review

Review: Life Of Pi 3D

The Pitch: Crouching Dragon, Hidden Tiger.

The Pitch: Crouching Dragon, Hidden Tiger.

The Review: Sometimes in life you have to put aside trivial matters and get to grips with the weightier questions of the universe. Why are we here? Where did we come from? Is there a God, or possibly Gods? And will 3D ever become a successful film making tool or forever remain a cheap gimmick? Well, the latter may not be weighing heavily on your mind, but trust me, it’s given me a few sleepless nights. You can count the number of truly successful directors in the medium on the fingers of one hand: Martin Scorcese, James Cameron, Michael Bay (and that in itself is a depressing notion), but now you can add Ang Lee to that list. Impressively, that’s not the only question on the list he’s attempted to tackle in this gorgeous and reasonably faithful adaptation of Yann Martel’s novel.

Many familiar with the novel thought it unfilmable and it had a strange structure for certain, divided broadly into two halves. Pi (played at middle age by Irfan Khan) sits down to tell a story to a writer looking for a story to tell (Rafe Spall), which starts at his childhood in India and details his adolescence and the key role his parents come to play in his development. It’s that development that then upsets the balance of Pi’s life, as the family zoo is being relocated to Canada for financial reasons, so the family and their menagerie is loaded to a cargo ship. The second half deals with the aftermath of a wild storm which sinks the ship and leaves Pi (played here by Suraj Sharma) afloat with a handful of animals, most notably an untamed tiger with the unlikely name of Richard Parker, and Pi is left to fight for his survival in more ways than one.

It’s the combination of unlikely characters, setting and material that would seem to make this a difficult film to adapt. First then to the film’s look: it’s simply stunning. The vivid colours and bold framing capture your attention from the first moment and never look like relinquishing it, but it’s the use of 3D that truly stands out. Not only does Lee understand the technical demands that a third dimension places, with constant use of fades and slow pans to keep everything in focus, but he also has fun with the toolkit, even throwing in aspect ratio shifts here and there to maximise the potential of the format, and rather than the normal 2D-plus-occasionally-poking-things-in-your-face, this truly feels like a film thought of, framed in and shot for three dimensions. More than that, Lee even uses that third dimension both to increase tension and as a narrative tool on occasion; if there’s been a more effective 3D movie in the modern era, I’ve yet to see it. The techniques used to bring the animals to life are for the most part flawless, with CG and real animals virtually indistinguishable. The soundtrack by Michael Dynna is also worth a mention, serving as an excellent backdrop for the varied emotional states the film seeks to evoke.

But no point in looking gorgeous if there’s nothing going on between your ears, and here Life Of Pi also doesn’t disappoint. It’s not to say that it’s the most sophisticated story ever told, coming over as park bench philosophising at times (a visual metaphor that the film plays out in an attempt to inject movement into its more talkative aspects). That occasional heavy-handedness is felt throughout, particularly in the last fifteen minutes – which comes perilously close to grating – but this is very much of the mythological, exploring the nature of storytelling itself through the fable that Pi takes us through but also prompting us to ask questions about what belief means and examining the possibilities of existence. It’s a tricky balancing act to maintain between story and visual and Lee manages it through never letting the story itself get too bogged down, especially tricky when you have so few characters – and even less of them with speaking parts – for such a large chunk of the running time. As well as that slight heavy storytelling hand, Life isn’t quite as profound as it thinks it is, or would like to be, its storytelling dissection being just that and falling short of the treatise on religion it initially claims. That’s balanced by a refreshing lack of sentimentality as Richard Parker’s sea-based buffet unfolds in the second half, which extends throughout most of the story.

In terms of those characters, Life Of Pi represents another step forward, as the seamless blend of green screen, CGI and other more practical techniques have reached a point where a recreation of a living creature can interact seamlessly and never be anything less than utterly convincing. That also has to stack up against a living actor, and Suraj Sharma gives a powerful portrayal of the more youthful Pi, easily matching the ferocity of his feline foe but also getting to the root of Pi’s own inner turmoil. I’m prepared to forgive pretty much every one of those flaws mentioned earlier, for what Ang Lee has crafted is very much a modern cinematic treat, a feast for the eyes that is at the cutting edge of its medium with just enough nourishment for the mind as well. It may not change your thoughts on God or the nature of existence, but it might just capture a few 3D skeptics and fans of old fashioned storytelling.

Why see it at the cinema: Whether you watch in two or three dimensions, Life Of Pi is a work of art, both visually and aurally and as with so many art works, should be seen on a suitably sized canvas.

Why see it in 3D: But if you’re still undecided on whether 3D can bring anything to the cinema experience, you should be trying this with the glasses on.

The Score: 10/10

Review: The Master

The Pitch: “The Church of Scientology has not yet published a comprehensive official biography of [Lafayette Ron] Hubbard.” – From the Wikipedia entry for L. Ron Hubbard.

The Pitch: “The Church of Scientology has not yet published a comprehensive official biography of [Lafayette Ron] Hubbard.” – From the Wikipedia entry for L. Ron Hubbard.

The Review: “After establishing a career as a writer, becoming best known for his science fiction and fantasy stories, he developed a self-help system called Dianetics which was first published in May 1950.”

If you look up the definition of a cult, it refers to the repetition of religious practice and the sense of care owed to the gods or shrine. In terms of those elements of the definition, the works of Paul Thomas Anderson could well be seen to fit that description, with a new work from PTA not only required viewing for his followers, but also following increasing trends and patterns. The course of his career has seen a number of unconventional character studies, ranging from the sprawling ensemble of Magnolia to the tightly wound intensity of There Will Be Blood, but always one pair of characters stands out from the others in terms of that study, to the point where TWBB was practically a two hander. So it will come as little surprise that The Master again is a study in character, and takes that trend further forward to the point where the character study is the plot, or at least what could best be regarded as one.

“The Church of Scientology describes Hubbard in hagiographic terms, and he portrayed himself as a pioneering explorer, world traveler (sic), and nuclear physicist with expertise in a wide range of disciplines, including photography, art, poetry, and philosophy.”

So The Master is what’s become known as Anderson’s Scientology film, but anyone expecting a rigorous analysis or critique of the most infamous cult religion of the 20th century should turn back now. The Master is layered with such detail or comments from the life of Scientology’s founding father, L. Ron Hubbard, but instead built largely into the life of Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman). What Anderson is looking to understand is the persuasive power of leadership, and Dodd’s ability or otherwise to exert that power on his followers; in the case of the film, one Freddie Quell (Joaquim Phoenix). Where TWBB saw the relationship dynamic between Paul Dano’s immovable object and Daniel Day Lewis’s irresistible force, here Dodd and Quell are both more dynamic, occasionally two forces directed explosively together but as often two objects thrown apart.

“He served briefly in the United States Marine Corps Reserve and was an officer in the United States Navy during World War II, briefly commanding two ships, the USS YP-422 and USS PC-815. He was removed both times when his superiors found him incapable of command.”

Dodd doesn’t actually appear on screen in the first half hour, the film preoccupied with Quell’s initial journey into the company of The Cause (the film’s on-screen name for its own cult). Anderson is keen to explore the how as well as the why, but the what forms components of story rather than a structured framework. What has divided audiences is that lack of structure, so it’s left to the performances to draw you in. Phoenix especially is mesmerising, never likeable or especially sympathetic but showing enough volatility to keep him interesting. Hoffman’s performance might be more understated, but carries credibility in terms of his ability to both motivate and occasionally infuriate. (It’s also worth noting that both Dodd and Quell seem to have been influenced by Hubbard’s real life back story, further playing up the duality of their relationship.) Although there’s a wide supporting cast, few others outside these two make any kind of impact.

“He has been quoted as telling a science fiction convention in 1948: ‘Writing for a penny a word is ridiculous. If a man really wants to make a million dollars, the best way would be to start his own religion.'”

If you wanted to guarantee success in film, you’d probably be out making a series of films about teenage vampires battling alien wizards from the future, as the more unlikely it is, the more commercial it will be. But quality can also bring success, and The Master has quality running through every one of its production values, especially in Mihai Malaimare Jr.’s sumptuous cinematography and Jonny Greenwood’s dangerous, provocative music. The overall effect creates a mood that will totally consume many viewers but may further alienate those looking for something definitive to latch on to. But for those willing to give themselves totally over to Anderson’s vision, there’s much to dissect and plenty to take, even if Anderson does give himself over to an occasional indulgence (and yes, I’m looking at you, naked party scene).

“At the start of March 1966, Hubbard created the Guardian’s Office (GO), a new agency within the Church of Scientology that was headed by his wife Mary Sue.”

Appearances can be deceptive, and just as there’s more going on with most cults than you’d see on the surface, there’s more to The Master than the central relationship. Key to the new dynamic here is Lancaster’s wife Peggy (Amy Adams), who flits around on the periphery but seemingly has influence over Lancaster at key moments. Phoenix’s performance may be the most showy but Adams to elevate The Master that level further, performing that classic trick of women’s roles of doing a lot when not much is given (or, at least, initially appears to be). It’s these character moments that will likely dictate your level of appreciation for The Master; if the tangential exploration of cults in general and Scientology specifically, welded to the stunning character work and wrapped in some of the finest cinematic trappings available, is enough then you, like me, could probably watch this on a loop. If, however, the lack of narrative momentum and sympathetic characters are likely to bother you, then The Master is unlikely to recruit you to the cult of Anderson.

“He was a member of the all-male literary banqueting club the Trap Door Spiders, which served as the basis of Isaac Asimov’s fictional group of mystery solvers the Black Widowers.”

Sequel, anyone?

Why see it at the cinema: It’s impressively filmed and performed, looks and sounds incredible even in the digital version (although I do hope to revisit it in 70mm early next year), and is absolutely one of those films you need an opinion on if you have a love of film for that debate in the bar afterwards.

The Score: 10/10

Review: Amour

The Review: Michael Haneke is one of those directors from whom the label auteur clearly applies; he’s probably one of that select band that could become an adjective, and any film given that description will give the viewer a clear idea of what to expect; moral ambiguity, a desire to get the viewer to experience a strong reaction, a dissection of the art of cinema itself, with a tendency to staccato bursts of violence and often an alienating coldness. Haneke’s 2009 film, The White Ribbon, picked up the Palme D’Or at Cannes and gained more affection that most of his previous films, based in no small part on the sympathetic central characters and even more surprising bursts of tenderness. For his latest film (picking up his second award on La Croisette), Haneke again takes things to extremes, although this time it’s that most human experience that he’s keen to push to its limit.

His real master stroke here is in the casting. Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva have both had long, colorful and reasonably distinguished careers but now carry the heft of their actual years (Trintignant takes his first part in about a decade at 81; Riva, while still working regularly, is now 85). Not only do they convincingly portray two lives being lived to their fullest and latest extremes, but they have a believable chemistry that makes their portrayal of a couple being driven apart by the onset of their years all the more poignant. There’s also quality in the supporting cast, not least from Isabelle Huppert as the frustrated daughter seemingly unable do anything but stand at the sidelines and watch on helplessly.

What plays out is the story of the end of this couple’s relationship, at a time when their love for each other seems to be stronger than ever, almost painfully so. Although we’re left in no doubt as to the eventual outcome by the first scene, the initial scenes of general life and affection from Trintignant and Riva make it all the more harrowing when Riva first suffers her stroke, and from then on the depiction of life’s difficulties is about as honest as you could imagine. From there, the performances diverge with Riva required more to show the ravages on the body of old age, while Trintignant must bear the burden of her afflictions mentally and spiritually. Both performances are of the highest order and between them, Anne and Georges (a regular Haneke touch) will put you through the emotional wringer.

So to the director himself, and Michael Haneke’s using a few other regular tricks here, including a wide shot in a theatre early on with the characters almost lost in the background (but for their age, they’d be completely invisible). As always, every single detail is meticulously planned and fine tuned, with even the title coming over as very deliberate (Amour, lacking the usual French definitive article of the more romantic sounding L’Amour). Generally, he keeps the direction slow and deliberate, restricting the surprises to a dream sequence and a visit from a pigeon later on. But in terms of Haneke’s achievement, Amour successfully encapsulates the devastation of the passage of time and the inevitability of old age, and it feels almost churlish to say that’s all it does, lacking slightly some of the complex insights or more deliberate provocation of Haneke’s other works. There’s certainly a purity and simplicity in terms of the insight to the human condition in comparison to the other best works of Haneke, but odd details (such as the dream sequence) jar due to the deep-seated reality of what surrounds them, and when the ending comes it doesn’t quite feel like the true gut-punch it should, drenched in the inevitability of both its own film maker and the narrative course it’s taken. Still another significant achievement in the career of Michael Haneke, and confirmation that a heart does beat within his chest after all, even if it has a darkness to it.

Why see it at the cinema: Haneke’s works are designed to be seen in the cinema, from the first shot after the credits to the intensity of the ending, so that’s where you need to be to commit yourself fully.

The Score: 9/10

Review: Sightseers

The Pitch: Oh, living in a house, a small wheeled house in the country! Got relationship deceit and some murd’rous feats in the country! Count-ra-a-aaay! (with apologies to Blur)

The Pitch: Oh, living in a house, a small wheeled house in the country! Got relationship deceit and some murd’rous feats in the country! Count-ra-a-aaay! (with apologies to Blur)

The Review: I’ve never quite understood the appeal of caravans. Even in the UK, there are so many fine hotels, B & Bs and hostels that the idea of packing up a few treasured possessions in a small house on wheels and setting off for a muddy field with a communal bathroom. But if you absolutely want to make your own itinerary, then they’re probably idea, but it still takes a certain kind of person to want to go caravanning; possibly a little nerdy, certainly very British, and maybe with a tendency to murder people at the slightest provocation. (Wait, what?) Yes, there is apparently a fine line between genial and insane, and the new film from director Ben Wheatley takes a journey to the heart of a very British darkness.

The story stems from an original idea by Alice Lowe and Steve Oram, who started playing the two characters on stage, thought of a move to TV, but then executive producer Edgar Wright and director Wheatley got involved and the adventures of Tina and Chris (Lowe and Oram playing the characters as well as scripting alongside Wheatley’s co-writer from Kill List, Amy Jump) as they trek round some of the British countryside’s more esoteric delights, from the Crich Tramway Museum to the Keswick Pencil Museum. Along the way, they meet a variety of the countryside’s typical residents, but it quickly becomes clear that neither Tina nor Chris is equipped with a full set of social skills, and what start as minor irritations soon turn into something much more threatening.

It might be better described as a bleak comedy rather than a black one, given the isolated settings, but Sightseers certainly doesn’t skimp on the comedy itself. It’s clear that Lowe and Oram have a lot of love for the characters they’ve created, and their actions and reactions to the world around them feel both perfectly grounded and just the right side of creepy. Of the two, it’s Lowe who probably has the slight edge, Tina being afforded a slightly better selection of the choicest lines and also getting the more thoughtful character arc. She also has the advantage of an overbearing, housebound mother (Eileen Davies) to feed off for further character development, and it’s with Tina that your sympathies are most likely to be engaged.

The other star of the film is the British countryside, with carefully chosen venues that Sightseers avoids poking fun at, although there are some great gags squeezed out of a couple (most notably the pencil museum). The film tries not to play its hand too early, with Wheatley employing a leisurely pace – arguably a little too leisurely – in the opening scenes before the nature of the pair’s trip forces them to pick up the tempo. Just occasionally, Wheatley’s reach exceeds his grasp and the budget restrictions expose themselves, but not in any of the murderous episodes, where the claret is liberally spilled and the weaker stomachs in the audience may find themselves turning over slightly. For a film with such big backdrops, it does occasionally still feel very small scale, but there’s much to like in the tale of Tina and Chris; I don’t know if it’s going to make any caravan converts though, you just never know who might be staying in the next pitch…

Why see it at the cinema: Ben Wheatley does make absolutely the most of the country locations – a little too much on occasion – but as long as you can find an audience with the same sensibility, there should be plenty of communal laughs. (Possibly not the audience I saw it with, where the other six people on the front row all walked out before the end. Their loss.)

The Score: 8/10

Review: Silver Linings Playbook

The Pitch: Madness is all in the mind.

The Pitch: Madness is all in the mind.

The Review: If you visit my Twitter profile, you’ll find this at the top of the page, my vaguely self-deprecating description:

Now, for anyone that’s read any amount of this blog, you’ll be aware that I have a somewhat addictive personality. When I invest in a subject, I tend to invest hard, having seen 635 films in the cinema in the last five years and 447 of those since I started writing this blog. But if you think that’s an actual OCD, then you’re very wrong; obsessive, clearly, but it lacks the physical compulsions which can debilitate its sufferers and in the most severe cases ruin their lives. I’ve always known that the day I start a family is the day that my cinema dwelling will dwindle to nothing for a while, and I’m ready for when that day comes. But from schizophrenia to psychosis, mental illness is generally misunderstood in our society, so any film looking to imbue its characters with such afflictions would be advised to tread carefully.

Silver Linings Playbook features a number of characters who have an array of mental difficulties: Pat (Bradley Cooper) is discharged from a mental hospital after his mother (Jacki Weaver) intervenes, but struggles to come to terms with both his home life and the absence of his wife, estranged after Pat’s bipolar disorder came to the fore when he catches her cheating. His only real friend (Chris Tucker) is still struggling with his own mental health issues and regularly attempts to escape from the same hospital, but even he can see that the more classically depressed Tiffany (Jennifer Lawrence) has an interest in Pat, but both Pat and Tiffany have their own deeper motivations for wanting to spend time with the other. Meanwhile Pat also struggles to reform a bond with his father (Robert De Niro), who shows his own signs of both obsessive behaviour and addiction and which start to come to the fore when Pat struggles.

In terms of the film itself, it’s worthwhile trying to separate the characters from their afflictions for the depictions of mental illness are shaky at best. Oddly, Chris Tucker fares best in that respect, as he appears outwardly normal and little attempt is made to characterise his illness, which actually makes his the best description. For the others (Pat / Pat Sr. / Tiffany) the seeds of their illnesses can be seen, but the characteristics are poorly sown by David O. Russell’s script (based on Matthew Quick’s novel) and somehow the Asperger’s syndrome of Pat’s literary counterpart attempts to become bipolar disorder here. It wouldn’t matter so much if the characters were more generally well written, but the script gives them little else to feed off for most of the time and when it does, the contrast is sharp; Jennifer Lawrence fares best in that respect, again getting the chance to show off the skills that got her recognised for Winter’s Bone and in one pivotal scene, waltzing in and acting everyone else, De Niro included, off the screen. Cooper, De Niro, Weaver and even Tucker put in good work but this turns out to be Jennifer Lawrence’s show.

Successfully portraying mental illness on screen is one challenge that Silver Linings meets only with partial success; the other half hearted attempt is to put a new wrinkle on the romantic comedy. For a film so serious for much of its running time, the occasional laughs sit uncomfortably, although thankfully they are driven out of the situations and never at the expense of the characters themselves. But the third act turns into the kind of romantic comedy plot that’s hamstrung the careers of the likes of Katherine Heigl and Gerard Butler, and it’s only the likeability of Lawrence and Cooper that helps to see it through. It is predictable in the extreme, and once the pieces are laid out the last act plays out with a total lack of surprise and not much more suspense. It’s a totally mixed bag directorially from Russell as well, shepherding his characters through to the resolution with only occasional flashes of the touch which he’s shown in his best films. A mixed bag all round then, worth seeing for the performances but not doing very much to advance just about anything else.

Why see it at the cinema: The drama of the last act comes across well in the cinema, even if it is lacking in surprise, but it’s not enough of a comedy to benefit from the audience buzz and there’s nothing remarkable in direction or cinematography. If you’re keen, worth catching in the cinema, but otherwise wait for the DVD.

The Score: 6/10

Review: The Sapphires

The Pitch: Less purple hearts, more purple dresses.

The Pitch: Less purple hearts, more purple dresses.

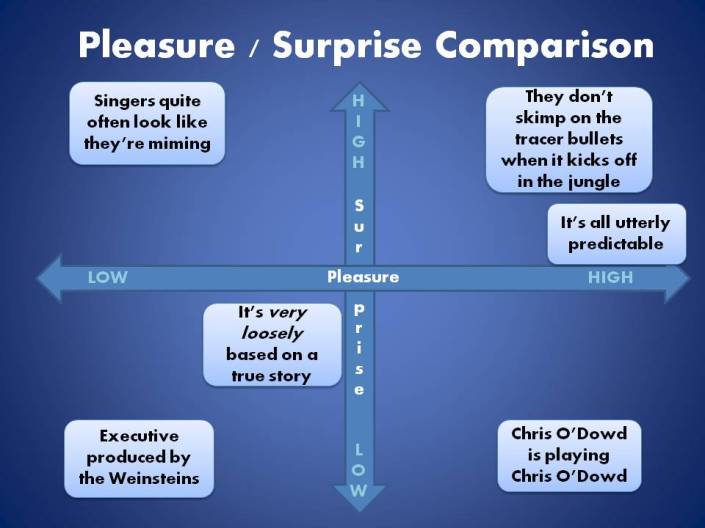

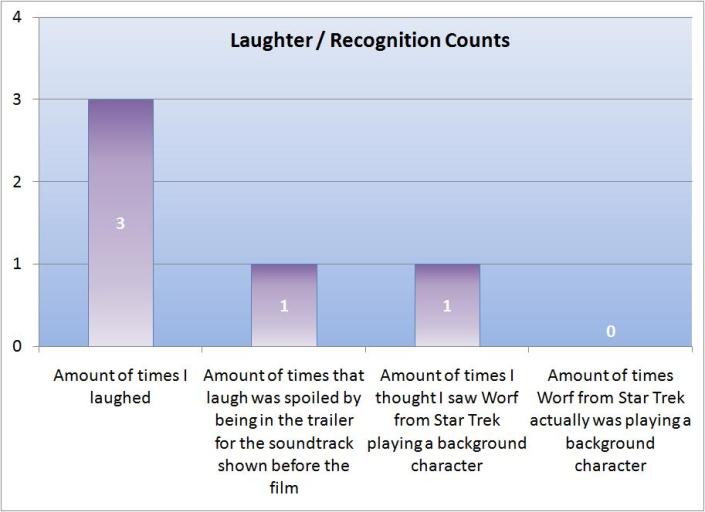

The Review In Graphical Format:

Why see it at the cinema: It does achieve the feel good ambition, so it you’re looking for a midweek lift, you could do worse.

The Score: 6/10

Review: Rust And Bone (De rouille et d’os)

The Pitch: Love is… never having to say you’re sorry (for the killer whales and street fighting, apparently).

The Pitch: Love is… never having to say you’re sorry (for the killer whales and street fighting, apparently).

The Review: If you’ve never seen a Jacques Audiard film before, then you should come to this with the right expectations: that what you’re going to get will be a little unconventional, to say the least. Take his last three films: Read My Lips, involving the pairing off of an almost deaf woman with an ex-convict, or The Beat My Heart Skipped, the story of a shady real estate broker with aspirations to be a pianist. Audiard’s last film, A Prophet, was less concerned with romantic aspirations but still took a hard-boiled prison drama and wove supernatural elements inextricably within it. So if you’re coming to Rust and Bone completely cold, you should be aware that Audiard’s films are anything but simple.

It will be no surprise in that context that Rust And Bone sees a return to romance, but also that it’s not your average boy meets girl. In this case the boy is a big hulk of a man, Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts) who’s trying to find the means to raise the young son he’s been saddled with looking after, but it’s difficult when responsibility doesn’t come easy to him. Through one of his many attempts at respectable work as a nightclub bouncer, he has a chance encounter with Stephanie (Marion Cotillard), whose hotheadedness gets her in trouble at the club before Ali intervenes. A begrudging act of kindness on her part later becomes more crucial when she suffers an unfortunate and potentially devastating accident; through that, this odd couple start to become friends, but form a complex relationship which both of them struggle to truly come to terms with.

Audiard is no stranger to powerful male figures in his films (the last three have featured Vincent Cassel, Romain Duris and Tahar Rahim, for example), and Matthias Schoenaerts seems to have been hewn almost from solid granite, such is his imposing physical presence. But the real strength comes from the performance of Marion Cotillard, now no stranger to English speaking audiences for her work with the likes of Michael Mann and Christopher Nolan. Most reviews are giving away the nature of what happens to her character, and given that she’s a killer whale trainer it’s maybe not hard to surmise, but I’ll leave that for you to find out on screen if by some miracle you don’t already know; either way, the pain of self-discovery is powerfully captured by Cotillard, but that’s only the start of an excellent performance that sees her take a surprising, but always believable, journey through that pain and towards some form of a normal life.

It’s fair to say that Audiard’s film isn’t necessarily concerned primarily with the difficulties of dealing with disability. There’s an awful lot more going on here, from Ali’s street fighting career to his stewardship of his son to the nature of his relationship with Stephanie to the issues of socialism and family brought up by some of the divisions between management and employees where Ali also works. With so much happening, not every plot line gets the time it needs (Ali’s son suffering most from this) and also not every plot feels that it’s earned its time in the mix. Whenever Cotillard’s on screen, Rust And Bone captures and keeps your attention, but when she’s not, it has to work a little harder, and while it’s not a constantly captivating film when it’s at its best, it soars. But it’s fascinating to see what can be done with modern special effects, no longer purely the domain simply of big Hollywood productions, and for the most part Audiard has produced another compelling story of human relationships with a twist to stand shoulder to shoulder with his earlier works.

Why see it at the cinema: Audiard knows how to use the frame, and there’s at least a couple of moments that pack a much bigger punch for being seen in a cinema for their emotional wallop.

The Score: 8/10

London Film Festival Review: Robot And Frank

The Review: Consciousness is a fragile thing. Somehow, the collection of atoms and molecules that make up our brains manage to form thoughts and memories, and thankfully the organ that stores that operations centre in each of us has a fairly hard shell protecting it from shocks and damage. Sadly, the one thing it can’t protect us from is the passage of time, and sooner or later that will catch up with all of us. It’s amazing that something so complex keeps running for so long in most of us, and despite the advances in science in the 21st century the finest minds of all of us haven’t yet managed to either successfully extend that lifespan, or indeed to replicate the complex functions that make us human. But when science gets to that point, will we be accepting of our new robot friends, or fear our potential new overlords and the uprising that might follow?

It’s common for films to assume the latter, despite the fact that the appliance of science generally seems to be directed to make life more comfortable for us mere mortals. Robot & Frank follows the former path, and when his son Hunter (James Marsden) decides he needs to devote more time to his own family, rather than weekly ten hour round trips to his ungrateful father Frank (Frank Langella), he gets him a robot (voiced by Peter Sarsgaard). Initially both he and his world traveller absentee daughter (Liv Tyler) are resistant to the idea, but once Frank latches onto the potential of a robot friend, his enthusiasm grows. Frank, it seems, has a shady past and sticky fingers, one he’s not even keen to share with the lady at the library who’s caught his eye (Susan Sarandon), and what better sidekick than a piece of easily swayed modern technology with Frank’s best interests at heart?

At its core Robot and Frank is a poignant tale about memory and the passage of time. While set in the future, the shading and details make it feel close to our own time, but just as believable as other, grander, futuristic vistas in bigger budget films. It’s not about the technology, but the lack of that personal connection, and those like Frank still clinging to the physical elements of the world are seen to be relics, almost museum pieces. Frank’s failing memory occasionally sees him drifting into the world of his past, and there’s a deep poignancy to his yearning for the restaurant now replaced by a home store or the library throwing out all of its books.

But deeper than that is the exploration of family. Frank’s son and daughter come across initially as disaffected and tied only by the obligation of bloodlines, but it becomes clear that for every action, there’s a reaction and Frank’s certainly seen a lot of action. That Robot & Frank succeeds so well in that family dynamic is down not only to the strength of the performances from those involved, but also to the script and direction, which invests the characters with genuine emotion and which manages to pull off some late twists deftly, without the feeling of soap opera melodrama.

At the core of the movie in every sense are the two titular characters. Initially reluctant to take on his robot servant, Frank starts to see the possibilities and runs through the whole range of potential clichés, from odd couple domestic drama to mismatched buddy heist movie and eventually to surprisingly tender and almost heartbreaking scenes as Frank starts to form the kind of bond with a machine he’s never managed with a human. Warm and resonant, but playful and mischievous and ultimately deep and thought-provoking, Robot & Frank packs a wide array of ideas into its slender running time, and handles every single one beautifully. If you ever imagined having your own robot as a child, the thought of that coming true might just equate to the joy that Robot & Frank could bring; the prospect that it never will in our lifetimes may just match the bitter-sweet feeling you’ll get from it as well.

Why see it at the cinema: See this with a big audience to share the emotional rollercoaster, as well as a decent selection of laughs from the inappropriate OAP.

The Score: 10/10