Cambridge Film Festival

Cambridge Film Festival Review: Midnight In Paris

The Pitch: We’ll always have Paris. Which Paris is the question…

The Pitch: We’ll always have Paris. Which Paris is the question…

The Review: You might remember the days when Woody Allen made universally acclaimed films. Sadly, in the eyes of most, the last time that happened consistently was probably the Eighties, and since 1989’s Crimes And Misdemeanours it’s been a succession of moderate successes and critical flops. But nostalgia is a powerful feeling, and every time a new film appears with Woody’s name on, you can feel everyone lining up, ready to give it a kicking but most actually hoping that somehow the easy charm and clever dialogue of his earlier hits could still be recaptured. If only he could travel back in time to understand what made his earlier films so successful…

Maybe it’s that constant nostalgic reflection, or maybe it’s the inspiration of the latest city to be his muse after his mixed London years, but the inspiration for Midnight In Paris of that nostalgic element seems to have revitalised Woody, and this is probably his best film since the Eighties. It’s easy to claim that there’s a formula to a good Woody Allen film, but actually what makes this one so refreshing is his willingness to stick to the formula, albeit with a few subtle variations. A lot of his best work deals with the metaphysical and is rooted in high concept, from Zelig to The Purple Rose Of Cairo and Deconstructing Harry, to name just a few, and Midnight In Paris gets its gimmick from a completely different side to Paris that Owen Wilson’s Gil discovers after midnight.

What Woody’s never had a problem doing is assembling a great cast, and this is no exception. One of those subtle variations on the theme is the Woody avatar that the central character normally represents (if it’s not Woody himself of course), and Owen Wilson is at his extremely likeable best as the bemused and frustrated writer, but it’s a role that Wilson does bring different aspects to, not least a wide-eyed astonishment at the events unfolding. The likes of Michael Sheen and Rachel McAdams offer solid support, but the other stand out is Marion Cotillard as Wilson’s muse, who seems to attract men like flies and has most of them around her little finger. There’s also plenty of background roles with actors having huge amounts of fun, and Alison Pill and Adrien Brody especially light up the screen in their brief turns.

The irony, of course, is that a film that’s so obsessed with nostalgia manages to successfully recapture the magic of Woody Allen’s days gone by. Midnight In Paris is a light soufflé of a film and would probably blow away in a strong wind, but it’s a delight from start to finish and Allen gets the most out his slender concept. Key to the film’s success are Allen’s early Parisian navel-gazing, which means that once the plot kicks in, the pace fairly rattles along, that the cast make the most of their varied roles and that it’s all wrapped up satisfactorily at the end of the reasonable running time. For any Woody fans, they’ll be thrilled that their hero has managed to find himself once again; for the more general film fan, it’s a great concept executed in a thoroughly entertaining way, and let’s just hope it doesn’t take Mr Allen another twenty years to hit these heights again.

Why see it at the cinema: Paris hasn’t looked this good since Ratatouille, and Woody’s bringing the chuckles back so it’ll be a good night out with the middle classes.

The Score: 9/10

Cambridge Film Festival Review: The Debt

The Pitch: Some debts take longer to pay off than others.

The Pitch: Some debts take longer to pay off than others.

The Review: Sam Worthington could very well be the Kevin Costner of his generation. Kevin had a knack for the dramatic equivalent of being the straight man in a comedy show, a stoic pivot at the centre of a film where those around him would do all the heavy lifting in the acting department. From JFK to The Untouchables, from Field Of Dreams to Robin Hood, Costner assembled a diverse body of work, most of which is excellent and most of which he’s doing less acting than his colleagues in. Worthington has already secured a number of lead roles, and has now been inexplicably cast in an ensemble drama where he’s required to act at the same level as both his contemporaries and some great actors of earlier generations.

I would love to say that Sam steps up and knocks it out of the park, but consider the acting talent he’s been recruited with. At the older end, you’ve got Helen Mirren, Tom Wilkinson and Ciaran Hinds portraying the Nineties versions of the lead trio, retired Mossad agents who achieved glory in their younger days. In the contemporary category, Martin Csokas and Jessica Chastain, with Chastain especially marked out for great things after her last lead role opposite Brad Pitt in The Tree Of Life. Against that kind of competition, Worthington never stood a chance, but if the film had used him to his best effect, rather than putting him through the harrowing experience of asking him to act (you can almost see the acting gears churning behind his concentrated face), then it need never have been a problem.

You see, there’s two competing films in here, and The Debt is never quite sure which one it wants to be. There’s the exploits of Worthington’s trio in Sixties Berlin, attempting to track down a Nazi war criminal (the excellent Jesper Christensen) and to bring him to justice, and the human drama of their conflict both in the Sixties and in the Nineties. Scenes between Chastain and Christensen are excellent, and the drama is exploited for all of its meaty possibilities; the thriller elements, involving the capture and fate of the team’s quarry, are also tense and keep the attention throughout. It’s just the use of personnel at certain points that allows the film to flag a little, which isn’t the fault of the actors but could have been remedied either by writers Matthew Vaughn, Jane Goldman and Peter Straughn or by director John Madden with a little more care.

The other failing of the film also has to be placed with writers and director. While I’ve never attempted to act myself, I did once study the piano, and my teacher told me that if I looked after the start and end of the piece, the middle would take care if itself. If only Madden and co had been able to heed this advice; the start is flabby, and consists of over twenty minutes of flashbacks and forwards and sideways glances and the characters not stating their true purpose, all of which mean that The Debt takes much longer than it should to gain momentum. The ending is also problematic, not least when a film that recasts its core roles between generations suddenly has one actor turn up in very poor old age make-up, and also when the final twists and turns descend into silliness and stifle the dramatic resolution. The Debt has brilliant parts, but is less satisfying as a whole and someone needs to work out quickly how to use Sam Worthington – for both his sake and ours.

Why see it at the cinema: If you can get past the choppiness of the opening then there’s a large chunk of a good film here, and seeing it in a cinema will fully allow the tension to grab you and draw you in. On the way out, you can see how many people kept a straight face all the way to the end…

The Score: 7/10

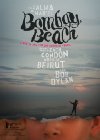

Cambridge Film Festival Review: Bombay Beach

The Pitch: The Beach Boys: The Lost Generations.

The Pitch: The Beach Boys: The Lost Generations.

The Review: There are plenty of stereotypes that come to mind when one thinks of America; from the brash New Yorker to the ultra-hip Californian, American ways of life vary more often than time zones as you move from east to west. Attempting to define an American way of life isn’t easy, but Bombay Beach is a unique documentary which attempts to give insight into the lives of average Americans who have one thing in common – they are living in a run-down, almost forgotten backwater (pop. 260) where the American dream seems to be closer to a nightmare.

The 1% of the Beach’s inhabitants that we do follow each have their own problems. The youngest, Benny, comes from a family who’ve had more than the odd run-in with the law and Benny’s mother is doing her best to balance the medications prescribed to moderate his youthful recklessness. CeeJay is a school student hoping to be the first in his family to make it to college, after being sent away from the violence surrounding his Los Angeles home. The eldest of the three, Red, is eking out his final years in the crumbling surroundings with the support of others but still has the odd indulgence to make his later life enjoyable.

The stories of these three and their friends and families reflect a lot of what we think we know about America – as well as the mundanity of middle America being taken to extremes, the stories give insight into the everything from the prescription drug culture to the gun culture which blights the US, but attempts to put it into the context of the regular lives of these small-town folk. Director Alma Har’el spent a year chronicling the lives of the residents of this failed resort and is never afraid to get up close and personal with her subjects, getting the camera right into people’s faces and eavesdropping on fights and tantrums in an attempt to understand what makes them tick. Despite the shabby surroundings, all three subjects seem keen to make the best of their lot in life and their story is one as much of hope as it is of destitution.

Emphasising that hope, Har’el has each of her subjects take part in a choreographed dance routine. Using the music of Zach Condon and Bob Dylan and the various dance routines, Bombay Beach is transformed from measured to magical, as if Har’el has managed to capture the very essence or soul of her subjects. Har’el doesn’t attempt to draw too many conclusions, instead allowing the viewer to make up their own mind, and that allows the more extravagent touches to be at their most effective. The setting might be bleak, but somehow it serves to inspire both its residents and the filmmaker and Bombay Beach is a moving, thought-provoking and uplifting snapshot of life on the poverty line in the American heartland.

Why see it in the cinema: Not only for the fantastic use of the desolate landscapes, but also the intimate character work which makes great use of the wide screen, and plenty of humour to share in the mix as well.

The Score: 8/10

Cambridge Film Festival Review: The Purple Fiend

The Pitch: Action! Adventure! Ninjas! Disaster! Intrigue! And a mysterious purple extremity…

The Pitch: Action! Adventure! Ninjas! Disaster! Intrigue! And a mysterious purple extremity…

The Review: I like to consider myself half the man that Francois Truffaut is – I’ve started being critical of other people’s work, but not yet decided to go the whole hog and attempt to prove that I can do better. In which case, I must also be half the man of a number of local Cambridge film-makers, who have been inspired by the efforts of others to make their own micro-budget films under the banner of Project Trident, and now have completed their magnum opus, the very long short film The Purple Fiend.

For a labour of love and such a personal project, the scope of The Purple Fiend is nothing short of epic. It follows the adventures of Professor Laminut and his faithful companion Googy, refined and well spoken gentlemen who are know to undertake the occasional odyssey or trek, on their quest to find the Sacred Colocolo of Porabolus, a mission with divine implications and which must be completed before the end of the year. So why is Laminut still in the bar on New Year’s Eve at twenty minutes to midnight…?

There’s always a risk with such projects that the joke might be lost on outsiders, but such pitfalls are skilfully navigated. Carl Peck directs his cast well, and the performances are all committed and energetic; the thirty minute running feels packed to the gills with incident and invention, and there are some special effects of both the practical and visual nature that go to show what can be done with a lot of commitment and a bit of patience. Simon Panrucker’s orchestral score is also worth mention as it also helps to give the finished product a professional sheen. While much of the action takes place in the bar of the Arts Picturehouse, the venue for the film festival of which Project Trident is part (and liable to lead to a blurring of fantasy and reality for hardened festival goers), the confined space doesn’t cramp the wit or invention and some judicious location shooting helps to balance this out.

Let’s not forget that this is the work of enthusiastic part-timers; amateurs is very much the wrong word as the anarchic energy on display in the fight scenes and the refusal to give in to normal constraints such as logic are commendable. Taken on its own terms The Purple Fiend is a great half hour of anyone’s time and stands as testament to the efforts of those involved with Project Trident over the past few years. It’s not going to win any Oscars – but then again, neither did Truffaut and that never stopped him, did it?

Why see it at the cinema: I saw it with this year’s other Project Trident efforts, and as this was last up it was around a quarter to one in the morning by the time the projector fired up, following an intermission and a second trip to the (about to be famous) bar for many of the audience. In terms of timing, content and setting, I can think of few better partnerships: ideal served late on a Friday night with a few beers, a lot of friends and plenty of laughs.

The Purple Fiend was also made with the cinema, rather than the small, screen in mind, and the sweeping vistas and copious gore feel right at home on the big screen.

The Score: 8/10

Cambridge Film Festival Review: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy

The Pitch: Dobby, King George VI, Dumbledore’s brother, Jim Gordon. The Elephant Man and Sherlock can barely get a look in…

The Pitch: Dobby, King George VI, Dumbledore’s brother, Jim Gordon. The Elephant Man and Sherlock can barely get a look in…

The Review: Ten years ago, Gary Oldman was a different man. One of the best actors of his generation, but famed for disappearing into his roles and for not making easy choices, he had a certain familiarity to popcorn audiences for the likes of Leon and The Fifth Element, but may not have been a household name. Big roles in the Harry Potter and Batman franchises have sorted that out, but he’s always been able to retain the varied qualities that helped him to stand out in his less familiar roles. But it’s those qualities that undoubtedly caused the producers at Working Title to conclude a six month search by landing on his name, and also realising that they couldn’t make the film without him. The most successful remakes are able to make you forget that there was ever a previous incarnation, and Alec Guinness’ boots are some big ones to hide.

The Seventies Smiley story was rightly lauded for the strong cast and the faithfulness of its adaptation, so once the challenge of finding a lead has been overcome the next is to find a way of condensing the material that fed a six hour TV series into a reasonable length. The first surprise is that Tomas Alfredson and his editor have somehow condensed this into two hours; the second is the leisurely pace at which the film seems to start, almost as if it’s not concerned with getting through the material in the prescribed running time. But it’s actually more measured than leisurely, the tone able to shift seamlessly and deliver drama and tension from even the most underplayed scenes.

Having one of the best casts in, frankly, ever also manages to keep your attention through every twist and turn of the plot. There’s a lot of names on the poster, but everyone steps up and delivers top-notch performances. Worthy of particular mention are those outside the Circus’ top tier, and Tom Hardy and Benedict Cumberbatch continue what should be upward trends in their career paths. Mark Strong, Toby Jones, John Hurt and Colin Firth also don’t disappoint, and the likes of Stephen Graham and Kathy Burke also shine enough in smaller roles that they should probably be disappointed not to get their names on the poster. Oldman, of course, glides through the middle of it all, giving a masterfully subtle performance that deserves attention when awards start to be handed out.

The actors having set the bar, pretty much every other department steps up to meet it. From the costume and production design to the photography and editing, quality oozes out of every frame, and Alfredson succeeds in glueing your eyes to the screen for every second, and manages to throw in as many indelible images as he did in his stellar vampire effort, Let The Right One In. There’s a surprising sprinkling of humour and a definite helping of passion thrown into the mix, which help to leaven the more serious and studious moments. The music is also well worth a mention, regular Almodovar composer Alberto Iglesias turning in a score which evokes just the right mood and has enough echoes of previous spy scores without feeling too referential or reverential, and the use of music itself not only drives key plot points but also adds dramatic weight to key scenes, especially near the climax.

Ultimately, your overall enjoyment of Tinker… will depend on how much you feel you’re actually following the plot. There are two potentially deciding factors in this: one is the use of flashback to expand on the inital set-up, and while the subtitles are happy to draw the distinction between Russian and Hungarian, for example, the point in the time line of the film isn’t always as obvious. However, the fate of two key characters is laid out early on, and using them as a compass point should allow you to easily work out where the plot’s up to. The other is the use of the characters’ emotions to imply their motivations – sideways glances and background detail are often preferred to dialogue, and this feels more natural but does demand your full and undivided attention for the entire running time. If you’re paying close attention to those emotional beats, the final reveal shouldn’t come as a surprise, even if you haven’t read the book or seen previous adaptations. If you can keep these two things in mind, then this is an outstanding piece of cinema which should leave you needing a second viewing almost immediately.

Why see it at the cinema: The production design and cinematography are as outstanding as everything else, and the close up view and attention to detail demand you see this in a cinema. Also, the post-screening mumbling as you exit will allow you to determine how many people actually followed it.

The Score: 10/10

The Half Dozen Special: Cambridge Film Festival 2011

It barely seems possible that a whole year has gone by since last year, but I guess that’s how calendars work, so no point trying to fight it. September is here again, so it’s time for the 31st Cambridge Film Festival, and for me the second experience of one of the UK’s foremost festivals of film. Having lived in Cambridgeshire for three years, I’d never even seen a single film at the festival, but last year made up for it in spades, in the end seeing nineteen films over the eleven days of the festival. You can see the full list here on last year’s Half Dozen, but there were some real gems in there. I may not have seen the likes of The Desert Of Forbidden Art, Pelican Blood, Dark Souls or The People vs George Lucas if there weren’t playing at a festival, and I didn’t see a single film that I regretted. In addition, the surprise film, which everyone I spoke to had pegged as everything from The Social Network to Despicable Me, turned out to be Chico & Rita, which was a delight. I can only hope to be similarly surprised again this year.

It barely seems possible that a whole year has gone by since last year, but I guess that’s how calendars work, so no point trying to fight it. September is here again, so it’s time for the 31st Cambridge Film Festival, and for me the second experience of one of the UK’s foremost festivals of film. Having lived in Cambridgeshire for three years, I’d never even seen a single film at the festival, but last year made up for it in spades, in the end seeing nineteen films over the eleven days of the festival. You can see the full list here on last year’s Half Dozen, but there were some real gems in there. I may not have seen the likes of The Desert Of Forbidden Art, Pelican Blood, Dark Souls or The People vs George Lucas if there weren’t playing at a festival, and I didn’t see a single film that I regretted. In addition, the surprise film, which everyone I spoke to had pegged as everything from The Social Network to Despicable Me, turned out to be Chico & Rita, which was a delight. I can only hope to be similarly surprised again this year.

Ah yes, this year. My cinematic obsession still knows no bounds, it seems, so this year’s trailer run down is somewhat longer. So far I’m booked to see 34 films, as well as talks by Mark Kermode and Neil Brand and the festival’s late night short film festival, Tridentfest. I’m going in having seen one of the 34 already – Drive, which is so good I couldn’t pass up the chance to see it again at the Festival, especially when director Nicolas Winding Refn is due to be there, but even though it’s my second favourite film of the year so far, I live in hope that something will sneak up, surprise me and manage to beat it. And in the process of writing this I’ve already had two recommendations of films that happen to be playing at the Festival that I’m not seeing – yet! Read the rest of this entry »

Review Of The Year 2010: My 10 Best Cinematic Experiences

Regular readers of this blog will know that, two years ago, I set myself the task of watching 100 films in a year, simply to see if it could be done without going mad or incurring serious injury. Well, it turned out that it could, I did, seeing 107, and now non-regular readers know this too, as I’ve not stopped going on about it ever since.

Well this year, I had different aspirations. I just wanted to see as many good films as possible, plus a few indulgently bad ones and whatever my wife wanted to see. Starting to blog, though, has led me down lots of dark and dangerous paths, most of which have lovely warm cinemas at the end, so that’s all right, then. It sounds like the worst kind of modern reality TV cliché, but I have discovered this year that cinema really is as much about the experience as anything else, and sometimes you have to invest a little in that experience yourself to get the most out of it. So here is my unashamedly personal run-down of my ten best experiences in a cinema this year.

10. Discovering that there might be the odd person or two who is interested in what I think about movies

Well I haven’t been completely without readers, although the majority of people who’ve been to my blog have done so because I have the sixth most popular image of Peter Pan on Google. (Image search “peter pan” if you don’t believe me.) But to all who’ve braved this blog this year and possibly found something worth their time, I thank you. Fortunately I do write this for my own benefit to a certain extent, so readers aren’t essential, but they are nice, all the same.

9. Seeing some hard to find films in far flung locations

I’ve put the miles in this year. My nearest cinemas are all twenty miles away, in different directions, but I’ve also clocked up a few trips to London (coming up later) and some insane mileage to see some other movies I liked the look of, including 110 mile round trips to see a Date Night / Cemetery Junction double bill and also City Island, 126 miles to see MacGruber / Please Give and a titanic 134 mile round trip to catch Black Dynamite, having already seen another film somewhere else that day.

8. Seeing my favourite film of all time on the big screen

8. Seeing my favourite film of all time on the big screen

I was eleven when Back To The Future first burst onto cinema screens, and it was a time when the cinemas near where I lived were dying out, so VHS had become our only movie-viewing option at the time. I loved it, then, have fallen for it increasingly over the years, and a trip to see it on the big screen in October confirmed its place in my heart as my favourite of all time. I then wrote about 88 reasons why it was so great, which helped to put my blog into a review backlog from which it has never really recovered. Great Scott!

7. Seeing my first old classic in a packed house

I’ve also been more than a bit sniffy in the past about seeing older movies in the cinema, but came to the realisation that these should be cherished and appreciated as much, if not more so in many cases *cough* Michael Bay’s output *cough*. So while in London, meeting a friend I’d made on Twitter for the first time (another unique experience for 2010), we took in the showing of The Shop Around The Corner at the BFI, which played to a packed house, and got more laughs than anything else I saw all year.

6. Becoming completely uninhibited when showing my emotions in movies

6. Becoming completely uninhibited when showing my emotions in movies

For many years, my family have attempted to maintain that I blubbed my eyes out when watching E.T. at the cinema when younger, and I will still hear none of it. Other than a slight eye-related moistening when watching Babe in 1995, I had remained the dry eye in the house all the way up to last year, to Up in fact, when those Pixar bastards caused me to blub repeatedly like a little ginger baby (see left). It seems that the floodgates of my emotions have now been opened; Toy Story 3, Mary and Max, Winter’s Bone, Of Gods And Men, none of which made me cry, but at all of which I coincidentally seemed to have something in my eye. Sniff.

5. Getting to talk to Mark Cousins in an extended Q & A

I managed to catch Mark Cousins’ The First Movie when it was on tour in October, at the Cambridge Arts Picturehouse. The lovely people there got him to stay for a twenty minute Q & A afterwards, and then a second Q & A was organised, in a little meeting room upstairs at the back of the screens. About two dozen of us huddled in on a circle of chairs, like some kind of Cinemaholics Anonymous meeting, and grilled him for another forty-five minutes on his brilliant film, cinema in general and anything else we could think of. I never would have thought of opportunities such as this previously, but would consciously seek them out now, and would encourage you to do the same.

4. Going to an IMAX double bill

4. Going to an IMAX double bill

If you’ve never been to an IMAX showing, then you haven’t lived. Sadly there are only a dozen in this country, and half of those are sort of mini-IMAXes, which sort of defeats the object. But for a sound and vision experience unlike any other, then you need to get to one if you ever get the chance. I saw an opportunity earlier this year for a unique double bill, and saw Inception (for the second time) and Toy Story 3 (for the first) on the biggest screen in the country. It was an amazing experience, and the best sound (for the former) and picture (of the latter) of any films I saw this year.

3. Hosting my very first Q & A with a director

Not content with sitting in on Q & A sessions and attempting to hog all the questions, I also ended up actually hosting one, with director Richard Bracewell, who also wrote the Richard E. Grant / Tamsin Greig / Laura Fraser thriller Cuckoo that might just still be in a cinema near you. The chance to meet up and absorb that knowledge and enthusiasm was a real thrill, Richard was a delight and I was simply glad to be able to introduce him to an audience of fellow film lovers. This may not be the last you hear of me; I look forward to what 2011 has in store in that regard.

2. Attending my first film festival

I’ve lived in the Cambridgeshire area for three years now, and in that time had not, even once, ventured into the film festival, being a little unsure what to make of it all. Late last year I was flicking through the brochure and came to realise quite how many cinematic treats and early releases I’d missed out on, so resolved not to make the same mistake again.

So this year, I booked the week off work, warmed up the debit card and booked myself in for eighteen different screenings over the course of eleven days. An unfortunate ticket printing mix-up on the first evening meant that I then had seventeen of those tickets in a little pouch, which I carried round like a giant ginger Gollum for the next week and a half, but not going to see at least a film a day became a real culture shock at the end of the period. In the end I added in one more, for a final total of nineteen, and there wasn’t one in that I regretted seeing.

I also managed to get to three more Q & A sessions, talking to a fantastically diverse range of people, but my closest encounter came on the last day. Parking problems meant that I arrived at the cinema late for the start of my first screening, a fab Norwegian horror called Dark Souls, and as I opened the first of the two doors into the cinema a man greeted me and filled me in on the very brief amount of plot I’d missed. “Oh, and by the way, I’m the director,” he said. “Nice to meet you,” I replied. You wouldn’t get that at a normal screening.

1. Attending my first movie convention

But the undoubted highlight of my year was attending the BFI / Empire Movie-Con in London in August. Three days of fabulous previews, more Q & As (including where I got to ask Edgar Wright the price of a pint of milk, to a round of applause from my fellow Movie-conners, and then, bowled over as I was by his utterly amazing movie and caught up in the moment, attempted to tell him the philosophical, love conquers all answer, to a chorus of general boos. Oh well, can’t win ’em all) and constant drama. I blogged extensively at the time about the trials and tribulations of getting a ticket, then getting there at all, but it was worth every second of the drama and the agony.

It was the purest distillation imaginable of what makes cinema great; a fantastic venue (the BFI’s NFT1, where even my back row seat had an acceptable view), great sound and vision, Kim Newman’s Bastard Hard Film Quiz, where I got the Pixar tie-breaker all correct, but nowhere near enough other answers for that to be of any use, and even sat just behind a couple who got engaged on stage. I also made a great collection of new friends, all of whom were bonded through the adversity of just being there in the first place.

I’m already looking forward to Movie-Con IV, although I do plan to get my ticket in person this year to attempt to avoid that drama; I hope all of the drama will be on the screen and not in my life next year. Here’s to whatever the experience of cinema has to offer me next year.

Cambridge Film Festival Review: The People vs. George Lucas

The Review: I was born at just the wrong time. I’ve already written before how it took a while for the cultural impact of Star Wars to take over my life. I had the toys when I was younger, but I had my first lightsaber fight at university after The Phantom Menace came out, and I bought the gorgeous artwork and making of books of Revenge of the Sith, so I knew the story before I even saw the movie. There’s a part of me that would like to think these were as good as the originals, but deep down I know the truth and I was probably overcompensating for a misbegotten childhood (in all the wrong ways). But there’s no denying that Star Wars changed the direction of movies and popular culture permanently and irrevocably when it landed; that said, the legacy today is more ire of what has come in the last 15 years than fond remembrance of what was there before.

The People vs. George Lucas is an attempt to understand that paradigm shift in the cultural impact of George Lucas’ most prominent creation (although there is also some reference to his second most, Indiana Jones). Few movies before or since Star Wars have fundamentally changed the perceptions and ideals of those watching, but in doing so some sense of intellectual property seemed to pass into the audience. So when George started to make improvements to the originals, and then took a new trilogy in the directions he wanted, then that audience wasn’t happy. If anything, they wanted blood, or revenge (at least until they got Revenge), but they’d probably have been happy for it just to stop…

Director Alexandre O. Philippe uses a very loose and slightly neglected courtroom framework to construct his narrative, but this is a largely linear wander through the most famous missteps of George Lucas post-Howard The Duck, using a combination of talking heads and fan-made films submitted via the web. Particular attention is given to the special edition re-releases and the subsequent sequestering of the original versions, and indeed to the most controversial alterations to them (don’t mention Greedo – I mentioned him once, but I think I got away with it), and the sheer level of ill feeling summoned up by the prequels, the fourth Indiana Jones movie and the continuing evolution of George as a hate figure for those who once adored him.

What feels like polemic about a third of the way through and almost a call to arms for oppressed Jedi across the galaxy by half way actually takes a much more balanced view by the end. Of course, no one who wasn’t in love with the originals could have conceived this, and while the view may be balanced, there’s no attempt made to justify Lucas’ actions over the period, or indeed to suggest right or wrong. What it does work as, very effectively, is a primer for those looking to understand how not to keep a legacy going, and indeed to start a debate whether any event will have the same impact again, or whether its creators would even want that legacy and the pressure that comes with it.

I know what you really want to know, though – what’s my view? Because everyone must have one who’s lived through this. Although I don’t love any of the last / first three Star Wars movies as much as the originals, Phantom Menace has the best music track (Duel of the Fates) and the best lightsaber fight of all six and the first twenty minutes of Revenge of the Sith were what I used to illustrate to my wife, who’s never seen Star Wars (sigh) what a Star Wars movie should be like. I was more crushingly disappointed by the fourth Indiana Jones movie than any of the prequels, and Spielberg must be as much to blame for that. In fact, when did he last make a truly great movie? Ten years ago? Fifteen? Has George ever descended into mawkish sentiment and unbelievability with quite as much regularity as Steven? Next case, The People vs Steven Spielberg, if you please.

Why see it at the cinema: Everything and anything about Star Wars should be seen in a cinema, and since this is better than the prequels themselves, and you saw those there, you should be seeing this there. Simple.

The Score: 8/10

Cambridge Film Festival Surprise Film Review: Chico & Rita

The Pitch: Hello, and welcome to Jazz Club. Tonight, a jazz love story. Mmm, nice.

The Pitch: Hello, and welcome to Jazz Club. Tonight, a jazz love story. Mmm, nice.

The Review: When I was growing up, I had a very fixed perception of animation; understandable, since my niece is currently going through the same diet of wall-to-wall Disney films, there’s just a lot more of them about these days. Thankfully, TV came along with The Simpsons and South Park and showed that animation can take many forms and can have many purposes, but it’s still a rarer occurrence than would be preferable to see something different gain an audience in the field of animated movies. (In the ten years of the animated movie Oscar, for example, there hasn’t been a single truly adult animation nominated, although Waltz With Bashir rightly got into Best Foreign Language.) But Chico & Rita is that rare beast that can deliver a grown-up animation, and feel fresh into the bargain.

The setting for the movie is twofold; a framing device of an old man listening to the music of his youth, which turns out to be literally his music. He’s Chico, a talented young pianist in Havana in the late Forties with an ear for jazz. His eye for the ladies falls on Rita, a singer whose voice enchants him as much as her appearance. They begin to make music together, but so begins a tempestuous love story that takes them from Havana to America, taking in the jazz scene at a pivotal moment in its history, but also reflecting critical developments in the evolution of their homeland.

The movie has a distinctive visual style, using rotoscoping to capture the actors from live action, with the supplementation of computer animation. This gives the movie a more idealised and romanticised feel which perfectly complements the storytelling, but also allows the performances to come through and gives a sense of realism in the emotions. (There’s also something about brief full frontal nudity from animated characters that oddly made me more prudish than live action would have done, but I’m pretty sure that’s just me.)

The story navigates seamlessly between the cities and the timeframes, but the star, other than the scenery and the process, is the music itself. Jazz has a history and a passion that’s made it probably the most influential musical development of the twentieth century (sorry, rock’n’roll, nothing personal, just the way I feel), and this is a love letter to the music wrapped up in a love story that spans decades. If your only knowledge of Tito Fuente is from that famous Simpsons episode, then you need to treat yourself to this pair and their compelling story, for if you do, a genuine and unexpected pleasure awaits you.

Why see it at the cinema: The visuals are lush and overtly cinematic as the journey takes you across countries. But being in a cinema with a good sound system will also give you the chance to fully envelop yourself in the gorgeous soundtrack.

The Score: 8/10

Cambridge Film Festival Review: Made In Dagenham

The Review: The true (or inspired by) story of the plucky underdogs who rise up and achieve has become a staple of British cinema over the past two decades. In everything from Brassed Off to Calendar Girls, that feeling of gritty realism that is still gritty in a faintly British, middle class way, more Richard Curtis than Mike Leigh or Ken Loach, so a movie such as Made In Dagenham comes loaded with expectations. It is almost inevitable that a story such as this, ripe for such a big screen conversion, would be made eventually, but thankfully this version comes loaded with talent and packed with quality.

It’s a simple concept: female workers at the Ford Dagenham plant, who make up a tiny proportion of the overall workforce as they supply the stitched seating and other accoutrements, feel that their low pay and lower grading in comparison to their male colleagues (most of whom are husbands who work in the main plant) are unacceptable, and spurred on by sympathetic shop steward Albert (Bob Hoskins) they begin the battle to get their rights, led by the reserved but determined Rita (Sally Hawkins). Soon their actions get the attention of the government and the female Secretary of State, Barbara Castle (Miranda Richardson), but the question is how far will they be willing to go, or indeed will their husbands want them to go?

The script does a nice job of offsetting the familial tensions created between the two sides of the workforce with the ongoing struggles to get their case heard. Hawkins, Hoskins and Richardson are all playing the type of roles they’ve played before, but in each case bring something fresh; Hoskins has an understated cheekiness and fits well into the all female environment, Hawkins has the fearless optimism from previous roles such as Happy-Go-Lucky’s Poppy, but also handles herself well in the more heated exchanges at home with husband Eddie (Daniel Mays), and Richardson perfectly captures the bold-as-brass, no nonsense attitude of the Secretary and her unwillingness to back down, even when up against the Prime Minister (John Sessions’ slightly caricaturish Harold Wilson). The supporting cast are all excellent, especially Geraldine James as Hawkins’ right hand woman and Rosamund Pike as her unlikely ally from the middle classes.

We may think we know where the story’s headed, but there’s pain and pathos in the transition, and director Nigel Cole keeps things moving along well, never allowing the pace to sag but still finding time for the dramatic moments to breathe when the time is right. The grimness of the working conditions and the brown Sixties tones are a wonderful setting for such a story, and the whole package has just the kind of feelgood nature, but tinged with something deeper, that the best of its contemporaries has tried to capture. Hopefully British audiences haven’t tired of this kind of story yet, as Made In Dagenham proves that there’s still plenty of interesting avenues to explore in the story of the plucky Brit.

Why see it at the cinema: The Sixties design, shown off at its best on the London escapades, shines through the struggles and will capture you visually, but this is a feel good entertainment – you’ll feel better in the company of lots of others.

The Score: 8/10