Cambridge Film Festival

Cambridge Film Festival Diary: Day 6

Day 6, the halfway point in the festival, and also the halfway point in my viewing plans for the festival. Seeing so many films now starts to take on something of the feeling of being halfway down a long, dark tunnel; my skin is starting to suffer slightly from the lack of sunlight – some moisturiser soon sorts that out, at least on a temporary basis – but more than that, the effects of sitting down in the same position for six to ten hours a day are starting to affect both my body and my mind.

The solution to that problem is a little more obvious – stop spending six to ten hours a day in the cinema – but it’s a solution I won’t have the luxury of for nearly another week. So by this point I started to dispense with the normal facing forward sitting position, adopting an increasing number of variations, including a sort of side-saddle and a splayed crucifix where only a small amount of me was in contact with the seat. I had to try to keep the variations down as the week went on, lest people think me a horrendous fidget, but it did just about save me from pins and needles, or worse, as the week wore on.

This, however, was what was on screen in front of my fidgeting on Tuesday 18th September.

Jiro Dreams Of Sushi For the second time in two years, I saw a documentary about a three star Michelin restaurant at the film festival. Jiro was a noticeable improvement over last year’s El Bulli, not least because it spends as much time understanding the proprietor as it does the restaurant. Sushi looks deceptively simple, just some rice, some raw fish, a little wasabi and some seasoning, but David Gelb’s documentary successfully illuminates quite why chefs need to spend up to ten years learning some of the more refined techniques before they can truly call themselves proficient, and why a man of eighty-five is still working day in, day out to create some of the finest cuisine in the world. It also takes a look at what the future might hold for both this restaurant, and a second run by one of Jiro’s sons (not the only one to enter the family business), given the longevity and dedication of their respective head chefs. I had sushi for lunch straight after the film, but I know it wasn’t a patch on Jiro’s. The Score: 8/10

Jiro Dreams Of Sushi For the second time in two years, I saw a documentary about a three star Michelin restaurant at the film festival. Jiro was a noticeable improvement over last year’s El Bulli, not least because it spends as much time understanding the proprietor as it does the restaurant. Sushi looks deceptively simple, just some rice, some raw fish, a little wasabi and some seasoning, but David Gelb’s documentary successfully illuminates quite why chefs need to spend up to ten years learning some of the more refined techniques before they can truly call themselves proficient, and why a man of eighty-five is still working day in, day out to create some of the finest cuisine in the world. It also takes a look at what the future might hold for both this restaurant, and a second run by one of Jiro’s sons (not the only one to enter the family business), given the longevity and dedication of their respective head chefs. I had sushi for lunch straight after the film, but I know it wasn’t a patch on Jiro’s. The Score: 8/10

Notorious The second of my Hitchcock films of the week, and while still in black and white, this now benefits from the addition of sound. It also benefits from the addition of some of the finest stars to ever grace the silver screen, including Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman and Claude Rains. It has a fairly tortuous MacGuffin, but Notorious just goes to show why the details of those were never important, when the central love triangle is so strong. One of Hitchcock’s most successfully romantic films, it’s also a stunning example of just how good a director he was, getting supreme performances from his actors but also working his camera incredibly well, and the whole party sequence is an absolute joy and a thrill from start to finish. Grant and Bergman make a satisfying screen couple (due in no small part to Grant’s off screen coaching, apparently) and seeing it on the big screen confirmed its place in my top 5 Hitchcocks. The Score: 10/10

Notorious The second of my Hitchcock films of the week, and while still in black and white, this now benefits from the addition of sound. It also benefits from the addition of some of the finest stars to ever grace the silver screen, including Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman and Claude Rains. It has a fairly tortuous MacGuffin, but Notorious just goes to show why the details of those were never important, when the central love triangle is so strong. One of Hitchcock’s most successfully romantic films, it’s also a stunning example of just how good a director he was, getting supreme performances from his actors but also working his camera incredibly well, and the whole party sequence is an absolute joy and a thrill from start to finish. Grant and Bergman make a satisfying screen couple (due in no small part to Grant’s off screen coaching, apparently) and seeing it on the big screen confirmed its place in my top 5 Hitchcocks. The Score: 10/10

The Idiot Another carry-over theme from Monday, this time the Estonian cinema thread, but unlike the previous day’s Temptation Of St. Tony I found The Idiot a somewhat frustrating experience. Based on the Dostoevsky novel of the same name, The Idiot is the story of a Russian prince who returns to his homeland after years away in an asylum in Switzerland. Once back, he manages to fall for not one but two women, and slowly but surely his innocence in such matters and the personalities of the two women start to make all of their lives unravel. The first act is strong, not only setting out the narrative clearly but with excellent staging and some nice touches, including a contemporary twang to the soundtrack. Sadly, as the film progresses the staginess takes over, the invention becomes more and more absent and the whole production becomes dry and airless.

The Idiot Another carry-over theme from Monday, this time the Estonian cinema thread, but unlike the previous day’s Temptation Of St. Tony I found The Idiot a somewhat frustrating experience. Based on the Dostoevsky novel of the same name, The Idiot is the story of a Russian prince who returns to his homeland after years away in an asylum in Switzerland. Once back, he manages to fall for not one but two women, and slowly but surely his innocence in such matters and the personalities of the two women start to make all of their lives unravel. The first act is strong, not only setting out the narrative clearly but with excellent staging and some nice touches, including a contemporary twang to the soundtrack. Sadly, as the film progresses the staginess takes over, the invention becomes more and more absent and the whole production becomes dry and airless.

By the last act, the courage of any convictions has been lost and certain scenes – for example, when one character sends another a hedgehog as a metaphor for their relationship – lack any sort of sense that they belong in the same film. (It would be worth mentioning that it was at this point I became slightly hysterical, which may be the reaction every time I see a hedgehog from now on.) If only the mood and inventiveness of the first third could have been maintained, The Idiot would have been excellent, but sadly it goes down as at best a brave attempt. The Score: 4/10

Anda Union All of the other films in the festival I saw were showing at the spiritual home of the festival, the Cambridge Arts Picturehouse, but I had determined I would make one trip out to one of the other venues to take in a film. That turned out to be the last in a series of films showing at the Cambridge Buddhist Centre, in this case a documentary about Mongolian music group Anda Union. I wasn’t 100% convinced about the venue; while the projection and sound that had been set up were excellent, my first attempt at a seat (in what could be best described as the stalls, in what was originally a Victorian theatre) left me craning my neck too much to see the screen, my second seat was behind a curtain with no view of the screen at all and my third had a flip chart board blocking half the screen. Thankfully the screening was only sparsely populated, otherwise I may have been struggling for a decent seat.

Anda Union All of the other films in the festival I saw were showing at the spiritual home of the festival, the Cambridge Arts Picturehouse, but I had determined I would make one trip out to one of the other venues to take in a film. That turned out to be the last in a series of films showing at the Cambridge Buddhist Centre, in this case a documentary about Mongolian music group Anda Union. I wasn’t 100% convinced about the venue; while the projection and sound that had been set up were excellent, my first attempt at a seat (in what could be best described as the stalls, in what was originally a Victorian theatre) left me craning my neck too much to see the screen, my second seat was behind a curtain with no view of the screen at all and my third had a flip chart board blocking half the screen. Thankfully the screening was only sparsely populated, otherwise I may have been struggling for a decent seat.

In terms of the film itself, the documentary tracks the group on a 10,000 kilometre journey across the steppes and plains as they meet with family and friends and take their music wherever they go. Showing everything from the production of their instruments through to concert footage, it’s a fascinating insight into a life in another world, and while there are no earth-shattering revelations from the footage following them travelling, the music itself is thrilling. It’s a mixture of string instruments and percussion, coupled with both throat singing and more conventional singing, and with track names like Ten Thousand Galloping Horses, the passion for their people and their culture shines through. The Score: 7/10

Sinister Last up was my third visit to the Late Night Frights thread, for a haunted house chiller starring Ethan Hawke. The premise is stripped back to the bare bones, and all the more effective for it; Hawke plays a novelist who’s based his career on true crime investigation, but his last hit is disappearing into the distance at an ever increasing rate, and he’s going to increasing lengths to get a few more minutes of fame to add to the fifteen he’s already had. Alienating the police before he’s barely set foot in the town, he finds a box of Super 8 footage and a camera in the otherwise empty loft space, which hold the key to the horrors of more than he realises.

Sinister Last up was my third visit to the Late Night Frights thread, for a haunted house chiller starring Ethan Hawke. The premise is stripped back to the bare bones, and all the more effective for it; Hawke plays a novelist who’s based his career on true crime investigation, but his last hit is disappearing into the distance at an ever increasing rate, and he’s going to increasing lengths to get a few more minutes of fame to add to the fifteen he’s already had. Alienating the police before he’s barely set foot in the town, he finds a box of Super 8 footage and a camera in the otherwise empty loft space, which hold the key to the horrors of more than he realises.

Sinister absolutely nails the atmosphere, and has the feel of a high end, high quality Stephen King adaptation about it. The last time I jumped out of my seat in the cinema was during Neil Marshall’s The Descent, so credit to Scott Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill for causing my seat and I to part company. The one real flaw is with Hawke’s character, who has two unfortunate afflictions required to maintain the tension; he repeatedly makes poor decisions in terms of his own and his family’s safety, happy to hide behind an unspoken truth not being a lie, but that’s compounded by the fact that every single person in the audience will have put all the pieces together before his character does. If you can forgive these flaws, then Sinister is surprisingly creepy and well worth a late night visit. The Score: 7/10

Next time: with the home stretch in site, I’ll be covering days seven and eight, with more scares, more giraffes and some micro-budget cinema.

Review: Looper

The Pitch: Witness to the future.

The Pitch: Witness to the future.

The Review: Is it possible to know that you’ll love a film before you even see it? If I look through the list of my favourite films, then certain types of films keep cropping up: action movies, thrillers, science fiction and in particular time travel movies. Despite their tricksy ways with time, everything from The Terminator movies to Twelve Monkeys has been a particular favourite of mine over the years, and Back To The Future still retains its place as my favourite film of all time. But it’s not just the possibilities of time travel that cast their spell over me, it’s the rich tapestry that each of these films uses time travel to weave, in each case skilfully combining different story elements into a compelling tale. But for each of those classics, there’s a Timecop or an A Sound Of Thunder. So does Looper have all of the required elements to add it to the classic list?

First, there’s the setting. Looper raises the bar on other time travel movies by having no passage set in contemporary times, and using that to derive its unique selling point. Think of most time travel movies and they consist of characters from our time travelling forwards or backwards in time, or vice versa. Looper is set entirely in the future, and predominantly in two different futuristic years; time travel, having been invented by 2074, allows the criminal underworld to dispose of their evidence by sending it back in time thirty years to 2044. Loopers are the clean-up crew of the relative past, instantly killing off the criminals of the future as they are sent back in time, then cleanly disposing of the evidence. They do this in the knowledge that one day, they’ll be the one on the mat facing them on the other end of the a giant gun, at which point the loop is closed, with a pay-off sent along to help the last thirty years of their life run smoothly. And heaven help anyone who doesn’t manage to close their loop when their future self comes visiting…

In addition to the entirely futuristic setting, it manages to be an entirely convincing futuristic setting, regardless of the time period, feeling both a natural extension of current times, but at the same time suitably lived in. Not since Minority Report have we seen such a well thought out and absolutely convincing future setting, with not a single detail feeling out of place. That feeling of reality is also down to the characters, who while feeling totally of their era have issues and problems which are universal, even if they are set up by time travel shenanigans. The biggest trick for any film set across two periods to pull off is a convincing pair of actors playing the same role at different times, especially when one of those actors has one of the most famous faces on the planet. But thanks to some convincing prosthetics and the power of the actors concerned, you will never doubt for one second that Joseph Gordon-Levitt is a young Bruce Willis; an impressive trick to pull off when they have so many scenes together.

Two things have elevated those other time travel movies to classic status: their mind and their soul. By their soul, I’m thinking of the tone of the story, the emotions that support the narrative, be it the comedy and romance of Back To The Future, the pulse-pounding threat of the Terminator or the poignant inevitability of Twelve Monkeys. Looper has a sense of humour, in keeping with director Rian Johnson’s previous films (Brick and The Brothers Bloom) but also an occasionally sick and sadistic touch, more darkly comic, revelling in the abilities of messing with characters who straddle two time periods. It also has soul, revealed in the second half of the movie which takes in a complete change of setting – and one which may prove to much of a right-angled turn for some audiences revelling in the futuristic nature of the backdrop to deal with – but one which allows the acting talents of Emily Blunt and young newcomer Pierce Gagnon to shine.

The other aspect is the mind, the high concept which instantly nails the story in your mind. What would you do if you went back in time and met your parents? Or if you were the mother of the future saviour of the human race, but spent your life hunted because of it? Looper’s hook seems to be initially whether you’d be able to kill your future self if the price is right, but in that Emily Blunt-based second half reveals itself to be something more basic and profound. The time travelling logic is as nebulous as that of many of its classic forebears (trying to make sense of timelines in most time travel movies will leave you scratching your head if you look too closely, and Looper actively plays with these expectations), but that shouldn’t detract from writer / director Johnson’s achievement; to create a time travel film which calls back in subtle ways to the greatness of its forebears, but also creates a unique vision with a mind and a soul all its own. I suspect people will still be talking about this one thirty years from now.

Why see it at the cinema: Movies like this are made for the big screen, and the sheer level of incidental detail in the background of the first hour needs to be seen as big as possible to truly appreciate, but it’s also best seen with an audience, as you’re bound to want to talk about it afterwards.

The Score: 10/10

Cambridge Film Festival Diary: Day 5

Day 5 of the festival, and this was the peak I was working to. Like a gym exercise bike attempting to mimic riding up and down a mountain, I’d started slow with days of three or four films, but the Monday of the festival was always destined to be the big day. If you’re at the festival morning, noon and night then each screen gets through typically six screenings or programmes in a day, so with some careful planning and no care for your own personal sanity, it is possible to squeeze in six films. That, on Monday, is precisely what I did.

Day 5 of the festival, and this was the peak I was working to. Like a gym exercise bike attempting to mimic riding up and down a mountain, I’d started slow with days of three or four films, but the Monday of the festival was always destined to be the big day. If you’re at the festival morning, noon and night then each screen gets through typically six screenings or programmes in a day, so with some careful planning and no care for your own personal sanity, it is possible to squeeze in six films. That, on Monday, is precisely what I did.

I’ve blogged before on the challenges of seeing seven films in a day, and the care that needs to be taken. Seeing six at a festival is a slightly different challenge, as choice is reduced and the planning made somewhat easier, but the logistics of taking in food – not to mention avoiding a DVT – still make it a challenge not to be entered into lightly. The real key is ensuring variety, and the selections I’d made, from Estonia to London (in two eras) via Germany and France, helped to prepare me for the day ahead.

These were the films I saw on Monday 17th September.

The Temptation Of St. Tony (Püha Tõnu kiusamine) Long time readers will know I’m not a fan of awards, as they get more right than they do wrong. Despite quite liking the Danish film In A Better World which won the Best Actor, there was already a long list from that year’s official submissions I liked more (Incendies, Of Gods And Men, Dogtooth, Confessions, Biutiful and Tirza, in case you were wondering), and that list has now gotten one longer. It’s also testament to the benefit of occasions such as the film festival, as this was showing in a short Estonian season, and as far as I can tell has never had a theatrical release in this country before.

The Temptation Of St. Tony (Püha Tõnu kiusamine) Long time readers will know I’m not a fan of awards, as they get more right than they do wrong. Despite quite liking the Danish film In A Better World which won the Best Actor, there was already a long list from that year’s official submissions I liked more (Incendies, Of Gods And Men, Dogtooth, Confessions, Biutiful and Tirza, in case you were wondering), and that list has now gotten one longer. It’s also testament to the benefit of occasions such as the film festival, as this was showing in a short Estonian season, and as far as I can tell has never had a theatrical release in this country before.

Given how few of the list of 66 submissions from that year have surfaced in this country, that can only be regarded as a crying shame, especially if Temptation is anything to go by. Divided into half a dozen separate chapters, but with overlapping narratives and characters, each explores facets of mortality as Tony reflects on life and existence. It starts as a black comedy and isn’t afraid to explore some darkly dramatic places as well, with some stunning and occasionally surreal images; the humour and the unique images will hook you in before director Veiko Õunpuu takes things up a notch, going to some deep, dark places on Tony’s journey of self-discovery. Taavi Eelmaa’s poised and often expressionless face marks his initially passive journey through events around him, becoming crucially more involved as he attempts to break away from and subvert his safe, domestic middle-aged existence. Look out also for an appearance from Denis Lavant, who stars in Holy Motors and which could also be a companion piece to this film. (Spoiler for day 11: I preferred this. I think. More on that later.) The Score: 9/10

Untouchable (Intouchables) It’s a French film, it’s already been a massive hit across the continent and it’s been picked up by the Weinsteins, and it currently sits at position number 73 on the Internet Movie Database’s list of the top 250 films of all time, as voted for by users. So what’s not to love? The story of a grumpy, frustrated quadriplegic who decides to shake up his life a little by hiring a Senegalese man just looking to meet the minimum requirements for his benefit claim, it’s a feel good film of epic proportions that isn’t afraid to have a laugh along with the characters at either their backgrounds or their afflictions, and there’s a huge amount of chemistry in the relationship between disabled but wealthy Phillippe (François Cluzet) and troubled but charismatic carer Driss (Omar Sy). Indeed, what’s not to love?

Untouchable (Intouchables) It’s a French film, it’s already been a massive hit across the continent and it’s been picked up by the Weinsteins, and it currently sits at position number 73 on the Internet Movie Database’s list of the top 250 films of all time, as voted for by users. So what’s not to love? The story of a grumpy, frustrated quadriplegic who decides to shake up his life a little by hiring a Senegalese man just looking to meet the minimum requirements for his benefit claim, it’s a feel good film of epic proportions that isn’t afraid to have a laugh along with the characters at either their backgrounds or their afflictions, and there’s a huge amount of chemistry in the relationship between disabled but wealthy Phillippe (François Cluzet) and troubled but charismatic carer Driss (Omar Sy). Indeed, what’s not to love?

Quite a lot, actually. If you approach the film with blinkers on, just looking at the relationship in isolation, it’s easy to see the charm and entertainment of the lead pairing, but as you cast your gaze wider the stereotypes and clichés stack up with an alarming frequency. Black man likes Seventies disco music but upper class white man is into classical music? Fair enough. Black man has a view that modern art is just squiggles on a paper and anyone can do it? Erm… White rich man has disaffected, troubled daughter (with boyfriend in tow), carer comes from a troubled background with disappointed mother and even more troubled siblings? White rich man also has a PA who’s the only one immune to the charms of his black carer, but she turns out to be a… I’ll let you guess; if you can’t, this may be the film for you, but it certainly wasn’t for me, the engineered storytelling (based on a true story, but with so many details put through the poor storytelling mangle that it always feels fake) and the inability to give any of the subplots the time they need simply because so many have been stacked up makes Untouchable start to feel top heavy and ultimately a rather cynical attempt to play on your emotions and engage your sympathies, almost an entertainment-seeking monster than an actual film. The Score: 5/10

The Big Eden It seems every country has one; a good time entrepreneur with a seedy image but charisma to burn and an almost inexplicable ability to charm the ladies. America have their Hugh Hefner, Britain their Peter Stringfellow and Germany their Rolf Eden. Eden came to notoriety through a set of Berlin nightclubs that he set up (and which all failed dramatically once he’d sold them off), and The Big Eden presents Rolf’s life story, interspersed with interviews from both his contemporaries and the many women he’s been with over the years. A number of those women have also produced children, and their stories help to add a contemporary perspective to a story that is, by nature, slightly rooted in the past. Other than the significant age range of the children he’s sired, The Big Eden is a little unremarkable, but it does succeed to an extent in getting underneath what’s made such a success of the man, and how he’s become so appealing to the ladies. The Score: 7/10

The Big Eden It seems every country has one; a good time entrepreneur with a seedy image but charisma to burn and an almost inexplicable ability to charm the ladies. America have their Hugh Hefner, Britain their Peter Stringfellow and Germany their Rolf Eden. Eden came to notoriety through a set of Berlin nightclubs that he set up (and which all failed dramatically once he’d sold them off), and The Big Eden presents Rolf’s life story, interspersed with interviews from both his contemporaries and the many women he’s been with over the years. A number of those women have also produced children, and their stories help to add a contemporary perspective to a story that is, by nature, slightly rooted in the past. Other than the significant age range of the children he’s sired, The Big Eden is a little unremarkable, but it does succeed to an extent in getting underneath what’s made such a success of the man, and how he’s become so appealing to the ladies. The Score: 7/10

The Lodger: A Story Of The London Fog Thanks to the BFI and their restoration efforts, a number of Alfred Hitchcock films have now been returned to cinemas looking better than ever, and the Cambridge Film Festival had a season of a dozen of the master’s top works, both from his rich Hollywood period and from his silent British days. The Lodger is one of those earlier films, but bears all of the hallmarks of his later work, not least in his willingness to corrupt the image of a screen idol of the time, in this case Ivor Novello as the shady traveller who takes room and lodgings at the same time that a serial killer named The Avenger is terrorising London every Tuesday. The methodical nature, the plot twists and the direct camera work are all present and correct and it clearly demonstrates that it wasn’t just in Hollywood and in colour that Hitch was able to work his magic.

The Lodger: A Story Of The London Fog Thanks to the BFI and their restoration efforts, a number of Alfred Hitchcock films have now been returned to cinemas looking better than ever, and the Cambridge Film Festival had a season of a dozen of the master’s top works, both from his rich Hollywood period and from his silent British days. The Lodger is one of those earlier films, but bears all of the hallmarks of his later work, not least in his willingness to corrupt the image of a screen idol of the time, in this case Ivor Novello as the shady traveller who takes room and lodgings at the same time that a serial killer named The Avenger is terrorising London every Tuesday. The methodical nature, the plot twists and the direct camera work are all present and correct and it clearly demonstrates that it wasn’t just in Hollywood and in colour that Hitch was able to work his magic.

The only slight downside about this particular print was the score by Nitin Sawhney, which while evocative of both mood and period for the most part, used a couple of more contemporary sounding songs which jarred slightly, but since they were out of the director’s control I’m willing to let him off this time. The Score: 8/10

Now Is Good The second film I’ve seen at the festival, after Come As You Are, to ostensibly feature a character or characters searching for sex as part of a wider purpose, Now Is Good isn’t really about that at all. Sex is just one of many narrative diversions that this story, based on Jenny Downham’s fiction novel “Before I Die”, takes along the road of trying to understand what life must be like for a teenager dying of leukaemia and whether or not she can encapsulate a lifetime of experiences into a few short months. Dakota Fanning plays the stricken teen Tessa, perfecting a cut-glass English accent (which does occasionally feel at odds with the very contemporary Brighton setting), and Jeremy “War Horse” Irvine is saddled with the unfortunate job of being the eventual object of her affections, which mainly consists of standing in the background of scenes, alternating between looking shocked, repulsed and a bit gorgeous.

Now Is Good The second film I’ve seen at the festival, after Come As You Are, to ostensibly feature a character or characters searching for sex as part of a wider purpose, Now Is Good isn’t really about that at all. Sex is just one of many narrative diversions that this story, based on Jenny Downham’s fiction novel “Before I Die”, takes along the road of trying to understand what life must be like for a teenager dying of leukaemia and whether or not she can encapsulate a lifetime of experiences into a few short months. Dakota Fanning plays the stricken teen Tessa, perfecting a cut-glass English accent (which does occasionally feel at odds with the very contemporary Brighton setting), and Jeremy “War Horse” Irvine is saddled with the unfortunate job of being the eventual object of her affections, which mainly consists of standing in the background of scenes, alternating between looking shocked, repulsed and a bit gorgeous.

Where Now Is Good really resonates is with the characters and performances of Tessa’s parents, played by Paddy Considine and Olivia Williams. Considine is the overly controlling father who is struggling to come to terms with the fact he’ll outlive his daughter, and Williams the estranged mother who’s doing her best to take apathy and incompetence to new levels. Without their performances, Now Is Good would be just another teen drama, and possibly a slightly exploitative one; with them it becomes a rounded drama, which will engage the emotions of anyone with half a heart. If you can put aside a poorly handled sub-plot involving Tessa’s best friend (a cheery Kaya Scodelario) then Now Is Good succeeds on its own terms, and any of a sensitive disposition should make sure they pack a couple of hankies for the last act. The Score: 7/10

The film was followed by a generally cheery and pleasant Q & A with star Jeremy Irvine and producer Peter Czernin. Ranging from insights into what it was like to act opposite Considine (apparently him waving a butter knife around at the breakfast table during a scene came across as particularly menacing) to the experience of a girl with leukaemia actually coming to set, which was apparently surprisingly life-affirming. It’s only a slight shame that more of Irvine’s genuine charm that came across in the flesh wasn’t captured in the film.

Tower Block A very British take on the high rise drama, it’s a simple set-up that tries its hardest to wring tension out of a set of generally unsympathetic and unlikeable characters. A murder takes place on the top floor of a tower block, but the residents are either too scared or too partisan to get involved with finding the culprit. The block is being evacuated by developers, and eventually those top floor residents are (conveniently) the last residents left in the building, all the easier to be picked off by a mystery sniper. The quality of the actors is good, with new British talent such as Sheridan Smith and Russell Tovey mixing with the likes of more established names of the likes of Ralph Brown and Julie Graham, but the only real standout in a coterie of people you wouldn’t want to live next to is Jack O’Connell as the protection money collector Kurtis, who makes unpleasantness an art form and is all the more watchable for it.

Tower Block A very British take on the high rise drama, it’s a simple set-up that tries its hardest to wring tension out of a set of generally unsympathetic and unlikeable characters. A murder takes place on the top floor of a tower block, but the residents are either too scared or too partisan to get involved with finding the culprit. The block is being evacuated by developers, and eventually those top floor residents are (conveniently) the last residents left in the building, all the easier to be picked off by a mystery sniper. The quality of the actors is good, with new British talent such as Sheridan Smith and Russell Tovey mixing with the likes of more established names of the likes of Ralph Brown and Julie Graham, but the only real standout in a coterie of people you wouldn’t want to live next to is Jack O’Connell as the protection money collector Kurtis, who makes unpleasantness an art form and is all the more watchable for it.

Directors James Nunn and Ronnie Thompson do what they can to wring tension from the situation and there’s some moody scenes, but genuine tension proves harder to come by. It’s not all their fault; while James Moran’s script does deal out a few good lines to O’Connell, Smith and Tovey, it’s a little pedestrian and often predictable, and doesn’t match up either to his work on the likes of Doctor Who and Torchwood, or indeed to his Danny Dyer-featuring horror Severance from 2005. This is one middling Brit thriller it’ll be hard to get stuck into. The Score: 6/10

Next time: sushi, suspicion, Sinister and some amazing Mongolian music in my not quite alliterative day 6.

Cambridge Film Festival Diary: Day 4

Sunday is supposedly a day of rest, but it’s also an ideal day for the cinema. Taking on something like the film festival requires a certain level of pacing if you’re going to see as much as I’ve planned to, so after two very full days on days 2 and 3 day 4 was the chance just to keep my hand in, before the big push over the next few days. Sunday morning’s normal routine was followed by Sunday lunch with Mrs Evangelist, eaten on our laps while attempting to keep up with Celebrity Masterchef. (Never let it be said I don’t know how to show a lady a good time.) Mrs E, as I refer to her on Twitter, is a more average film fan and is also a shift worker thanks to people rather inconsiderately being ill outside of office hours, so the festival is my chance to head off on my own and explore some of the more esoteric delights that cinema has to offer.

Sunday is supposedly a day of rest, but it’s also an ideal day for the cinema. Taking on something like the film festival requires a certain level of pacing if you’re going to see as much as I’ve planned to, so after two very full days on days 2 and 3 day 4 was the chance just to keep my hand in, before the big push over the next few days. Sunday morning’s normal routine was followed by Sunday lunch with Mrs Evangelist, eaten on our laps while attempting to keep up with Celebrity Masterchef. (Never let it be said I don’t know how to show a lady a good time.) Mrs E, as I refer to her on Twitter, is a more average film fan and is also a shift worker thanks to people rather inconsiderately being ill outside of office hours, so the festival is my chance to head off on my own and explore some of the more esoteric delights that cinema has to offer.

Sunday’s particular delights, then, were for fans of Jack Kerouac, Icelandic music and animals, but all in very specific ways.

On The Road This adaptation of the famous Kerouac novel has taken a ridiculous amount of time to come to screen, and in the process has been throug a number of different hands; it’s a shame to say that it doesn’t entirely appear to be worth all that effort. The director who finally brings this to the screen is Walter Salles, and he’s retained his gift for spectacular scenery and mind-searing visuals; what unfortunately is lacking, in both his direction and Jose Rivera’s screenplay, is the lyrical rhythm that has made On The Road so enduring as a work of fiction, and resorting to simply reading sequences of prose out at various points simply shows the gap in interest level between book and screen, the film version never quite managing to come truly alive.

On The Road This adaptation of the famous Kerouac novel has taken a ridiculous amount of time to come to screen, and in the process has been throug a number of different hands; it’s a shame to say that it doesn’t entirely appear to be worth all that effort. The director who finally brings this to the screen is Walter Salles, and he’s retained his gift for spectacular scenery and mind-searing visuals; what unfortunately is lacking, in both his direction and Jose Rivera’s screenplay, is the lyrical rhythm that has made On The Road so enduring as a work of fiction, and resorting to simply reading sequences of prose out at various points simply shows the gap in interest level between book and screen, the film version never quite managing to come truly alive.

Of the main cast members, the only one that stands out is Garrett Hedlund as the mischievous Moriarty; Sam Riley is a good actor in search of the right role, being as fundamentally miscast here as he was in last year’s Brighton Rock. It’s the supporting turns from the likes of Viggo Mortensen that will live longest in the memory, and while Kristen Stewart has a certain amount of fizz, she gets very little to do. On The Road very much conforms to the stereotype of Stewart’s contemporaries, great to look at but with little of substance on the inside. The Score: 6/10

Grandma Lo-Fi (Amma Lo-Fi) The story of an Icelandic woman in her Seventies who turned her hand to making music with a small keyboard and a variety of household sounds, Grandma Lo-Fi is small but almost perfectly formed, capturing completely the charm and eccentricity of Sigridur Nielsdottir, but also what has made her music so appealing to many. Detailing her background and her approach to her music, right through to the delightful cover art she produces for the CDs she has pressed herself, it’s an inspiration as to what can be achieved through the simple process of application. Despite the short running time, there are a few odd kinks in the tail, but if you’re looking for a documentary to give you a warm glow, Grandma Lo-Fi should suffice, another entry into what is currently proving a stand-out year for music documentaries. The Score: 8/10

Grandma Lo-Fi (Amma Lo-Fi) The story of an Icelandic woman in her Seventies who turned her hand to making music with a small keyboard and a variety of household sounds, Grandma Lo-Fi is small but almost perfectly formed, capturing completely the charm and eccentricity of Sigridur Nielsdottir, but also what has made her music so appealing to many. Detailing her background and her approach to her music, right through to the delightful cover art she produces for the CDs she has pressed herself, it’s an inspiration as to what can be achieved through the simple process of application. Despite the short running time, there are a few odd kinks in the tail, but if you’re looking for a documentary to give you a warm glow, Grandma Lo-Fi should suffice, another entry into what is currently proving a stand-out year for music documentaries. The Score: 8/10

Postcards From The Zoo (Kebun binatang) Finally for day 4, a fairy tale of sorts, set in and around Jakarta Zoo in the Indonesian capital. It’s the story of a young girl, Lana, who grows up in the zoo and dreams of being able to touch the belly of the giraffe, frustratingly out of reach for many reasons. The story draws parallels with the conservation of wildlife and the issues facing endangered species in Lana’s journey through the zoo and into the city beyond in the company of a magical cowboy. However, what may sound on the page as a story book piece comes across on the screen as flat and uninspired, none of the various story elements really gelling and the characters just not working. It’s a brave attempt and is willing to explore plenty of facets of life in the Indonesian big city; it’s just a shame that it couldn’t find any to truly engage with. The Score: 5/10

Postcards From The Zoo (Kebun binatang) Finally for day 4, a fairy tale of sorts, set in and around Jakarta Zoo in the Indonesian capital. It’s the story of a young girl, Lana, who grows up in the zoo and dreams of being able to touch the belly of the giraffe, frustratingly out of reach for many reasons. The story draws parallels with the conservation of wildlife and the issues facing endangered species in Lana’s journey through the zoo and into the city beyond in the company of a magical cowboy. However, what may sound on the page as a story book piece comes across on the screen as flat and uninspired, none of the various story elements really gelling and the characters just not working. It’s a brave attempt and is willing to explore plenty of facets of life in the Indonesian big city; it’s just a shame that it couldn’t find any to truly engage with. The Score: 5/10

Quote of the day: “Marylou, spread your knees and let’s smoke some weed!” – Dean Moriarty, On The Road

Health update: More walking, mainly to work off the pizza and, ahem, chocolate cake I had for dinner. Just starting to get slightly sore knees. Being tall is not all it’s cracked up to be when it comes to small cinema seats. Only another week to go.

Next time: Day 5, thanks to the unstinting passage of time, and my busiest day of the festival, from Estonian mortality drama to British horror with just about everything in between.

Cambridge Film Festival Diary: Day 3

The first Saturday of the festival, and one where I normally don’t get to see much as I have another tradition I’ve followed since moving to the area. I do sometimes worry that people misunderstand the “Evangelist” in the name of the blog, as the only religion here is films, and no gods to speak of (but a bit of Christopher Nolan worshipping occasionally). Outside the blog, as long time readers will probably remember, I do a lot of other things, including being choir master of my village church; this gives me the opportunity each September to join a service where choirs from all over Cambridge meet to sing in King’s College chapel. As strong as my love of film is, chances like this don’t come along every day (about once a year, in fact), so the first Saturday is traditionally a thin day for me in terms of films.

The first Saturday of the festival, and one where I normally don’t get to see much as I have another tradition I’ve followed since moving to the area. I do sometimes worry that people misunderstand the “Evangelist” in the name of the blog, as the only religion here is films, and no gods to speak of (but a bit of Christopher Nolan worshipping occasionally). Outside the blog, as long time readers will probably remember, I do a lot of other things, including being choir master of my village church; this gives me the opportunity each September to join a service where choirs from all over Cambridge meet to sing in King’s College chapel. As strong as my love of film is, chances like this don’t come along every day (about once a year, in fact), so the first Saturday is traditionally a thin day for me in terms of films.

Having studied the diary very carefully this year I’d determined I could manage to squeeze in three films, one before the afternoon rehearsal and two after the wrap up at King’s. But because I obviously wasn’t busy enough, when Toby Miller from Cambridge 105’s film review show Bums On Seats had seen on Twitter that I’d seen Come As You Are, I took up the offer to join the show to share my 2p worth. There was also a discussion on Hope Springs, which I’d seen (and seemingly enjoyed slightly more than my fellow reviews, although not much). All seemed simple enough and ideally set to fit into my schedul; at the studio for 10:30, bit of prep and discussion and then on air from 11:00 to 12:00.

I knew roughly where the studio was, but thankfully I’d got two separate sat navs just in case. They both lie. Actually, that’s a little unfair to them; they’re old and unsophisticated, so unlike many modern sat navs they don’t tell you what extra time you’ll need to get through traffic, and Saturday morning traffic in Cambridge, which they both sent me straight into the middle of, seemed particularly testing. Having been four minutes away for about half an hour, I finally arrived at the studio at around 10:50 in a mild state of panic. Thankfully I was in time for the show, but what I’d been denied was the opportunity to see what was coming.

This is my excuse, anyway, for the ramblings which I’ve just listened back to on the podcast; suddenly having to have articulate thoughts and express them coherently, rather than the opportunity to edit and re-edit what I’ve written until I don’t sound like a raving madman. Having re-read the first paragraphs of this, I’ve realised that no amount of time will stop me sounding like a madman, so if the opportunity arises again I will try to be a little less self-conscious. Anyway, don’t take my word for it, here’s the chance to hear what I had to say (if you’re quick), and to sigh, tut and to disagre with it strongly. Thanks again to Toby for the opportunity, and to my fellow reviewers for allowing me to help them sound good.

After all that, I still got those three films in, and here’s what I saw on Saturday 15th September.

Hemel Hemel translates as “heaven”, which might seem an odd name for a daughter, especially one who’s grown up as cantankerous and rebellious as Heaven has. She has a close relationship with her father, and Hemel explores that relationship as well as their respective attempts to find love. What Hemel actually finds more of is sex; the film is a series of vignettes focusing on either a new man in Heaven’s life or a new woman in her father’s. The copious nudity and frank, sometimes brutal, reality of the feelings expressed by the Hemel family might be offputting to some but Hemel is very good at getting underneath the nature of relationships and succeeds in maing the characters sympathetic rather than alientating, while still allowing father and daughter to get off a succesion of stinging barbs at each other. It does find real emotion, especially in Hannah Hoekstra’s central performance, and while there’s nothing hugely earth-shattering or revelatory Hemel does satisfy on its own brief terms. The Score: 7/10

Hemel Hemel translates as “heaven”, which might seem an odd name for a daughter, especially one who’s grown up as cantankerous and rebellious as Heaven has. She has a close relationship with her father, and Hemel explores that relationship as well as their respective attempts to find love. What Hemel actually finds more of is sex; the film is a series of vignettes focusing on either a new man in Heaven’s life or a new woman in her father’s. The copious nudity and frank, sometimes brutal, reality of the feelings expressed by the Hemel family might be offputting to some but Hemel is very good at getting underneath the nature of relationships and succeeds in maing the characters sympathetic rather than alientating, while still allowing father and daughter to get off a succesion of stinging barbs at each other. It does find real emotion, especially in Hannah Hoekstra’s central performance, and while there’s nothing hugely earth-shattering or revelatory Hemel does satisfy on its own brief terms. The Score: 7/10

V.O.S. (Original Subtitled Version) Described by those people who like to use other similar things to describe things as Charlie Kaufman-esque, V.O.S. played in the Calatan cinema stream at the festival, and Cesc Gay’s film takes the relationships of two couples and places them within a film-within-a-film setting. We’re never quite sure if we’re watching them making the film or them actually being the characters, with one of them writing a script which details the lives of the characters, and so on, and so forth. While there’s some clever touches and the conceit is maintained throughout, it doesn’t quite have the clarity of purpose of Kaufman’s better work and is also fairly bog-standard in terms of the relationships on display, lacking credibility at a couple of key junctures. But maybe we should blame that on the writer? Or maybe on the character of the writer? The Score: 6/10

V.O.S. (Original Subtitled Version) Described by those people who like to use other similar things to describe things as Charlie Kaufman-esque, V.O.S. played in the Calatan cinema stream at the festival, and Cesc Gay’s film takes the relationships of two couples and places them within a film-within-a-film setting. We’re never quite sure if we’re watching them making the film or them actually being the characters, with one of them writing a script which details the lives of the characters, and so on, and so forth. While there’s some clever touches and the conceit is maintained throughout, it doesn’t quite have the clarity of purpose of Kaufman’s better work and is also fairly bog-standard in terms of the relationships on display, lacking credibility at a couple of key junctures. But maybe we should blame that on the writer? Or maybe on the character of the writer? The Score: 6/10

Dead Before Dawn 3D Writer Tim Doiron and director April Mullen are on the verge of becoming Canadian institutions at the Cambridge Film Festival. Having been in 2009 with Rock, Paper, Scissors: The Way Of The Tosser and a year later with Gravytrain, they were back (sadly not this time in person) with their third film, and where Gravytrain had been a spoof of hard-boiled crime fiction, this time the target was zombie and horror flicks. A group of dysfunctional college students manage to afflict themself with a rather unfortunate (and also rather unfortunately specific) curse which will become permanent upon sunrise. DBD3D succeeds rather more than Gravytrain did, not least for the fact that more of the scattergun humour actually works and there’s enough genre staples, as well as the odd piece of genre skewering, to help the film get by on its own good will and energy. Employing an impressive number of family members to give the movie a look bigger than its budget, there’s also a trump card in the form of a typically energtic performance from Christopher Lloyd. It’s not going to give the best examples of the genre any trouble, but you could do much worse for a few laughs on a Saturday night. The Score: 6/10

Dead Before Dawn 3D Writer Tim Doiron and director April Mullen are on the verge of becoming Canadian institutions at the Cambridge Film Festival. Having been in 2009 with Rock, Paper, Scissors: The Way Of The Tosser and a year later with Gravytrain, they were back (sadly not this time in person) with their third film, and where Gravytrain had been a spoof of hard-boiled crime fiction, this time the target was zombie and horror flicks. A group of dysfunctional college students manage to afflict themself with a rather unfortunate (and also rather unfortunately specific) curse which will become permanent upon sunrise. DBD3D succeeds rather more than Gravytrain did, not least for the fact that more of the scattergun humour actually works and there’s enough genre staples, as well as the odd piece of genre skewering, to help the film get by on its own good will and energy. Employing an impressive number of family members to give the movie a look bigger than its budget, there’s also a trump card in the form of a typically energtic performance from Christopher Lloyd. It’s not going to give the best examples of the genre any trouble, but you could do much worse for a few laughs on a Saturday night. The Score: 6/10

Mullen and Doiron weren’t able to be in the room, but they did dial in via Skype for a Q & A, with the audience (or what was left of it, as we were already well past midnight at this point) staying to ask affectionate questions. In particular, Mullen’s enthusiastic response to my question about a particular Christopher Lloyd moment – you’ll absolutely know the one when you see it – means I may now have just a tiny crush on the Canadian director. (And that was even before she promised to turn up in person in a cheerleader outfit at a future screening. Yikes.)

Quote of the day: “The beees! Aaargh! It’s always the bees!” – Dead Before Dawn 3D

Health update: A reasonably healthy lunch was offset by a slightly less reasonably healthy burger and chips in the Picturehouse bar. Plenty of walking to and from just about everywhere, and I might just about have gotten away with it.

Next time: Day 4, and it’s Kristen Stewart, an Icelandic musical granny and a girl with a disturbing giraffe fixation.

Cambridge Film Festival Diary: Day 2

Day two, the first full day of the festival. By now you’d expect me to be organised, but the sheer volume of my bookings was already working against me. As with the previous two years, I’d arrived for the first film and then all of my tickets had printed out, a long stream like some form of Wall Street ticker tape warning of impending crisis. My crisis came from the fact that, as always, the tickets don’t seem to print off in any particular order; so on day one I had a long stream of 36 tickets from the main booking, and by day two that was four still fairly long streams where I’d taken the previous days’ tickets out of the middle. The sight of me performing what must have looked like the world’s least interesting magic trick I hope at least kept the staff of the Picturehouse entertained.

Anyway, onto the day itself: this was Friday 14th September 2012.

The day started with a repeat screening of one of the previous night’s opening films. Hope Springs is the tale of a couple in their 31st year of marriage, where Tommy Lee Jones is content to follow the same predictable, pedestrian routine but Meryl Streep yearns to put some spark back into their marriage. A good proportion of the film is either a two-hander with Jones and Streep formulating their issues, or a three-way with Steve Carell (less exciting than it sounds, I can assure you) as the therapist looking to work through their issues for them.

I certainly wouldn’t devalue the idea of couples therapy as such, but the film never convinces in terms of the therapy itself, feeling far too superficial to really get at the deep roots of the couple’s problems. In terms of entertainment value it’s a moderate success; Streep can normally be relied upon to be a class act, but she comes across as slightly mannered here, and Carell is required to simply turn up and be as calm as possible while keeping a straight face while saying words like “masturbate” or “penis”. Most of the joy comes from watching Tommy Lee Jones be a spectacular grump for as long as possible, which also makes his character slightly unsympathetic. Recommended if you’ve been married a while and can’t afford $4,000 dollars for counselling, although I would suggest avoiding a repeat of what Streep and Jones get up to in their movie theatre visit. The Score: 6/10

Scandinavian art cinema takes a step backwards in the form of this mercifully short study of the trials and tribulations of nightclub promoter Janne (Johannes Brost). Enjoying life without complete regard for others, an unfortunate accident leaves him with a number of problems on his hands, but neither he nor the film are interested in getting anywhere near solving those problems. A dark film offering little hope for any of its characters, lifelessly shot it’s only the weathered performance of Brost that’s likely to keep you invested. Don’t expect to see a huge return on that investment. The Score: 4/10

I was going to start this paragraph with “harrowing”, but I’m not sure that any words come close to capturing the dehumanising brutality that Shin Dong-Hyuk had to endure growing up in a North Korean labour camp. While there’s a small element of talking heads from other participants who’ve also escaped the North’s regime, the majority of the film is based around Shin’s reflections on his experiences and his attempts to cope with life in a more civilised world. His memories of the camp are captured in some part in animation, with a Schindler’s List colour palette giving way to an understated animation style that worked so well for Waltz With Bashir a couple of years ago, but the most powerful sequences are actually set in Shin’s flat, his silences and difficulties in recalling his experience making the viewer uncomfortably complicit in asking him to review this. A heartbreaking sense of a life almost irredeemably lost isn’t totally well served by the structure, and a better edit could take this up by a point or even two, but it’s still a deeply affecting portrayal of the human spirit and its attempts to overcome adversity. The Score: 8/10

Germany’s entry for the 2012 Academy Awards Best Foreign Language Film is another tale exploring life in the divided Germany of post war years, in this case a tale of two doctors in a small country hospital in East Germany. Barbara (Nina Hoss) is under close scrutiny in her relocation, and for good reason given that she has a number of secrets she’s trying to hide; André (Ronald Zehrfeld) has different reasons for being there, but both are working through their own lives while trying to do their best for the succession of young patients coming through their doors. Zehrfeld has charisma to burn and nicely offsets Hoss’s colder, but still sympathetic, performance. Director Christian Petzold tells his tale in a measured fashion, but doesn’t quite succeed in generating tension where all of the possibilities present themselves; it’s still a well fashioned story, kept alive by the performances of its two leads. The Score: 7/10

And so to Tridentfest, the collection of short films and music videos that has claimed the first Friday night of the festival for the past few years. If you’ve never been, then it’s a collection of very local film makers (often filming in their own houses or the Picturehouse bar) exploring different facets of film making, sometimes thoughtful, occasionally gory, but almost always very funny.

This year there was nothing to match last year’s The Purple Fiend for length (the longest film clocking in at barely 10 minutes), but variety is the spice of life and we certainly got that again this year. Highlights for me were some of the music videos, especially one to a song from British Public (I think) which seemed to have a chorus consisting of chanting “bears” over and over again – which, unsurprisingly, stuck in my head for days – and Chess Man, a real life insight into a man who plays lots of chess and makes the occasional piece of artwork, much of it shot on VHS-C tapes acquired off the internet.

But it’s the eccentricity, the laughs and the just plain down right oddness that make Tridentfest so memorable; from Teaching Simon To Skate, mixing a sense of British sporting endeavour into some Jackass-like skateboarding pain, to Andy Needs His Milk, an utterly disturbing but memorable tale of a disembodied but demanding head. The evening was rounded off with one of the many shorts from The Fantastic Poo Brothers, called Powers; it might be one of the most pointlessly stupid things I’ve ever seen, but four days later I’m still smiling when I think about it. That is the quite literal joy of Tridentfest, and hopefully a second screening later in the week will give you chance to see what you may have missed.

The evening was rounded off with a chat with a couple of the members of the Project Trident team, which brought to light the fact that the poster in the foyer for Tridentfest bears a poster quote from my review of The Purple Fiend last year, as indeed does the DVD case, which they were kind enough to give me a copy of. Possibly my greatest achievement as a blogger to date. Possibly as a human being. (Sorry, I don’t get out much.)

Next time: Day 3, featuring Hemel, V.O.S., Dead Before Dawn 3D and how traffic nearly killed the radio star before he even got started.

Cambridge Film Festival Diary: Day 1

One of the highlights of my year for the past two years since I started this blog, the Cambridge Film Festival kicked off again this week. For my third year at the festival, thought I’d try something a little different, given that the rate at which I manage to review films makes me the Geoffrey Boycott of blogging. (I promise not to state that my grandmother could have directed that better or that even a stick of rhubarb could have out-acted Kristen Stewart, as Mr Boycott invariably would.) So this year, I’ll be picking up more of a diary feel, which means I can at least give an opinion on everything, not just the feature films, and also share my experiences of the festival when I’m not sat in front of a cinema screen. (I would expect me to be sat mainly in the bar, although there’s already been a few other highlights.)

One of the highlights of my year for the past two years since I started this blog, the Cambridge Film Festival kicked off again this week. For my third year at the festival, thought I’d try something a little different, given that the rate at which I manage to review films makes me the Geoffrey Boycott of blogging. (I promise not to state that my grandmother could have directed that better or that even a stick of rhubarb could have out-acted Kristen Stewart, as Mr Boycott invariably would.) So this year, I’ll be picking up more of a diary feel, which means I can at least give an opinion on everything, not just the feature films, and also share my experiences of the festival when I’m not sat in front of a cinema screen. (I would expect me to be sat mainly in the bar, although there’s already been a few other highlights.)

So here’s my rundown of day 1, Thursday 13th September 2012.

About Elly The first film I’ve seen at the festival in the past two years was a 10/10 both times, and ended up in my top 10 of the year (Winter’s Bone and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy respectively, thank you for asking). While gratifying to see an outstanding film first up, it then leaves the problem that everything coming after it proves to be anticlimactic. About Elly neatly sidestepped that problem for me by just being great.

About Elly The first film I’ve seen at the festival in the past two years was a 10/10 both times, and ended up in my top 10 of the year (Winter’s Bone and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy respectively, thank you for asking). While gratifying to see an outstanding film first up, it then leaves the problem that everything coming after it proves to be anticlimactic. About Elly neatly sidestepped that problem for me by just being great.

Actually the film before A Separation, Asghar Farhadi has now two definite pieces of work to show his ability to blend compelling narratives with suspense, to shade his characters rather than casting them as completely black or white and to be able to comfortably mix Iranian social issues with a more general backdrop. For the first half, About Elly could be set on a beach just about anywhere but events unfold in such a way that social pressures and gender issues help to shape the drama but to keep it accessible.

The story of a beach trip with turns to near tragedy and then an unfolding mystery, Farhadi keeps his characters grounded and believable and it’s to the credit of all involved that I genuinely couldn’t predict the outcome. Without being outlandish, there’s enough subtle twists and revelations of motives to keep you hooked throughout. Following in the footsteps of the likes of Abbas Kiarostami and Jafar Panadi, Farhadi is part of a strong generation of Iranian film makers, and About Elly and A Separation put Farhadi at the forefront of that group. The Score: 8/10

Come As You Are (Hasta La Vista) Thanks to the Paralympics this summer, issues of disability and equal rights have been at the forefront of the minds of the nation, so this Flemish import may be arriving at just the right time. Loosely inspired by the experiences of Asta Philpot, three Flemish youths of varying degrees of disability have decided that they can no longer face the prospect of a lifetime of struggling to lose their virginity, and on hearing of a brothel in Spain that caters for those with similar conditions they determine to set off on a road trip, which goes about as well as road trips in comedies generally do, except with more jokes about disabilities.

Come As You Are (Hasta La Vista) Thanks to the Paralympics this summer, issues of disability and equal rights have been at the forefront of the minds of the nation, so this Flemish import may be arriving at just the right time. Loosely inspired by the experiences of Asta Philpot, three Flemish youths of varying degrees of disability have decided that they can no longer face the prospect of a lifetime of struggling to lose their virginity, and on hearing of a brothel in Spain that caters for those with similar conditions they determine to set off on a road trip, which goes about as well as road trips in comedies generally do, except with more jokes about disabilities.

During the Paralympics, certain tweeting comedians caused a furore by some of their humour, drawing a clear line where jokes should be fearful of crossing. Hasta La Vista understands this line well and always invites you to laugh with, never at, its participants when it comes to their disabilities, but to laugh at them for the same human fallibilities shared by everyone, whether disabled or not. The idea of heading to a brothel certainly won’t generate sympathy with everyone, but the plight and frustrations of these three lovable losers will keep you consistently entertained. A fantasy sequence near the end, intended to illustrate the liberation of the characters as they near the fulfilment of their quest, may actually cause you to question the reality of what you’ve watched and the ending feels a little pat while also leaving threads unresolved, but Hasta La Vista is still a journey well worth taking. The Score: 7/10

The Snows Of Kilimanjaro (Les Neiges Du Kilimandjaro)Robert Guédiguian has been to the Cambridge Film Festival before, and this time returns with a film inspired by a Victor Hugo poem, La Légende des siècles (The Legend of the Centuries). Set in and around a French shipyard town, Jean-Pierre Darroussin plays Michel, a French trade union representative whose show of solidarity in entering his name into a redundancy lottery at the shipyard sees him made redundant along with nineteen others. The film explores the ramifications on both Michel and his family and friends, but also on another of the nineteen, Christophe (Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet), who is attempting to raise his two younger brothers in the absence of their work-away mother.

The Snows Of Kilimanjaro (Les Neiges Du Kilimandjaro)Robert Guédiguian has been to the Cambridge Film Festival before, and this time returns with a film inspired by a Victor Hugo poem, La Légende des siècles (The Legend of the Centuries). Set in and around a French shipyard town, Jean-Pierre Darroussin plays Michel, a French trade union representative whose show of solidarity in entering his name into a redundancy lottery at the shipyard sees him made redundant along with nineteen others. The film explores the ramifications on both Michel and his family and friends, but also on another of the nineteen, Christophe (Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet), who is attempting to raise his two younger brothers in the absence of their work-away mother.

Guédiguian is keep to explore the social ramifications of the decision, reflecting the current economic climate more sharply than even when the film was first shown at Cannes last year, but this makes for a slightly uneasy marriage of political discourse and family drama. Views of the characters are kept broad, but somehow the film never quite gets truly to the root of some of their motivations, and the eventual resolution to the plot strains credibility somewhat. Still, the performances of the whole cast are generally strong and evoke a suitable amount of empathy, but Snows may not last in the memory for as long as the recession might. The Score: 6/10

The film was followed by a Q & A session with Guédiguian, who spoke through the use of an interpreter, feeling that he could more correctly convey his answers in French than in English. I studied French for five years at school and a further year at uni, and can often follow decent chunks of French films without reading all of the subtitles, but confronted with an actual fluent French speaker discussing the finer elements of his film left me feeling the need to scurry back to my worn copy of Tricolore from school and do some urgent revision. Guédiguian was a delight, though, charming and erudite and fielding a long procession of questions in both French and English.

In summary:

Film of the day: About Elly

Quote of the day: “F*** Ryanair!” – various characters, Come As You Are

Festival stamina: I should explain; I’m trying to lose three stone at present, put on by poor eating due to a busy work life, and am trying to maintain that over the course of the festival, in addition to regular exercise. Hopefully this diary will help me to keep track of how that’s going. Day 1 was a firecracker chicken at the nearby Wagamama, and was suitably filling and low calorie. I also got around forty minutes’ walking in two and from my car, so energy levels remain high one day in.

Coming on day 2: Hope Springs, Avalon, Camp 14: Total Control Zone, Barbara and Tridentfest 2012.

Cambridge Film Festival Review: Contagion

The Pitch: Outbreak 2: Infectious Boogaloo.

The Pitch: Outbreak 2: Infectious Boogaloo.

The Review: Fear of infections is a fairly modern phenomena. While great crime dramas or romantic comedies have been the subject of movies for decades, our fear of disease in our anti-bacterial, post-MRSA world is only now really starting to provide fodder for the great and the good of Hollywood. (Maybe that great unmade Black Death movie is still out there somewhere). But after three decades of disaster movies laying waste to everything in sight, audiences expect certain things from their movies, and in those respects Steven Soderbergh’s latest delivers – up to a point.

In any disaster movie, the first thing you want to see is a high class array of talent being put in jeopardy. If there’s one thing Soderbergh does well, it’s put a cast together, and he’s obviously given the Filofax a good thumbing before the cameras rolled. As soon as the credits roll, Gwynneth Paltrow appears on screen and she’s the first in a long succession of famous and familiar faces who appear, then start coughing and looking a bit pasty and sweaty. It would take most of this review to list the ones who do well, although Paltrow does get killed off before she has chance to do any damage, but by and large the acting falls into two categories: being asked to cough and splutter before an inevitable bout of death (or, in the case of Matt Damon, standing around while other people do that), or to stand in a room looking at computer screens or a conference table surrounded by stern looking, smartly dressed men while delivering reams of medical exposition about infection rates and worst case scenarios, and everyone does that as well as you’d expect.

The alternating between coughing and general sternness is edited together at a fair lick. Regular Soderbergh contributor and Oscar winner Stephen Mirrione never lets the pace flag, with scenes finely trimmed and the scenario and the constant threat being used to generate mood. The mood itself is very tense, starting uneasily and steadily building as events escalate and the authorities struggle to keep pace with the spread of the infection. If anything, it feels a little too trimmed, and occasionally scenes that need time to breathe or resonate get lost a little as the general pace sweeps along everything in its path. The other obstacle that Contagion has to overcome is Jude Law, who appears to have been taking lessons at the “Physical Impairment and Dodgy Accent” school of acting, his performance consisting of a dodgy tooth and a dodgier accent. If you manage to work out whether his accent is Australian or Cockney, please do let me know.

Contagion has a lot it’s trying to say, about the potential of such a situation, and of how everyone from governments to pharmaceutical companies would react in such a scenario. Consequently it’s not surprise that the pacy editing and the huge number of different narrative threads mean that a few ideas feel a little underdeveloped; some characters disappear for long stretches, and their reappearance often leaves you wondering what they’ve been up to in the interim. The overriding feeling is one of frustration, as while what’s here is great, and will give you chills every time the person next to you starts scratching their head, Contagion feels as if it would have been more effective as a six hour miniseries than the hour and forty-five minutes that is actually presented. The final disappointment comes in the ending, as it feels as if a few punches have been pulled and we get to see an ending that’s already been spelled out in the exposition earlier, like a whodunnit where a signed confession is found halfway through but everyone keeps investigating, just in case. Still, Contagion will get under your skin, even if it won’t leave a lasting impression.

Why see it at the cinema: The crisp digital visuals are definitely best suited to the cinema, but the USP of Contagion is that your paranoia will increase markedly as soon as someone on the other side of the cinema starts coughing. You just don’t get that at home.

The Score: 7/10

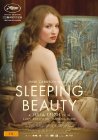

Cambridge Film Festival Review: Sleeping Beauty

The Pitch: The Jobbing Student’s New Clothes.

The Pitch: The Jobbing Student’s New Clothes.

The Review: Being a student isn’t easy – I had enough attempts at it to know. I certainly don’t envy those entering higher education in this country at present, for while I still had some form of grant to accompany my student loan, today’s undergraduates in the UK are likely to have £20-30,000 of debt by the time they get their degrees. I gathered, as Wayne Campbell once put it, “an extensive collection of nametags and hairnets” while working my way through university, even working on the bins at one point, and that was far from the worst student job I undertook. Julia Leigh’s new film, however, takes the student necessity for income as a jumping off point for an exploration of adult themes, of sexuality and relationships and exploitation.

Emily Browning is Lucy, the student at the centre of the film. When we first see her she’s having a tube fed down her throat as part of a medical experiment, gagging and retching as it’s fed down inside her, but it’s also contrasted with her variety of other jobs, from office work to waitressing. Despite the variety of work she’s doing, she’s struggling to pay the bills, so takes up an advert for silver service work of a unique nature. The change in her income has the potential to revolutionise her life, but her new role also offers the possibility of promotion, and with it a decision on whether to further compromise her morals in search of security.

While the films shares a title with Perrault’s original fairy tale, the narrative theme feels less like that or the Brothers Grimm version and more akin to Alice In Wonderland, as a girl is drawn into a strange and eclectic cast of characters and allows herself to be drawn into events. Much of the drawing is done by Rachael Blake’s Clara, the icy madam who draws Lucy increasingly into this uncomfortable world. But Lucy is a willing participant, driven by greed as much as need, and the film tries to say as much about the culture of youth and poverty as it does about the sexual mores and deviance of society in general. I have to emphasise the use of the words “tries to”, because Sleeping Beauty fails by varying degrees to achieve pretty much everything it sets out to. This is partly both because of and despite Browning, who is willing to invest herself in both the naked physicality and bare psyche of her character, but only succeeds in making that character so dislikeable as to put unintentional barriers between herself and the audience.

Most of the fault, though, must lie with Leigh. It’s possible to see what she intended, and various influences can be detected, but sadly there’s a much better film in the material than the one that Leigh has committed to film. The director instructed her lead to watch Charlotte Gainsbourg’s performance in Lars Von Trier’s Antichrist, but Leigh lacks the vision and talent for imagery that Von Trier so repeatedly manages. The themes of sexual exploration feel as if they could have been better handled by the likes of David Cronenberg; the movie attempts surreal imagery and situations, but dialogue and scenes (especially in Lucy’s one attempt at a genuine relationship with another person) come across as arch and stilted, and somehow the Lynchian feel that could have enhanced serves only to confuse; and the movie’s biggest waste of potential is in the scenes with Clara, both in her introductions and later on in the bedroom. It feels, particularly with the staging of long, uncut scenes pointed directly at the audience, as if this is Michael Haneke’s attempt at a pshcyosexual drama, but where Haneke has such flair for making his audience complicit in events or engaging their minds, Sleeping Beauty feels all gloss and no substance, as if the subtext got lost in the post somewhere between shooting and the cinema. It’s frustrating because it feels that any of those more established names might have gotten more out of these ideas, but Sleeping Beauty will do its best to alienate you from its themes, and gets lost in a wash of over-structured visuals and muddled messages, from its unfocused beginning to its anti-climactic and unsatisfying ending.