end away before he’s left the hospital. Rush tracks his gradual rise from the petrolhead larks and raw ambition of Formula Three in the early seventies to his entry to Formula One and his battle to get a seat in a car worthy of his perception of his own talents. His story is told in parallel with that of Lauda (Daniel Brühl), who similarly rebels against his upbringing to fulfil his high octane dreams. Where Hunt is the loose cannon getting by on raw talent and rough-edged charm, Lauda is the technical genius who gets his edge from tuning the cars, but has a more clearly defined concept of acceptable risk in one of the world’s most dangerous sports. The film starts with a flash forward to the pivotal moment of their most heated battles, the 1976 Championship, and the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring where the debate over risk came to a potentially deadly head.

Hemsworth and Brühl dominate the screen and the film, Hunt’s golden locks and cheesy grin the perfect counterpoint to Lauda’s mousy overbite and personality deficiencies. Hunt sees the world and Formula One as much as a popularity contest and is in it for fortune and glory, Lauda sees the thrill of the chase and the challenge of competition but the similarities are clearly and obviously laid out. Hemsworth and Brühl are both excellent, and backed up by an eclectic supporting cast which seems to have been drawn from a mixture of the Green Wing casting director’s little black book (Stephen Mangan and Julian Rhind-Tutt being two of Hunt’s crews over the years). The other notable roles are the women in the lives of the two drivers: Alexandra Maria Lara provides a soft yet believable counterpoint to Lauda’s brusqueness, while Olivia Wilde is almost unrecognisable with a well-tuned English accent and blond hair as Hunt’s upper class marriage of convenience. As with director Ron Howard’s previous factual collaboration with writer Peter Morgan, Frost / Nixon, the performances steer the right side of caricature and serve to sell the drama.

The real strength of Rush lies, initially surprisingly, in Ron Howard’s depiction of motor racing, which captures the globe-trotting breadth and lavishness of the sport, even in the Seventies, but also puts tension and excitement into every overtaking manoeuvre and clash of wheels, and uses the internal mechanics of the cars and engines to create a throbbing pulse to help raise the heart rate. Howard has previously shown a gift for grand scale drama and nerve shredding tension with Apollo 13 and many of the key moments of Rush are no less effective. Having engaged your senses, when the real drama comes it it emotionally affecting, but that’s despite Peter Morgan’s script, not because of it, Morgan’s lumpy cliches feeling wrong coming from the mouths of drivers rather than politicians or journalists. Every good racing team is backed up by a good pit crew, and if Morgan lets the side down somewhat then it’s more than made up for by the cinematography of Danny Boyle regular Anthony Dod Mantle and composer Hans Zimmer who elevate even the most mundane moments of the pit lane. The unfortunate conclusion it’s tempting to draw from comparing this to modern Formula One is that a part of the thrill of earlier racing was that almost ghoulish thrill of the possibility that each driver’s race might be their last, which commendable standards of modern safety have somewhat compromised. Whether you subscribe to that view or not, Rush provides the same thrills of the best of real sport, safe in the knowledge that no actors were harmed in the making of this movie.

Why see it at the cinema: Ron Howard’s managed to take something which can be as dull as dishwater on TV, and create a sense of excitement not only from narrative twists but from the visceral thrill of delicate and overpowered machines careering round corners and jostling for position, and you couldn’t ask for a better depiction of the sport on the big screen. Find somewhere with a decent sound system as well, to get the most from the growl of the engines and Hans Zimmer’s typically bold score.

What about the rating? Rated 15 for strong language, sex and bloody injury detail. A fair rating, but fans of casual nudity and / or Chris Hemsworth won’t be disappointed.

My cinema experience: The joys of screen 9 at my local Cineworld in Cambridge. Quite often I’m perched on the end of rows, for one of two reasons: either I’ve taken Mrs Evangelist, and she inevitably has to factor in a comfort break so being on the end is convenient, but even on my own I’m almost six foot three and I’m not easily accommodated for leg room. Screen 9, however, is the largest at that particular Cineworld and one of the few cinemas where I can sit in the middle of a row and still have ample legroom. A decent sized crowd on a Saturday lunchtime all seemed to come away having enjoyed themselves.

The Score: 8/10

The Half Dozen: 6 Most Interesting Looking Trailers For September 2013

Okay then, So this time last month, I was posting up a list of my six trailers for August, and was merely a humble blogger. One month later and I appear to be well on the way to a full-blown activist and campaigner. In case you missed it (and if you did – WHERE WERE YOU?!), the Competition Commission announced plans to compel CIneworld group to sell either Cineworlds or Picturehouses near to where I live, I wrote a 5,000 word rant spread over two days based on the fallacy of the decision as I perceived it, and then went on to start a petition that’s had 12,000 signatures in a couple of weeks (thanks to the efforts of all those valiantly spreading the word on its behalf). You could say it’s been an interesting month.

But I believe in fighting for what’s important in life, and to me cinema has become one of my great loves over the past few years. Even with the cinemas close to me, it’s difficult to find all of the films on offer; a rifle through any of the main film publications of our time will list reviews of films on release anywhere in the country, but actually tracking down showings of these can sometimes prove troublesome. I’ve got twenty-five multiplex screens and five art house screens within half an hour’s drive, and they show a wide variety of films, but even they can’t manage to get everything when the multiplexes are replicating their content so heavily.

So this month I’ve picked out six films that anyone picking up a copy of Empire or Total Film might read the review of and think of popping to their local cinemaplex to catch, but in my case each would require a one way trip of the length outlined below just to catch the film. (I have made trips of this length before on occasion, but with the Cambridge Film Festival just a week away I’m going to be sticking a little closer to home for now.)

No One Lives

Nearest showing: Leicester Square

Travel time: 1 hour 29 minutes

Any Day Now

Nearest showing: Dalston

Travel time: 1 hour 20 minutes

42

Nearest showing: Enfield

Travel time: 1 hour 12 minutes

Museum Hours

Nearest showing: Ipswich

Travel time: 55 minutes

In A World…

Nearest showing: Stevenage

Travel time: 55 minutes

Pieta

Nearest showing: Ipswich

Travel time: 55 minutes

Competition Commission: Why We Can’t Afford To Lose Cineworld Either

Nearly three weeks ago, the Competition Commission published both some initial, and then more detailed, findings into the purchase of City Screen Limited by Cineworld Group plc, thus putting Cineworld and Picturehouse cinemas under the same ownership. This has been deemed by the commission to have created a substantial lessening of competition (SLC), and the only solution on the table at the moment is to force Cineworld to sell off one of its cinemas in Aberdeen, Bury St. Edmunds and Cambridge. There’s been much talk in the last two weeks about protecting what the Picturehouses provide in terms of quality, differentiation, accessibility and ancillary services – not least from me, as I helped to start a petition which has gained 10,000 signatures in a week and a half – but all that seems to be pointing to the logical solution being to sell off the Cineworld in each area. Right? WRONG.

Nearly three weeks ago, the Competition Commission published both some initial, and then more detailed, findings into the purchase of City Screen Limited by Cineworld Group plc, thus putting Cineworld and Picturehouse cinemas under the same ownership. This has been deemed by the commission to have created a substantial lessening of competition (SLC), and the only solution on the table at the moment is to force Cineworld to sell off one of its cinemas in Aberdeen, Bury St. Edmunds and Cambridge. There’s been much talk in the last two weeks about protecting what the Picturehouses provide in terms of quality, differentiation, accessibility and ancillary services – not least from me, as I helped to start a petition which has gained 10,000 signatures in a week and a half – but all that seems to be pointing to the logical solution being to sell off the Cineworld in each area. Right? WRONG.

I can say for certain that this blog wouldn’t exist without cinemas that offered the quality and diversity of the Picturehouses, but it almost certainly wouldn’t have existed without the Cineworlds either. Over the years, I’ve blogged on some crazy feats of cinematic endurance, such as seeing seven films in a day or 100 in a year, but stunts like that wouldn’t be possible without the benefits of a Cineworld card. But I’m far from the only person who sees films regularly in a cinema, and if you’re a Cineworld member the benefits are plenteous. The current price of a Cineworld membership is £15.90 a month and in the vast majority of Cineworld cinemas, that’s less than the price of two full adult tickets. You can then see as many films as you like, and that opens up a whole world of possibilities. And if you think I’m the only person taking advantage of consuming films in large quantities, then take a look at Cineworld’s twitter feed to see the kind of company I keep. The first year I saw 100 films in a year? Cost me just over £300 for the tickets.

If this is starting to sound like an advert for Cineworld, then this next paragraph is only going to make matters worse. Any members get 10% off concessions, which instantly starts to make the overpriced popcorn that little bit less overpriced. There are also Unlimited members screenings, where at least once a month anyone with an Unlimited card can get a ticket to see a big name film before it’s on general release. I’ve been to a few this year, and the likes of Trance and 2 Guns have been packed out. (And because it’s an Unlimited showing, there’s no charge, of course.) If you’ve been a member for 12 months or more, then it’s an automatic upgrade to Unlimited Premium, which means there’s nothing extra to pay for 3D films – normally a surcharge of around £1.50, in line with most other cinemas – and you now get 25% off any of the concessions, at which point a bag of sweets will cost you around the same as it would in a high end supermarket, rather than an average cinema.

But of course, the Commission haven’t taken memberships into account when judging the risks or benefits to consumers. Which is why they believe the cinema chain doing the most in the country to encourage loyalty in its members and to give them significant reductions in return is likely to increase its prices by 50p or less in an effort to drive customers up the road to the Picturehouse, in turn increasing the overall profits to the company. Yes, seriously. (Picturehouse being the only other chain of more than 10 cinemas in this country to have a membership scheme which gives direct discounts on actual tickets. ODEON have a points club, but you even have to use your points to pay their online booking fee. Anyone who’s publicly stated they would rather have an ODEON than a Cineworld, and I’ve seen a few, should think on that for a moment.)

Now, you might think that I only know that the grass is green on my side of the fence. But travelling for work as much as I do, I also visit cinemas of the other chains when I’m in the unfortunate position of working somewhere without a Cineworld or Picturehouse in reasonable distance and still want to catch a film. So in the past three years I’ve visited the following cinemas that aren’t a Cineworld.

Vue: Cambridge, Leeds, Edinburgh, Cheshire Oaks, West End, Romford

Odeon: Covent Garden, West End, Panton St, Newcastle

Showcase: Coventry, Peterborough

Empire: Leicester Square

Curzon: Soho

Others: BFI Southbank / IMAX, ICA, Prince Charles, The Aubin, The Barbican, Sheffield Screen Room, The Luxe (Wisbech)

[Picturehouse: Cambridge, Bury St. Edmunds, Hackney, Stratford, Liverpool]

I’d like to think I have a fair basis for judging the on site quality of other cinemas, and there is nothing in terms of the experience of visiting any of these cinemas that leads me to believe any benefits of one of them taking over one or both of my local Cineworlds would outweigh the cost. What all of these cinemas have in common for me is that I’ve only seen one film in them per visit, and rarely – if ever – visited more than one of them in a given month. That’s the reality of what could be facing residents of Cambridge and Bury St. Edmunds if we lose one or both. (Aberdeen has two Cineworlds, so the path of what to do there seems a little clearer, as being required to sell one cinema would leave them with at least one Cineworld.)

So what does this mean for the quality argument? Surely there aren’t enough good films around to justify seeing more than two a month anyway? As evidence to the contrary for that point, I now present a sample list from the last five years of high profile films, most of which I would rate highly, that I wouldn’t have seen in a cinema without the Cineworlds of Cambridge or Bury St. Edmunds had I been forced to restrict myself to just the two films that month I most wanted to see.

Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead, Charlie Bartlett, Adulthood, Choke, Doubt, Paranormal Activity, Where The Wild Things Are, I Love You Phillip Morris, How To Train Your Dragon, Heartbreaker, Cyrus, Back To The Future re-release, Rango, The Inbetweeners Movie, The Awakening, The Hunger Games, Magic Mike, Pitch Perfect, The Impossible, Cloud Atlas, Olympus Has Fallen, 2 Guns, About Time

But that’s not all that the Cineworlds offer. Outside of four cinemas in the West End, you can use your membership card at any cinema. So that three year list of cinemas from earlier? Here’s my comparable Cineworld list to the other chains from earlier.

Cineworld: Cambridge, Bury St. Edmunds, Huntingdon, Haverhill, Enfield, West India Quay, The O2 Greenwich, Runcorn, St. Helens, Stevenage, Wood Green

And if you add those nine other Cineworlds not affected, then the list of films I wouldn’t have seen without my Cineworld card expands once more:

Black Dynamite, Barney’s Version, Snowtown, Moneyball, Coriolanus, Young Adult, The Grey, The Descendants, A Dangerous Method, The Hunter, Anna Karenina, The Perks Of Being A Wallflower, Zero Dark Thirty, Spring Breakers, Byzantium, Behind The Candelabra, The East

And that’s just the good stuff. I get to sit through all kinds of nonsense, from Transformers: Dark Of The Moon to Gnomeo And Juliet, safe in the knowledge that I’m paying a flat monthly fee and I’m effectively seeing these films for free, typically at a rate of around 10 films a month. Does this sound like the kind of cinema operation to you about to engage in a large scale attempt to discourage customers away from its cinemas?

If you don’t want to lose Cineworlds in Cambridge or Bury St. Edmunds either, you only have until 17:00 on Tuesday 10th September (tomorrow at the time of writing) to make your feelings known. Contact them at CineworldCityScreen@cc.gsi.gov.uk to make sure they understand there’s no easy solutions to this issue, only a whole host more problems if they carry on their current course, and it’s consumers – not Cineworld themselves – who are the most likely to lose out in all this.

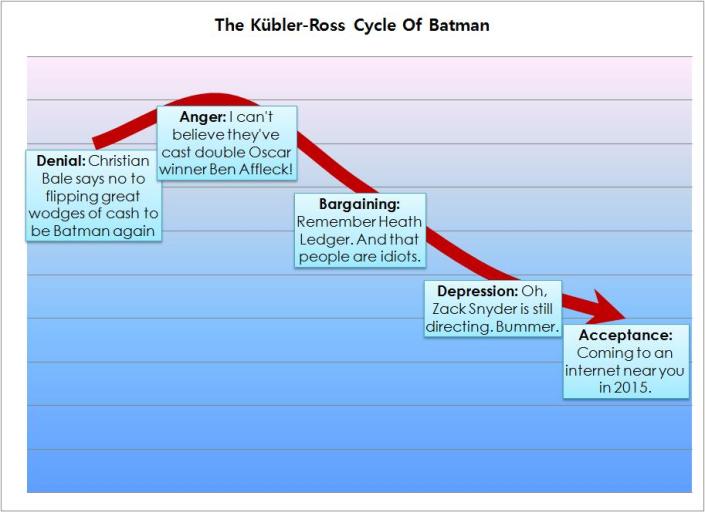

The Kübler-Ross Cycle Of Batman

Ben Affleck will be appearing in numerous supercuts of people saying “I’m Batman” in around 2 years. In case you hadn’t heard.

Ben Affleck will be appearing in numerous supercuts of people saying “I’m Batman” in around 2 years. In case you hadn’t heard.